by Arne Naess

When making optimistic forecasts about the outcome of the struggle for freedom in India, Gandhi used to say that success depended on increasing the constructive programs. But since these always fell short of what Gandhi required, his forecasts were not wrong, but simply rendered invulnerable to criticism. If the main effort of the nationalist movement was expended on opposing the British, according to Gandhi, nothing good would come of it. But his advice to concentrate upon constructive planning, rather than upon fighting the British, was not taken seriously by the politicians who were ostensibly his followers. Naturally, such advice had little appeal; it demanded discipline and self-sacrifice.

Perhaps Gandhi failed to repeat his great warning often enough. We should at least remind ourselves of this possibility when judging his sensational prediction in 1920 that India could free herself from Britain within a year. Naturally enough, this statement earned him both criticism and ridicule. (1) But Gandhi himself wrote: “Much laughter has been indulged in at my expense for having told the Congress audience at Calcutta that if there was sufficient response to my programme, of non-cooperation, swaraj [freedom] would be attained in one year.” (2) He had appealed to his countrymen to support his constructive efforts and called on them to form their own unofficial institutions and their own economy, in addition to their campaign to break away from British institutions and reliance on British imports. In other words, Gandhi could only envisage swaraj on the assumption that his positive demands were to be taken up and acted upon. But relatively few people did act upon them. “The conditions I had set for the fulfillment of the formula, ’swaraj in a year’, were forgotten.” (3)

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

Many of Gandhi’s actions were, on the face of it, demonstrations of sheer lunacy. For instance, in 1931 he went unguarded into the textile manufacturing areas of England, though told that he would certainly be killed if he did so. The terrible unemployment of that year had hit the textile workers especially hard. Indians were no longer buying textiles to the extent that they had done before. Moreover, the campaign for home industries, which Gandhi had organized in India, had had a powerful effect, and the British Press was not slow to blame Gandhi for the sufferings of the workers. In fact the newspapers, eager to find a scapegoat for the dreadful privation and suffering of their public, greatly exaggerated and distorted his role.

In spite of all warnings, Gandhi went to the workers, defenseless and trusting. And it was not just to show sympathy with the textile industry’s view of the crisis that he went. On seeing the textile workers’ actual living conditions, he pointed out to them how fantastically rich they were, compared with the poor of India, and he followed up this surprising statement by saying that the economic aims of the textile industry were unrealistic; they had not been formulated, he said, with any understanding of the European crisis as a whole. One would expect such words to have provoked bitter reaction, but Gandhi’s manner, marked by humor, trust, respect, and compassion, made it extremely difficult to oppose him. The workers gave him time to present his views, and they managed ultimately to divert their hatred from individual persons. They ceased to be his enemies and became his potential fellow-workers.

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

Gandhi’s attitude toward atheists and atheism has seemed to many people both paradoxical and inconsistent. What are we to say of his oft-repeated assertion that atheism could be part of the truth, so long as the atheist was as committed to his atheism as the theist to his theism? This from a man who not only regarded himself as an orthodox Hindu but also professed Godlessness to be nothing less than an abomination? It is of vital importance to be clear on this matter, since Gandhi’s attitude toward atheism can provide a key to our understanding of his position on theoretical issues in general.

We can gain a sense of this position partly in his transition from one to the other of the affirmations, “God is Truth” and “Truth is God,” partly in his attitude to other religions, and partly in the great weight he put on individual religiosity. His own statements indicate just how embracing his views of religion were, and these views enable us also to understand how it was that he could work together with atheists; for he conceived the aggressive morality of atheism as a genuinely religious attitude. Gandhi wrote in one of his more obscure sources, Yeravada Mandir, in a passage, which goes far to explain as well as demonstrate Gandhi’s tolerance for other religions: “As a tree has a single trunk, but many branches and leaves, so there is one true and perfect Religion, but it becomes many, as it passes through the human medium. The one Religion is beyond all speech. Imperfect men put it into such language as they command, and their words are interpreted by other men equally imperfect.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

How did Gandhi set about realizing his principle: “The essence of nonviolent technique is that it seeks to liquidate antagonisms but not the antagonists”?

It has long been the custom to speak of nonviolent as contrasted to military methods and techniques. But it should be noted that the distinguishing feature of a method or technique, as such, is that it is a mere instrument; the goal or aim toward which it works is something else. It is not necessary that the method or technique should have more than an instrumental value, only that it be employed unflinchingly toward the end in question. The kind of conduct Gandhi employed in group-conflict can, to some extent, be made into an organized system, but only to some extent. If the aspect of method is overstressed, we find ourselves interpreting Gandhi’s teaching as a kind of cookbook doctrine. One forgets his maxim: “Means and ends are convertible terms in my philosophy of life.”

In any campaign, according to Gandhi, moral principles must be observed. Such principles concern a man’s purity of intention, his respect for other individuals, and the absence in him of any tendency to look upon his fellow beings as means to an end. During campaigns, therefore, virtuous actions are to be performed, in part, because it is one’s duty to perform them, not merely because of advantages one hopes to reap from performing them.

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

“Satyagraha” is a word which connotes the typically Gandhian approach in political and social conflicts. Writing of the South African days Gandhi says that the expression ”passive resistance” was not an apt term for the action of the Indians in that country. Gandhi also rejected “pacifism.” He said that “We had to invent a new term clearly to denote the movement of the Indians in the Transvaal and to prevent its being confused with passive resistance generally so called.” (1) Satya means “truth” not in the purely theoretical sense of the way in which assertions correspond to reality, but rather in the sense in which we speak of someone as a true friend, in which we think of reality as a form of genuineness. Agraha means “grasp,” “firmness” or “fixity,” and Gandhi says, “Truth (satya) implies love, and firmness (agraha) engenders and therefore serves as a synonym for force. I thus began to call the Indian movement Satyagraha, that is to say, the Force which is born of Truth and Love or nonviolence, and gave up the use of the phrase ‘passive resistance,’ in connection with it.” (2) These and other general statements by Gandhi, of course, tell us almost nothing. They are too vague and it has become necessary, therefore, to distinguish various meanings of the new word satyagraha. According to one interpretation, satyagraha is the collective name for just those practical methods used by Gandhi in his campaigns. According to another, satyagraha designates the principles underlying Gandhi’s action; used in this sense, the word is practically a synonym for the concept of “power lying at the base of nonviolent means,” or simply for ahimsa. Thirdly, it is used as the common name for all the possible methods of action, whether exemplified by Gandhi or not, which are in agreement with the teachings of nonviolence; Gandhi’s methods, then, would be a subspecies of satyagraha—adapted to the special situations in which he worked. It is unfortunate that these three different meanings have been conflated, for considerable confusion inevitably arises in any discussion of satyagraha.

Read the rest of this article »

by Geoffrey Ostergaard

The early 20th century European anarchist-pacifist movement was early influenced by Gandhian nonviolence. Many anarcho-pacifists, such as Ostergaard and Bart de Ligt, found in satyagraha and Gandhi’s social programs the counterpart for the more violent European anarchist strains they were eager to reject. Ostergaard’s distinction between nonviolence as a moral principle and nonviolence as a political strategy seems more relevant now than when he wrote it in the 1980s; more central to debates within the Occupy Movement, and the nonviolent movement in general. This is the second in our series of historical articles that we began with Theodore Paullin’s “Introduction to Nonviolence”. The Editor’s Note at the end of the article presents biographical information about Ostergaard, sources, and credits.

Discussions of nonviolence tend, not unnaturally, to focus on the issue of the supposed merits, efficacy and justification of nonviolence when contrasted with violence. Here, however, I propose to pursue a different track. My object is to explicate the Gandhian concept of nonviolence and this, I think, can best be done, not by contrasting nonviolence with violence but by distinguishing two different kinds of nonviolence. My thesis, in short, is that, Janus-like, nonviolence presents to the world two faces which are often confused with each other but which need to be distinguished if we are to appraise correctly Gandhi’s contribution to the subject.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mohandas K. Gandhi

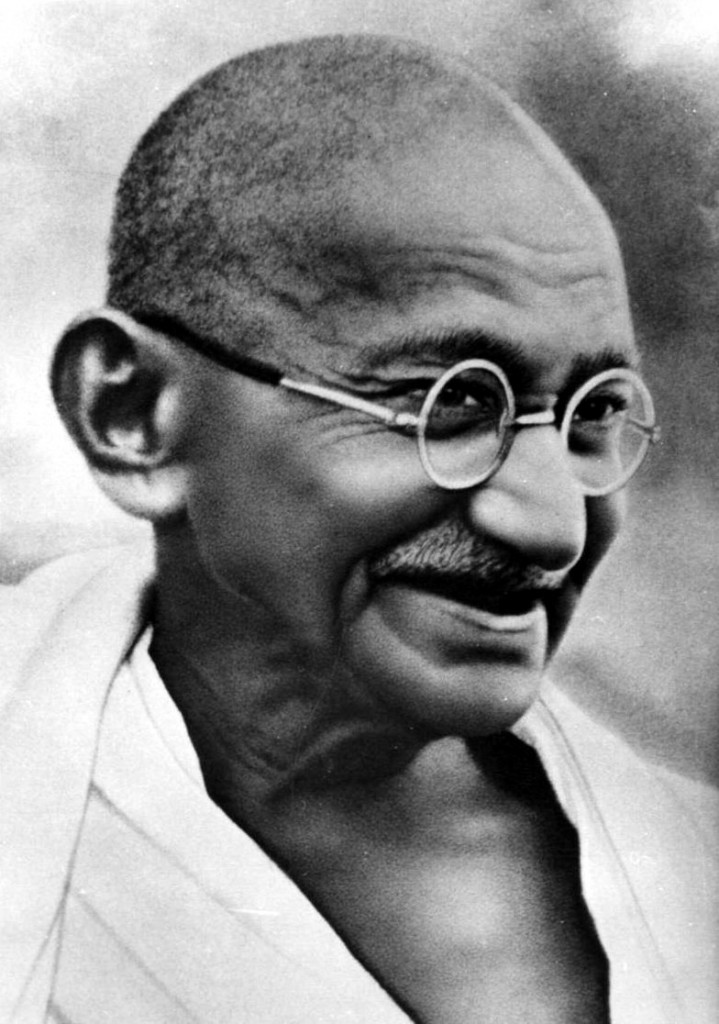

Gandhi, c.1948; public domain image, courtesy commons.wikimedia.org; photographer unknown.

After Indian independence, Gandhi advocated the dissolution of the main political party, the Indian National Congress, which he had previously led. The struggle had shifted, he said, from securing independence to seeing to the needs of the people. Party politics could not serve this purpose and so he conceived of more localized structures to be called Lok Sevak Sangh, or the Servants of the People. Just weeks before his assassination, Gandhi drafted a constitution for Lok Sevak Sangh, which Geoffrey Ostergaard refers to in his article also posted today. Lok Sevak Sangh has not been given enough attention, but bears comparison with anarcho-syndicalism, the Muslim Brotherhood’s social program, or the current emphasis of the Occupy Movement on social programs. The draft constitution was published on 15 January 1948. Two weeks later, on 30 January, Gandhi was assassinated.

The Draft Constitution:

Though split into two, India having attained political independence through means devised by the Indian National Congress, the Congress in its present shape and form, i.e., as a propaganda vehicle and Parliamentary machine, has outlived its use. India has still to attain social, moral and economic independence in terms of its villages as distinguished from its cities and towns.

The struggle for the ascendancy of civil over military power is bound to take place in India’s progress towards its democratic goal. It must be kept out of unhealthy competition with political parties and communal bodies. For these and other similar reasons, the AICC resolves to disband the existing Congress organization and flower into Lok Sevak Sangh, the Servants of the People, under the following rules with power to alter them as occasion may demand.

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

It was Gandhi’s claim that the greater the efficiency he acquired in the use of nonviolence, the greater the impression nonviolence made on his opponents. This claim he held to be a legacy of his experiences in South Africa. Was he right in this? Did his claim follow, according to inductive principles, as a valid conclusion from what he saw?

The railway-strike episode and others of a similar kind did, in fact, provide Gandhi with an empirical basis for the hypothesis that the more he applied, even to fanatical extremes, the principle of nonviolence, the greater was its effect, and that every increase, no matter how slight, in the purity of the application of the principle meant an increase in the chances of success. Thus we can see what was meant by Gandhi’s seemingly extreme claim that if one man were able to achieve an entirely perfect, nonviolent method, all the opposition in the world would vanish. Yet we must be careful to note that Gandhi explicitly stated that we are all more or less imperfect, not least himself, and that therefore we can talk only in terms of degrees of success and not perfection.

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

Some of Gandhi’s fellow-workers, just as some of Nehru’s in a later day, were Socialists and Marxists. Though critical of their views, Gandhi was far from negatively disposed toward their aims. He believed, however, that it could not be in the employer’s interests to behave badly toward the workers, and that the employer could be persuaded to make radical reforms. On the basis of psychological and social interests common to both sides, he believed it impossible, in the long run, for one group to profit at the expense of the other. Exploitation and oppression amounted to violence, in Gandhi’s terms, and could only drive participants apart.

Today we might well admit that the acceptance of Gandhi’s view could have spared us Lenin’s uncritical acceptance of means and also the kind of laissez-faire liberalism we find in Western Europe, a liberalism which rejects all measures of economic control to remedy the undeserved suffering of the poor. We have seen in our time how both of the political philosophies from which these economic views are derived have led to violence and oppression.

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

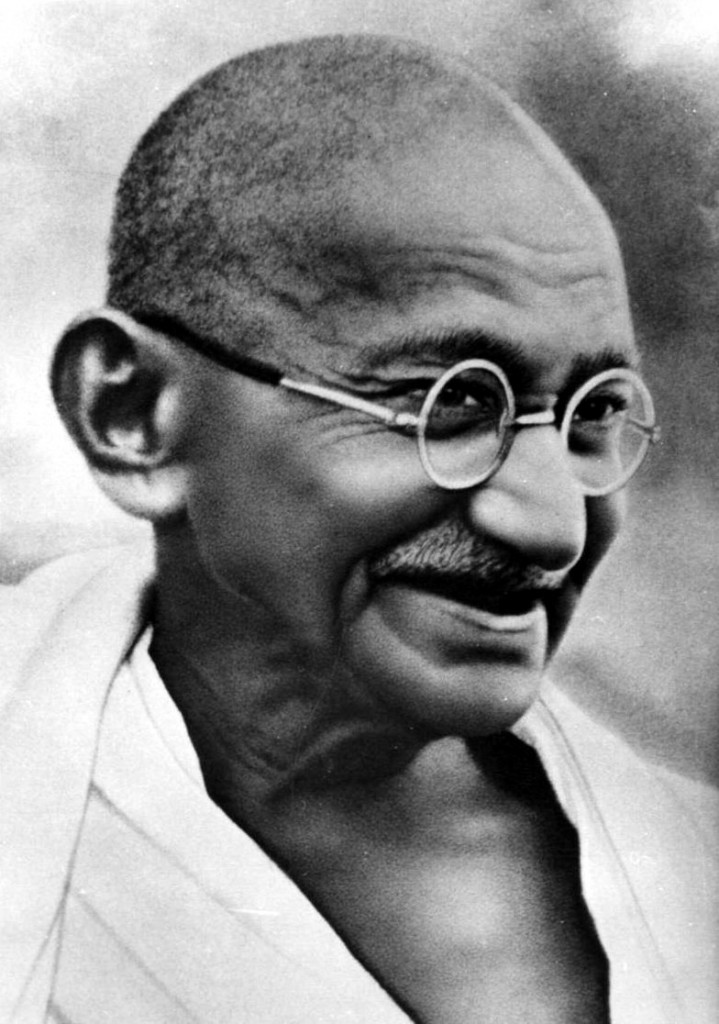

Gandhi on the Salt March, 1930; public domain photo; photographer unknown

The image of Gandhi in action, walking with a staff in his hand, is well known. We see it in newsreels, statues, films and photos. Thomas Merton described Gandhi as a human question mark. Perhaps we should amend that to “a walking human question mark” moving across the landscape. He was a man on the move, inquiring why injustices exist and how to remedy them.

When Gandhi returned to India after being away for years studying in England and practicing law in South Africa, he tirelessly traveled all over the subcontinent. He went to places where he was invited to resolve conflicts, and was constantly taking the pulse of the people of India, assessing their needs and views, diagnosing the nation’s ills, and, when possible, trying to address them with his legal expertise. During much of this period he traveled by trains in third class cars.

Read the rest of this article »