by P. Sreenivasulu Reddy

In the 1920s and 1930s Gandhi was not yet an undisputed leader. There were many who did not have faith in his nonviolent, non-cooperation movement. But his social reforms, such as eradication of untouchability, the picketing of hot toddy shops, and the social reform ideals influenced by Ruskin (sarvodaya) drew nearly everyone’s attention. The most humiliated and long neglected sections of Indian society had at last found someone to champion their cause, and by the late 1930s, Gandhi’s successful Salt Satyagraha campaign and march demonstrated to the world the effectiveness of the nonviolent struggle for independence. Apart from nonviolence (ahimsa), Gandhi’s love of truth and spirit of sacrifice made him the guiding spirit of the Indian freedom struggle. Under his influence, many sacrificed what little they had for the sake of making India a free country.

R. K. Narayan. Cover photo of Penguin Classics Edition

This article gives an overview of some appearances of Gandhi as a figure in Indian English-language fiction, for example as a character in Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable (1935), The Sword and the Sickle (1942) and Little Plays of Mahatma Gandhi (1991), and by other authors such as K.A. Abbas in Inqilab (1955), R.K. Narayan in Waiting for the Mahatma (1955), and The Vendor of Sweets (1967), and Nagarajan in Chronicles of Kedaram (1961).

Although he does not appear as a character in K.S. Venkataramani’s Murugan, the Tiller (1927) or Kandan, the Patriot (1932) nor in Raja Rao’s Kanthapura (1938), Gandhi is nonetheless the driving force represented by characters inspired by his ideals. Gandhi’s followers, if not Gandhi, also appear in Bhabani Bhattacharya’s So Many Hungers (1947), Mrs. Sahgal’s A Time to be Happy (1957) and the previously mentioned The Vendor of Sweets by R. K. Narayan.

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

The combination of humility and militancy in emotionally charged social conflicts has always been rare. It is easy to succumb either to passivity or to verbal or nonverbal violence. Humility in confronting a human being, respect for the status of being a human being, whether that being is a torturer or a holy person, is essential.

People may be trained in nonviolent communication through sessions where they confront others with different attitudes and opinions. In schools and universities such sessions in the form of seminars, or otherwise, are easy to schedule. At the university level proposals of norms or principles of nonviolent communication help students to master conflict situations. From 1941 to around 1993, the set of principles formulated in this article has been used by about ninety thousand working in small groups at Norwegian universities. An emotionally charged topic is often selected, and the students asked to discuss it. Or they receive a written dialogue and are asked to analyze violations of the principles that will be outlined below.

Gandhi, the man, his deeds, and his writings have made such a profound impact on millions of people that it is felt all their lives, even if it does not always show up in social conflict activism. People’s veneration is serious and honest, but few have had, or even try to get, training to face opponents or “antagonists” in a Gandhian way.

The way Gandhi at times described the views of people who opposed him and his influence has made a lasting impression. One deed that struck me as glorious belongs to the area of the practice of communication. Instead of giving a broad historical account I shall describe one series of communications.

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

Thornton Wilder published Heaven’s My Destination in 1935, seven years after winning the Pulitzer Prize for The Bridge of San Luis Rey. The main character, George Brush, is a Depression-era twenty-three year old. He is a socially awkward naïf; he seems a simpleton to most people he meets. A traveling salesman, evangelist, and pacifist, he is at odds with general American sentiment regarding such things as money and worldly success, and he gets in trouble for proclaiming religious statements in public, often writing them on hotel desk blotters.

Front dust wrapper current edition; Harper Collins; cover photograph copyright © Getty Images

The mishaps of this misfit, his miss-steps, mistakes and misunderstandings repeatedly cause him discomfort. He is a kind of American Candide, a Don Quixote, or a Kafkaesque bumbler who never quite sees why his extreme idealism puts off so many people. Yet Brush is quite successful at selling schoolbooks, and he has a great singing voice, so he appears attractive to some people some of the time. But as soon as he begins talking about his theories and beliefs he loses people’s sympathy.

Thornton Wilder once wrote that “Art is confession; art is the secret told.” What is the “secret” expressed in the story of Heaven’s My Destination? I would suggest it is that humanity is disappointingly cynical, and our faiths only roughly approximate higher principals; they are not perfect guides, which we can force others to accept as their own. The implications of this open secret for learning as we go through life, for finding a viable path, are profound. I think this book written nearly eight decades ago tells a fable still valuable in our time, which has its own extremists. By depicting the curious antics of an extremist, it shows us what it takes to make a “true believer” begin to take idealistic teachings with a grain of practical salt. It shows that it is not wise to be too vehement in inflicting our doctrines on others, and that literalism is dangerous, causing nice people to act like fanatics.

Read the rest of this article »

by Simon Moyle

Those who attempt to work for social change, especially in terms of peace work, are no strangers to despair. The task can seem so great, and our efforts so small, that victories seem impossible, the problems insurmountable. People’s attitudes take forever to change, if they change at all. Malevolent forces seem to have all the power, the weapons, the resources, the inertia, the media, and even the culture captive. Many refuse even to begin the work for this reason.

Gandhi also noted this fact in his book Hind Swaraj (or Indian Home Rule) in a section I think it is worth quoting at some length. In it he explains why he believes that the force of “love” (which he says “is the same as the force of the soul or truth”) is the greatest power in history:

“The fact that there are so many still alive in the world shows that it (satyagraha) is not based on the force of arms but on the force of truth or love. Therefore, the greatest and most unimpeachable evidence of the success of this force is to be found in the fact that, in spite of the wars in the world, it still lives on. Thousands, indeed tens of thousands, depend for their existence on a very active working of this force. Little quarrels of millions of families in their lives disappear before the exercise of this force. Hundreds of nations live in peace. History does not and cannot take note of this fact. History is really a record of every interruption of the even working of this force of love or of the soul…History, then, is a record of an interruption of the course of nature. Soul-force, being natural, is not noted in history.”

Read the rest of this article »

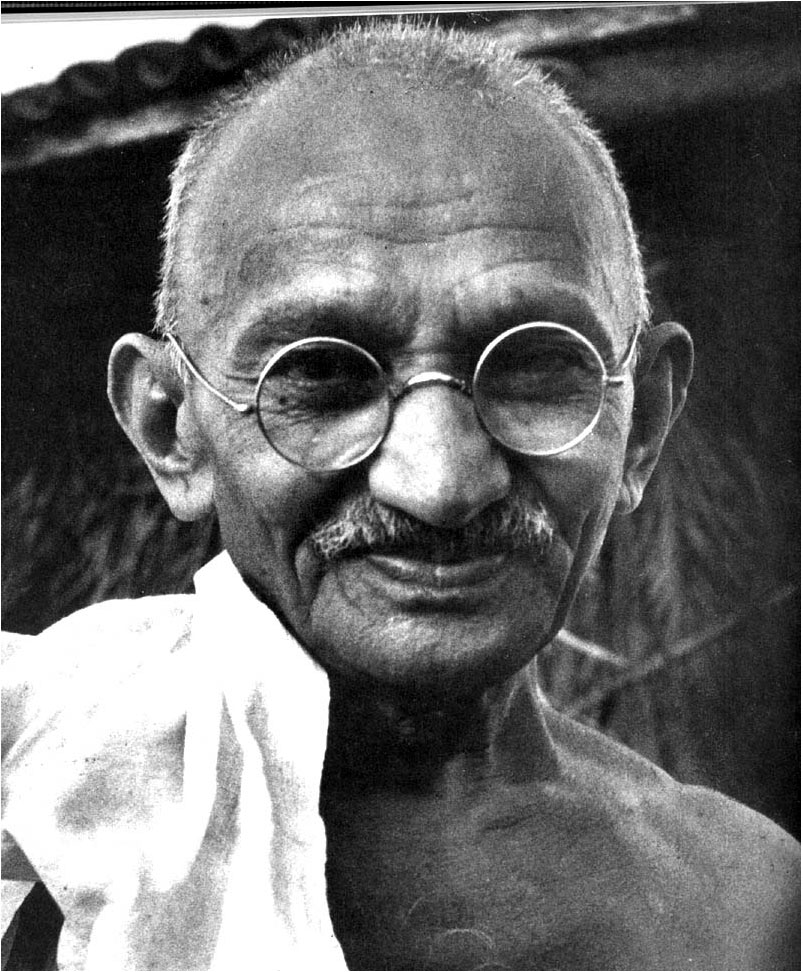

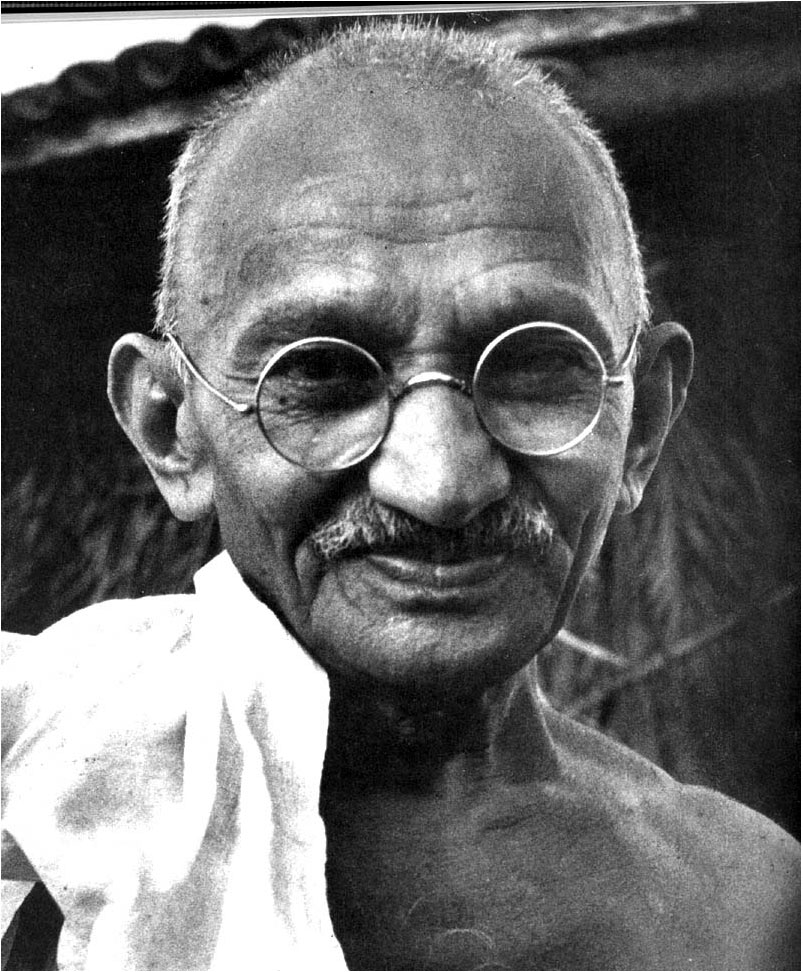

Gandhi c. 1945; photographer unknown;

a public domain image,

courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Changing the world begins with changing yourself; you have to become the change you want to see in the world.” M. Gandhi

The most Gandhi-like person I know is a very patient and gentle yogi who lives in New Delhi. When I wrote to him to say that I was preparing this article, he replied, “Making an honest and sincere attempt to practice exactly what one preaches is not easy—but Gandhiji did it to near perfection; at the cost of enormous physical as well as mental hardship, he examined his life in light of his convictions with brutal honesty, and underwent enormous inner suffering whenever he found himself wanting. That can give much greater torture than giving up physical comforts voluntarily, in which he also went to an extreme.”

Why was Gandhi so scrupulous? He himself said: “You have to become the change you want to see in the world.” Gandhi said that he thought Leo Tolstoy was the embodiment of truth in the age in which they lived: “Tolstoy’s greatest contribution to life lies, in my opinion, in his even attempting to reduce to practice his professions without counting the cost.” Gandhi said that reading Tolstoy’s writing “The Kingdom of God is Within You” changed his life, turning him from a votary of violence to an exponent of non-violence. Like Martin Luther King Jr., whom he inspired in turn, Gandhi always seemed ready to put comfort aside and to put his life on the line, without counting the cost. For example, when a leper came to his door in South Africa, Gandhi fed him, offered him shelter, dressed his wounds, and looked after him.

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

Gandhi: Merely a Man

We find two diametrically opposed views of Mohandas K. Gandhi’s moral stature. One states that, ethically speaking, he was nearly perfect. Albert Einstein said of him, for instance, that generations to come would scarcely believe that such a man actually walked this earth, and in a collection of essays that appeared under the title Gandhi Memorial Peace Number (Roy 1949), a large number of eminent persons accord Gandhi the highest of praise as a moral being.

We must also ask ourselves, however, what exactly is the nature of Gandhi’s contribution and what is the basis for the tremendous esteem and adulation in which he has been held. For with regard to his own moral achievement, we find a second opinion that is, perhaps, as near the truth as the first: the opinion that Gandhi was often mistaken and that it would be wrong to take him unreservedly as a moral example for everyone.

The best-known representative of this latter and more modest view happens to be Gandhi himself. “I claim no infallibility. I am conscious of having made Himalayan blunders . . .” (quoted in Pyarelal 1932: 133; also in Prabhu and Rao 1967: 9). There are other people also who firmly accept that he fell short of his own very high aims. The best collection of Gandhi’s teaching, The Mind of Mahatma Gandhi, compiled by Ramachandra K. Prabhu and U. R. Rao (1946, revised and enlarged in 1967), opens with two chapters in which Gandhi speaks of his own personal imperfection, his mistakes, their painful consequences, and his unrequited desire for support.

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

Truth: Absence of Theology: Pragmatic and Agnostic Leanings

Any adequate account of Gandhi’s ethics and strategy of group conflict must take account not only his most general and abstract metaphysical ideas, but also the religious content of his sermons. His basic ideas and attitudes influenced his concrete norms and hypotheses and his conflict praxis. His numerous public prayers were part of his political campaigns, his political campaigns part of his dealings with God.

Gandhi considered himself a Hindu. He gives a condensed characterization of his belief in Hinduism and his relations to other religions in his article “Hinduism”(Young India 6.10.19 21).

Yet, Gandhi found Truth in many religions and faiths, and this explains why his teaching on group conflicts has no definite theological premises. This passage elaborates: “You believe in some principle, clothe it with life, and say it is your God, and you believe in it. . . . I should think it is enough.” (Harijan 17.6.1939).

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

Introductory Remarks: Aim of the Systematization

Any normative, systematic ethics containing a perfectly general norm against violence will be called an ethics of nonviolence. The content will show variation according to the kind of concept of violence adopted. In order to do justice to the thinking of Gandhi, the term violence must be viewed broadly. It must cover not only open, physical violence but also the injury and psychic terror present when people are subjugated, repressed, coerced, and exploited. Further, it must clearly encompass all those sorts of exploitation that indirectly have personal repercussions that limit the self-realization of others.

The corresponding negative term nonviolence must be viewed very narrowly. It is not enough to abstain from physical violence, not enough to be-have peacefully.

In what follows, we offer a condensed systematic account of the positive ethics and strategy of group struggle, trying to crystallize and make explicit the essentials. We use the adjective positive, because the systematization does not include a treatment of evils, for instance, a classification into greater and less great evils. (Whereas violence is always an evil, it is sometimes a greater evil to run away from responsibility.)

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

The Contemporary Reaction against Nonviolence

The period spanning the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s witnessed an upsurge of physical violence and a proliferation of recommendations to use manifest violence, physical and verbal. It inundated colonial, racial, and educational controversies in Europe, America, India, and many other areas. Sometimes it has been systematically and consistently anti-Gandhian, being in part a direct reaction against the limited success of Gandhian and pseudo-Gandhian preaching and practice.

We shall not enter here into the controversies about the causes of this development, which we vaguely characterize as the “new violence.” A symptom, rather than a cause, is widespread dissatisfaction, indignation, and impatience when considering the slowness of the movement of liberation in the colonial, racial, and educational spheres. The imperatives “Do it quicker!” and “Freedom now!” testified to this demand for immediate, radical change. The slogan “Revolution!” has invaded all spheres of discussion. Revolution is generally conceived as a violent overthrowing, idealizing “power over” and coercion at the cost of “power to.” Changes should be forced on opponents; agreement and compromise should be shunned. The slogans are sometimes formed consciously so as to be in direct opposition to the preaching of nonviolence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Lloyd I. Rudolph

My title is figurative, not literal; Gandhi never set foot on American soil. His presence is the result of American responses to his person, ideas, and practice. For most Americans, they were exotic, often alien, fascinating for some, threatening or subversive to others. This chapter analyses America’s reception and understanding of Gandhi by pursuing two questions: Is he credible’? Is he intelligible?

For a person to be credible, it must be possible to believe that this seemingly quixotic person is someone like ‘us’: someone who makes sense in terms of America’s cultural paradigms and historical experience. From the beginning many thought that Gandhi was putting ‘us’ on, that he was fooling us while fooling around. Was he for real or was he a fraud?

Read the rest of this article »