by Nathan Schneider

Gene Sharp collage; artist unknown; courtesy of Socialistplatform

There is something of a genre of critique, one sometimes lobbed at Waging Nonviolence, which considers the discourse of nonviolence to be wholly subservient to the U.S. foreign policy interests, and/or the CIA specifically. It’s a line of attack that has generally baffled us, since anything worthy of the name “nonviolence” would certainly run counter to the doings of the largest and most pervasive military machine in the history of the world. Occasionally there seems to be some truth in these critiques, but it’s hard to know where that begins and the conspiracy-theory nonsense ends.

Now I think I know where to begin to draw the line. The reason is a new paper published in the journal Societies Without Borders in September by Sean Chabot and Majid Sharifi. It’s called “The Violence of Nonviolence: Problematizing Nonviolent Resistance in Iran and Egypt.”

Read the rest of this article »

by John Scales Avery

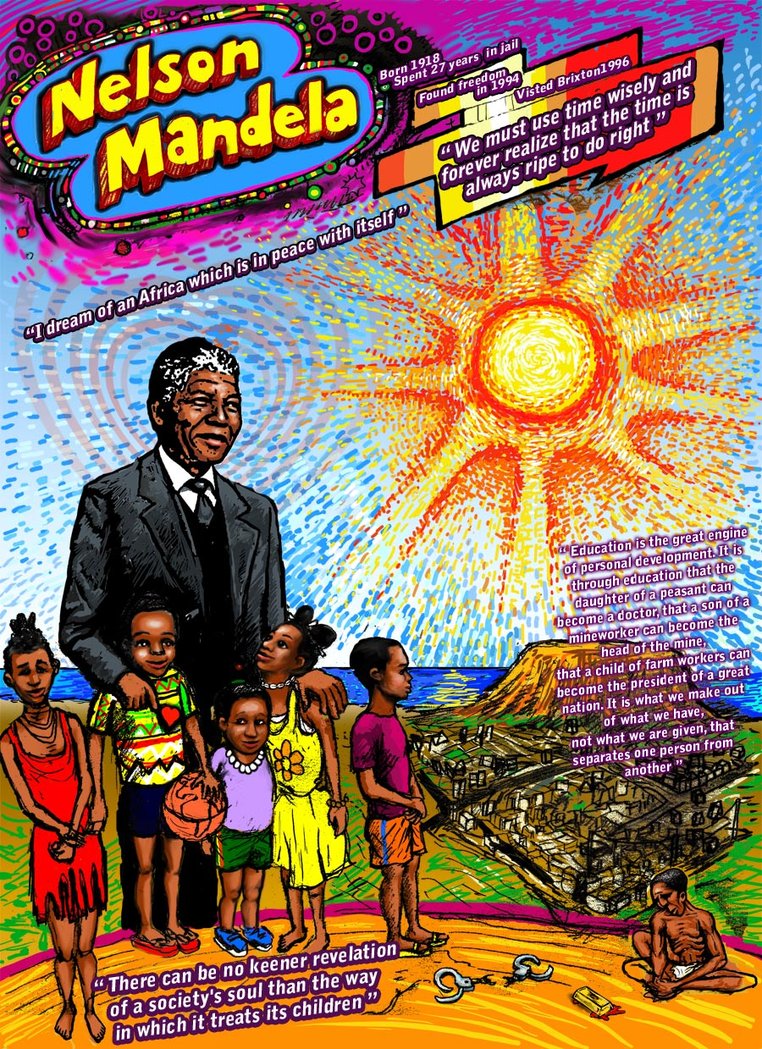

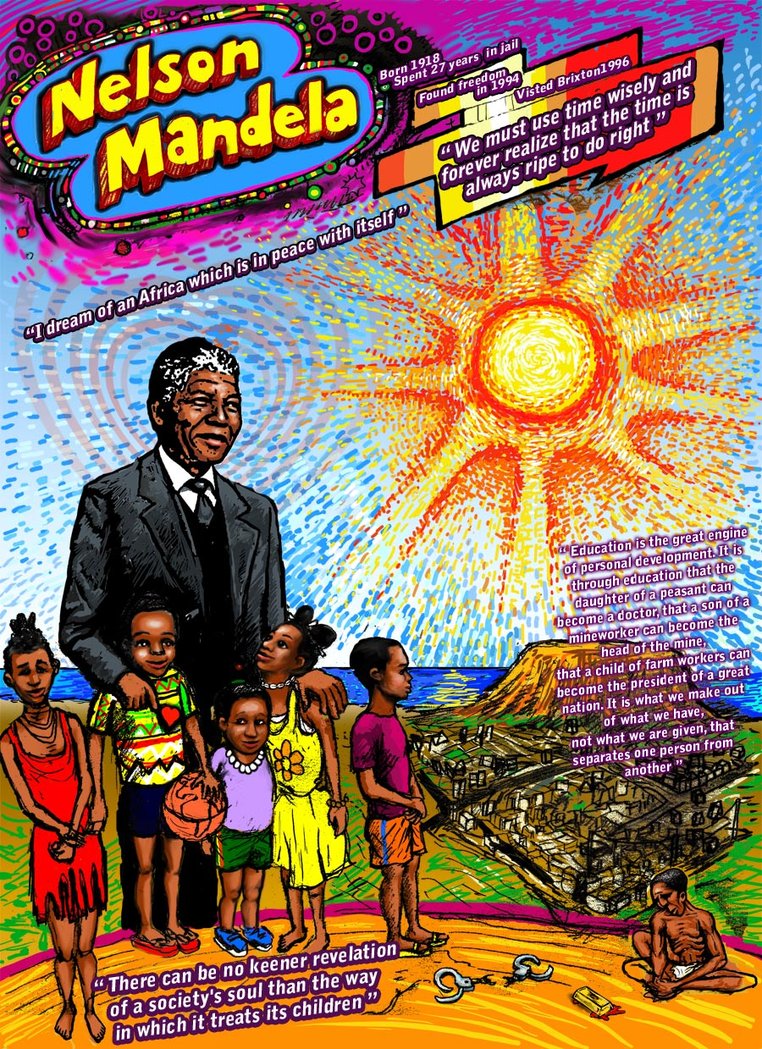

Design for a mural in Brixton, South London; design by mORGANICo-cOM

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (1918-2013) and Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) were two of history’s greatest leaders in the struggle against governmental oppression. They are also remembered as great ethical teachers. Their lives had many similarities; but there were also differences.

Similarities

Both Mandela and Gandhi were born into politically influential families. Gandhi’s father and grandfather were dewans (prime ministers) in Porbandar, a district of the Indian state of Gujarat. Mandela’s great-grandfather was the ruler of the Thembu peoples in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. When Mandela’s father died, his mother brought the young boy to the palace of the Thembu people’s regent, Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo, who became the boy’s guardian. He treated Mandela as a son and gave him an outstanding education.

Both Mandela and Gandhi studied law. Both were astute political tacticians, and both struggled against governmental injustice in South Africa. Both were completely fearless. Both had iron wills and amazing stubbornness. Both spent long periods in prison as a consequence of their opposition to injustice and both are remembered for their strong belief in truth and fairness, and for their efforts to achieve unity and harmony among conflicting factions. Both treated their political opponents with kindness and politeness.

Read the rest of this article »

by Stephanie Van Hook

Gandhi in prayer c. January 1948, shortly before his assassination; photographer unknown; courtesy of commons.wikimedia.org

I am praying for the light that will dispel the darkness.

Let all those with a living faith in nonviolence join me in this prayer.

M.K. Gandhi

Gandhi was once given a seemingly impossible scenario: what would he do if a plane were flying over his ashram to bomb him? He rose to the challenge with an equally challenging answer: he would pray for the pilot. Some may take Gandhi’s response as preposterous. I argue, however, that his call to prayer was consistent with his vision of nonviolent strategy, for at least three reasons.

Reason 1: It meets the escalation of physical force with soul force.

Nonviolence requires strategic thinking; in other words, it requires a knowing of how to switch from one mode of operation to another in response to how the conflict is progressing. When a conflict escalates, a strategic response should also be prepared to escalate, not just with new tactics, but also through the depth of the nonviolence itself. Dr. King echoes this idea in his Dream speech, that the freedom struggle would meet “physical force with soul force.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Ashis Nandy

There are four Gandhis who have survived Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s death. Fifty years after Gandhi’s assassination (1861-1948), it may be useful to establish their identities, as the British police might have done in the high noon of colonialism. All the four Gandhis are troublesome, but they trouble different people for different reasons and in different ways. They are also useable in contemporary public life in four distinct ways. I say this not in sorrow, but in admiration. For the ability to disturb people — or, for that matter, be useable — one hundred and thirty years after one’s birth and fifty years after one’s death is no mean achievement. Frankly, I do not care who the real Gandhi was or is. Let academics debate that momentous issue. Contemporary politics is not about ‘truths’ of history; it is about remembered pasts and the problems of fashioning a future based on collective memories. For better or for worse, Gandhi seems to have entered that memory.

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

When I taught university courses in which students read and discussed Gandhi’s Autobiography, I always found it rewarding to consider the early formative influences in his life, which Gandhi discussed in the opening chapters. These influential experiences are interesting to consider, because as Wordsworth wrote, “The child is father to the man.”

Mohandas Gandhi’s father had “rich experience of practical affairs” though he was uneducated in fields like history and geography. (Mohandas K. Gandhi, Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth, New York: Dover Publications, 1983, p. 2) His mother made an impression of saintliness, with practices of daily prayer and fasting. One practice was vowing not to eat during the day until seeing the sun. Gandhi and his brother would run out on cloudy days and look at the sky when it seemed the sun was coming out, then run back in and tell her they saw the sun. And she would go out and look, and not seeing the sun, would continue fasting, cheerfully saying, “God did not want me to eat today.” She was a daily lesson in loyalty to a vow, self-control, and self-deprivation. (pp. 2-3)

Read the rest of this article »

by Mary Elizabeth King

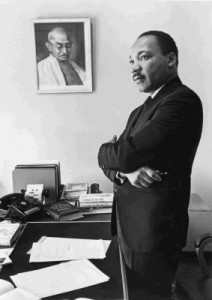

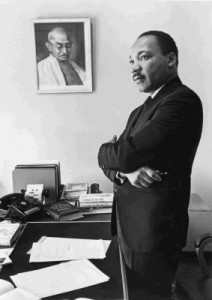

How does one learn nonviolent resistance? The same way that Martin Luther King Jr. did—by study, reading and interrogating seasoned tutors. King would eventually become the person most responsible for advancing and popularizing Gandhi’s ideas in the United States, by persuading black Americans to adapt the strategies used against British imperialism in India to their own struggles. Yet he was not the first to bring this knowledge from the subcontinent.

Martin Luther King, Jr. beside a picture of Gandhi; photograph © Bob Fitch

By the 1930s and 1940s, via ocean voyages and propeller airplanes, a constant flow of prominent black leaders was traveling to India. College presidents, professors, pastors and journalists journeyed to India to meet Gandhi and study how to forge mass struggle with nonviolent means. Returning to the United States, they wrote articles, preached, lectured and passed key documents from hand to hand for study by other black leaders. Historian Sudarshan Kapur has shown that the ideas of Gandhi were moving vigorously from India to the United States at that time, and the African American news media reported on the Indian independence struggle. Leaders in the black community talked about a “black Gandhi” for the United States. One woman called it “raising up a prophet,” which Kapur used as the title of his book.

While a student at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, King was intrigued by reading Thoreau and Gandhi, yet had not actually studied Gandhi in depth. A friend, J. Pius Barbour, remembered the young seminarian arguing on behalf of Gandhian methods with a reckoning based on arithmetic—that any minority would be outnumbered if it turned to a policy of violence—rather than on principle.

Read the rest of this article »

by Christian Bartolf

Four times Gandhi offered his services to the army: in 1899-1900 during the Boer War, in 1906 on the occasion of the so-called Zulu Rebellion, in 1914 during his stay in London at the outset of World War I; and lastly in India in 1918 near the conclusion of that war. After World War I Gandhi on a number of occasions was asked how he could reconcile his participation in war with his principle of nonviolence (ahimsa). Bart de Ligt was not the only person to correspond with Gandhi on this issue, but he was the most forthright and compelling. Leo Tolstoy’s friend and secretary, Vladimir Tchertkov, had also questioned Gandhi about it. In fact, it was a common reverence for Tolstoy’s doctrine of non-resistance or non-violent resistance that was the foundation for the critical dialogue between Bart de Ligt and Gandhi between 1928 and 1930. As an introduction to this correspondence, we shall first summarize Gandhi’s participation in various wars, and the exchanges of letters and conversations, which Gandhi had on this matter, including his dialogue with Bart de Ligt.(1)

Read the rest of this article »

In the years immediately following World War I, Western pacifists were seeing with alarming clarity the possibility of another war, and speaking out with increasing urgency against militarism. Having suffered through the trauma of appalling destruction, pacifist writing in the 1920s and 1930s has the aura of a survival myth. The advent of Gandhian satyagraha presented pacifists with a possible strategy for averting tragedy, as an antidote to war, and moved Bart de Ligt to write publicly and openly to Gandhi, to enlist him in the pacifist cause. Gandhi’s nonviolence was never a fixed principle; was ever evolving. The Salt March of March 1930, which some see as pivotal to the development of Gandhian nonviolent resistance, had not yet taken place when these letters were published. On the one hand, there are pacifists determined to staunch the advent of another daimonic war, and on the other hand there is Gandhi in a death struggle with the British for Indian independence, his nonviolence, by his own admission, imperfect. De Ligt’s call for Gandhi to reject war, to commit satyagraha to the ending of war was a prophetic call. [JG]

Letter One: Bart de Ligt to Gandhi; May, 1928.

Most venerated Gandhi:

Without doubt, there is no man who attracts the attention of the modern world as you do. And you are certainly worthy of this admiration because you have been able in a wise, heroic way to awaken everywhere confidence in that moral force which slumbers in each individual. To oppose the severe oppression of so-called Christian civilization, and the violence of proud and pretentious Westerners, you have awakened in the East immense spiritual forces, making it seem that Christ reigns over your “pagan” world rather than in our official Christian churches. You have not only proclaimed the gospel of non-resistance — or spiritual warfare — but you have yourself practiced it and have paid with your own person.

Read the rest of this article »

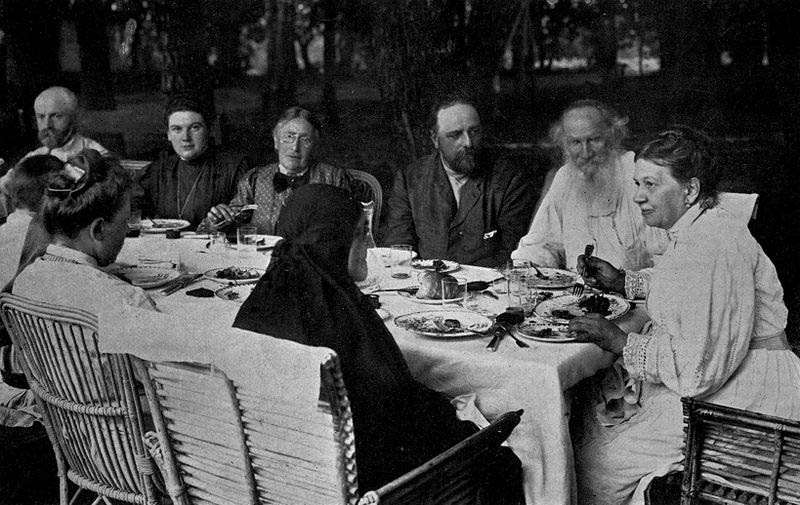

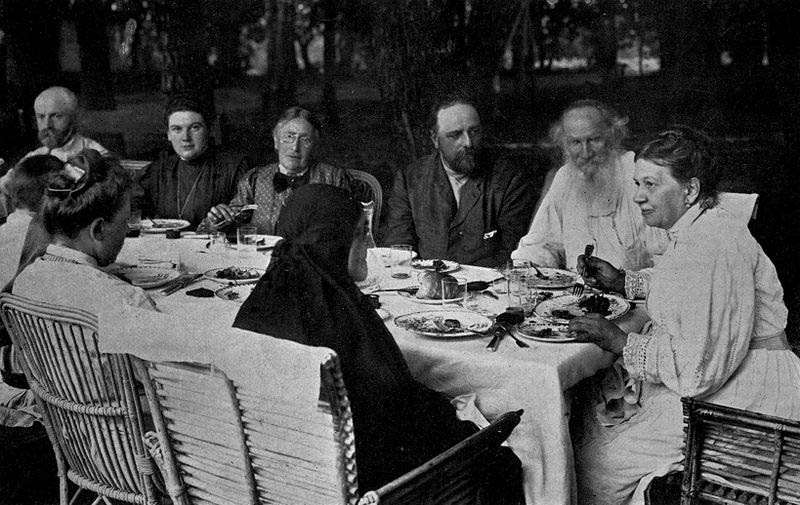

Tolstoy family gathering, 1905; Tchertkov to Tolstoy’s right; photographer unknown.

My article, “My Attitude Towards War”, published in Young India, 13th September 1928, has given rise to much correspondence with me and in the European press that is interested in war against war. In the personal correspondence there is a letter from Tolstoy’s friend and follower, V. Tchertkov, which, coming as it does from one who commands great respect among lovers of peace, the reader will like me to share with him. Here is the letter:

Personal Letter from Vladimir Tchertkov

Your Russian friends send you their warmest greetings and best wishes for the further success of your devoted service for God and men. With the liveliest interest do we follow your life, the work of your mind, and your activity, and we rejoice at each of your successes. We realize that all that you attain in your own country is at the same time also our attainment, for, although under different circumstances, we are serving the one and the same cause. We feel a great gratitude to you for all that you have given and are giving us by your person, the example of your life, and your fruitful social work. We feel the deepest and most joyous spiritual union with you.

Read the rest of this article »

by Bart de Ligt

From Germany, Austria and other countries, I have been urged for information about my correspondence with Gandhi, which so far has only been published in French, English and Dutch and for various reasons could not be published in German. I am therefore most grateful to the editorial staff of Neue Generation (New Generation) for the opportunity to acquaint you with a few matters.

It was only in 1928 that I could really go more profoundly into Gandhi’s life. I had read, of course, with great interest a number of his articles. As well as that, I had taken note of various articles written about him. The most important insights I owe to the short book by Romain Rolland (Mahatma Gandhi, 1922) and a few articles published in magazines.

From these I came to understand Gandhi as the legitimate follower of Tolstoy. Whereas Tolstoy would have been the “John the Baptist” of revolutionary nonviolence, Gandhi would have been the Christ, so to speak, of this movement; Tolstoy the Great Precursor and Prophet, Gandhi the Performer fulfilling the Prophecy.

Read the rest of this article »