by Anne Pearson

Are Gandhian ideals dead in India? Some people have thought so as India’s political leadership since India’s achievement of independence in 1947 has largely ignored Mahatma Gandhi’s prescriptions for economic, political and social development. Even so, apart from such notable figures as Vinoba Bhave and Jayaprakash Narayan, both of whom led mass movements for social change respectively in the 1960s and ’70s, there have been some stalwart Gandhians who have continued to attempt to put the Mahatma’s ideals into practice. One of these figures is 91-year-old Acharya Ramamurti, a man who in his twilight years has recently inaugurated a new social movement aimed at integrating village and district level democracy with nonviolence and the rights of women. His nonpartisan movement has been meeting with spectacular success. Tens of thousands of women have now been trained in a women’s peace corps and their collective efforts are beginning to change the social and political climate in parts of northern India.

Gandhi’s Call to Women

Mahila Shanti Sena conference, Bihar 2001; courtesy of McMaster University

Gandhi had long believed that women had special capacities for sacrifice and for leadership in peace building. He thought that the world had been too long dominated by “masculine” aggressive qualities and that it was time that the “feminine” qualities came to the fore. He wrote: “Nonviolence is woman’s inborn virtue. For ages man has been trained in violence. To become nonviolent they will have to generate womanly qualities. Since I have adopted nonviolence, I am myself becoming womanly day by day. Women are accustomed to making sacrifices for the family. They will now have to learn to make an offering for the country. I am inviting all women… to get enlisted in my nonviolent army.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Mark Shepard

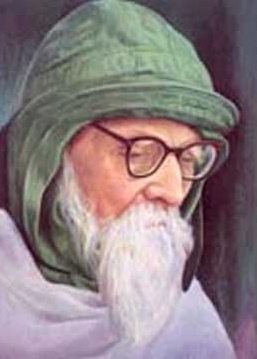

Vinoba Bhave; photographer unknown; courtesy of bharatmatamandir.in

Once India gained its independence, that nation’s leaders did not take long to abandon Mahatma Gandhi’s principles. Nonviolence gave way to the use of India’s armed forces. Perhaps even worse, the new leaders discarded Gandhi’s vision of a decentralized society, a society based on autonomous, self-reliant villages. These leaders spurred a rush toward a strong central government and a Western-style industrial economy. But not all abandoned Gandhi’s vision. Many of his “constructive workers”, development experts and community organizers working in a host of agencies set up by Gandhi himself, resolved to continue his mission of transforming Indian society. And leading them was a disciple of Gandhi previously little known to the Indian public, yet eventually regarded as Gandhi’s “spiritual successor”, Vinoba Bhave, a saintly, reserved, austere man most called simply Vinoba. How did he assume this status?

In 1916, at the age of 20, Vinoba was in the holy city of Benares trying to come to a decision about his life. Should he go to the Himalayas and become a religious hermit? Or should he go to West Bengal and join the guerillas fighting the British? Then Vinoba came across a newspaper account of a speech by Gandhi. He was thrilled, and soon after joined Gandhi in his ashram. Gandhi’s ashrams were not only religious communities, but also centers of political and social action. As Vinoba later said, he found in Gandhi the peace of the Himalayas united with the revolutionary fervor of Bengal.

Read the rest of this article »

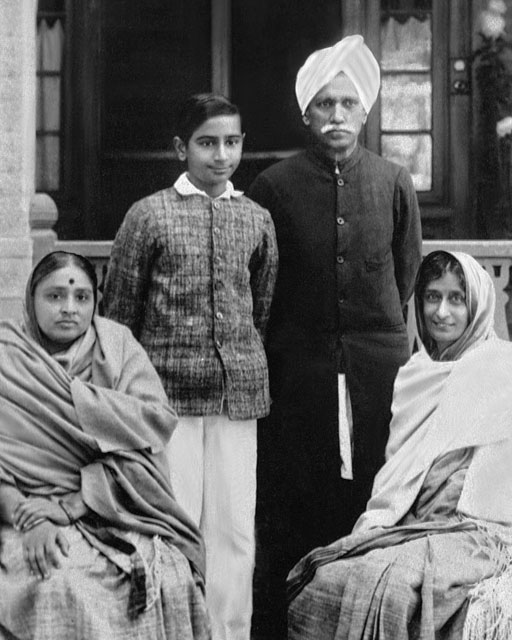

by Narayan Desai

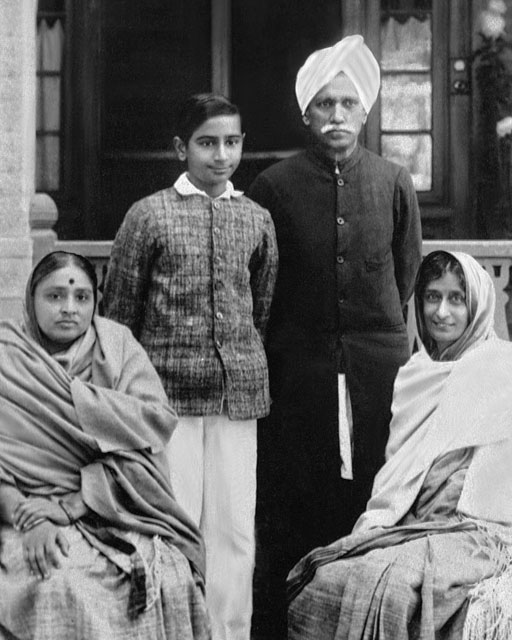

Editor’s Preface: Narayan Desai (b. 1924) is the son of Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s chief secretary until 1942. He is the founder of the nonviolence training center, the Institute for Total Revolution, and the author of a four volume biography of Gandhi among other works. He has been awarded both the Jamnalal Bajaj Award and the UNESCO Madanjeet Singh Prize for his work in nonviolence and pacifism. JG

Young Narayan Desai with parents; photo courtesy Narayan Desai

The Satyagraha Ashram of Mahatma Gandhi stood on the bank of the broad Sabarmati River, across from the city of Ahmedabad. “This is a good spot for my ashram,” Bapu used to say. All of us in the ashram called him Bapu, or Father. He added, “On one side is the cremation ground. On the other is the prison. The people in my ashram should have no fear of death, nor should they be strangers to imprisonment.” Indeed, my earliest memories of Bapu are intertwined with those of Sabarmati Prison. Bapu would go for a walk each morning and evening. He would put his hands on the shoulders of those to either side. These companions would be his “walking sticks.” We children were always given first choice for this job. Whether his human walking sticks were really any help to him, perhaps only Bapu could say. But as for us, being chosen always made us swell with pride. In fact, in our eagerness to be chosen Bapu’s “sticks”, we would sometimes clash.

Read the rest of this article »

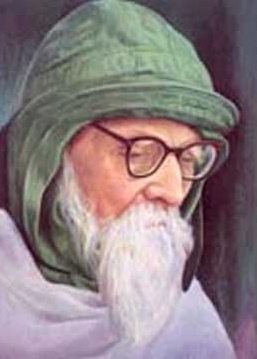

by Bharat Mansata

Bhaskar Save on 92nd birthday; photograph by the author

Bhaskar Save, acclaimed “the Gandhi of Natural Farming”, turned 92 on 27 January 2014, having inspired and mentored three generations of organic farmers. Masanobu Fukuoka, the legendary Japanese natural farmer, visited Save’s farm in 1996, and described it as “the best in the world”, ahead of his own farm. In 2010, the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) honoured Save with the “One World Award for Lifetime Achievement”.

Indeed, Save’s farm is a veritable food forest; a net supplier of water, energy and fertility to the local eco-system, instead of a net consumer. His way of farming and his teachings are rooted in a deep understanding of the symbiotic relationships in nature, which he is ever happy to explain in simple, down-to-earth idioms to anyone interested. Save’s 14 acre orchard-farm Kalpavruksha is located on the Coastal Highway near village Dehri, District Valsad, in southernmost coastal Gujarat, a few km north of the Maharashtra-Gujarat border. The nearest railway station is Umergam on the Mumbai-Ahmedabad route.

Read the rest of this article »

by Robert Ellsberg

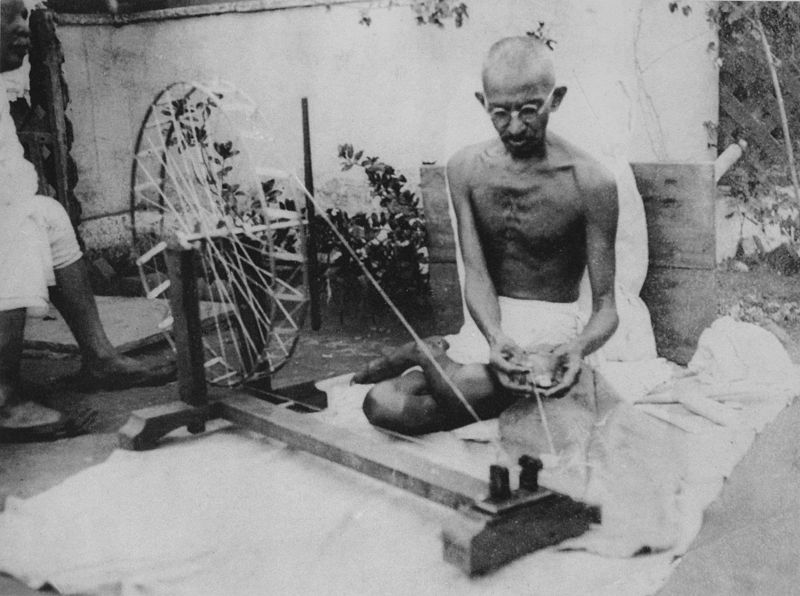

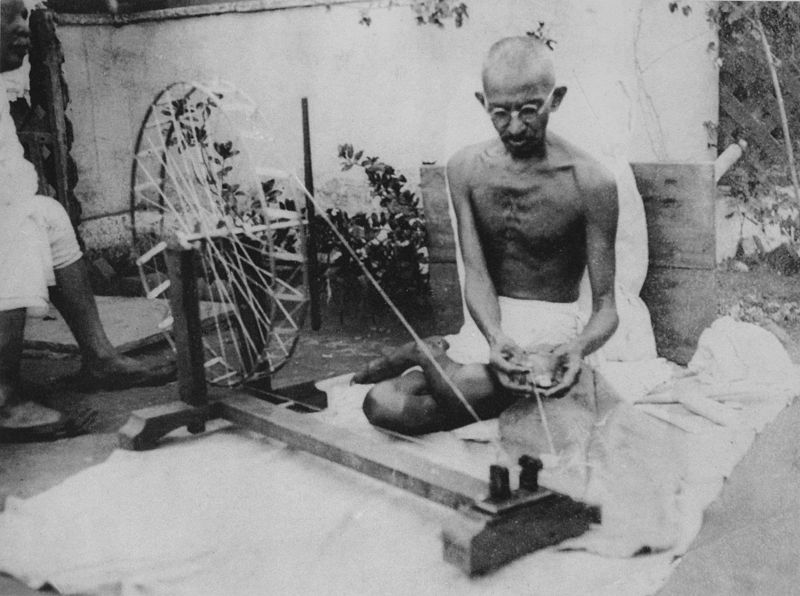

Gandhi spinning, c. 1945; photographer unknown; courtesy of wikipedia.org

“The outward freedom that we shall attain will only be in exact proportion to the inward freedom to which we have grown at a given moment. And if this is the correct view of freedom our chief energy must be concentrated upon achieving reform from within.” M. K. Gandhi

Thomas Merton observed that Gandhi’s spirit of nonviolence “sprang from an inner realization of spiritual unity in himself. The whole Gandhian concept of nonviolent action and satyagraha is incomprehensible if it is thought to be a means of achieving unity rather than as the fruit of inner unity already achieved.” Satyagraha in its sense of truth-force, or soul-force as Martin Luther King called it, could not be a means for overcoming division, unless it represented in itself the active experience of the unity of life; it could not secure a peace from without that was anything but the gift of its own being, a love rooted beneath the surface of things. For the satyagrahi each battle must first be fought in the soul—the battle against selfishness, attachment, passion. One could hardly begin the outer struggle—to wean the opponent from his or her selfishness, attachment, and passion, until the inner battle had been fought, and Truth had been victorious. The task was merely to re-enact that struggle on a larger stage. Truth never engaged in a struggle that had not already been won.

Read the rest of this article »

by Robert Ellsberg

Indira Gandhi, c. 1965; photographer unknown; courtesy of bollyworldbits.blogspot.nl

The Indian consulate in New York City occupies a stately building off of Fifth Avenue. I was arrested for distributing leaflets marking the first anniversary of Indira Gandhi’s State of Emergency. I was charged with disorderly conduct and obstruction of government administration. “Which government might that be?” I asked hopefully. “Whose jail are you in, buddy?” replied my arresting officer.

At that time, in India, tens of thousands of men and women were in jails and detention camps, among them the most active segments of the nonviolent Gandhian movement, for having committed crimes not much different than my own.

And now, more than two years later, the dark days in India, which began on June 26, 1975, have passed. In the spring of 1976, Mrs. Gandhi gave six-weeks notice that free elections would be held, scheduled for mid-March. The announcement itself came as no surprise; Indira’s power was confidently entrenched, most of the provisions of emergency rule (which was maintained throughout the election) were long since codified in law, or established in fearful precedent. It was obvious that elections under these conditions would accomplish no more than to legitimize and cement the existing constitutional dictatorship.

Read the rest of this article »

by Robert Ellsberg

Farm boycott swaraj poster; artist unknown; courtesy of dehligreens.com

“Sometimes a man lives in his dreams. I live in mine, and picture the world as full of good human beings—not ‘goody-goody’ human beings. In the socialist’s language there will be a new structure of society, a new order of things. I am also aspiring after a new order of things that will astonish the world. If you try to dream these daydreams you will also feel exalted as I do.” M. K. Gandhi

On the day of India’s independence, the consummation of a lifetime of struggle, Gandhi did not participate with other Congress leaders in the celebration. That day for him was an occasion of deep sorrow, which he observed by fasting. India’s future lay in the hands of those who were determined to pursue the path of industrial and military strength, centralization of the means of production and political power, men who believed that India could be remade from the top down.

As nonviolent revolution could not be the equivalent of violent revolution without the violence, but something qualitatively different in assumptions and goals, true swaraj (self-rule) could not be the parasitic apparatus of bureaucratic administration minus the British. Gandhi’s conception of swaraj was quite different: not the goal of an Indian nationalist government, but a process that would replace the state by the self-rule of each individual. As the best function of school should be to enable the student to educate himself, the role of government, as Gandhi saw it, was to make itself more and more unnecessary, by enabling people to do without it; not simply by eliminating its functions, but by encouraging self-reliance, personal responsibility and devotion to social welfare, while dispersing the means of administration among radically decentralized institutions through which the masses might learn the art of self-management. A true Independence Day could not be represented by the arbitrary date of British submission, but that time when each individual was self-governing and self-sufficient for his/her basic needs. Swaraj was the rule of nonviolence, order arising from freedom, not to pursue selfish passions and desires, but to submit voluntarily to the law of one’s being. That freedom was not a privilege or right guaranteed by constitution but a perpetual call to the soul. Swaraj was thus a moral principle, which embodied certain political principles and economic conditions: decentralism, village autonomy, self-sufficiency, voluntary poverty, and bread labor; it was a philosophy of work.

Read the rest of this article »

by Eileen Egan

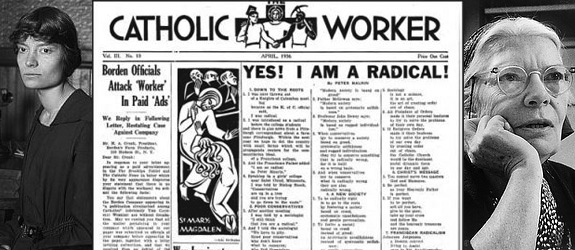

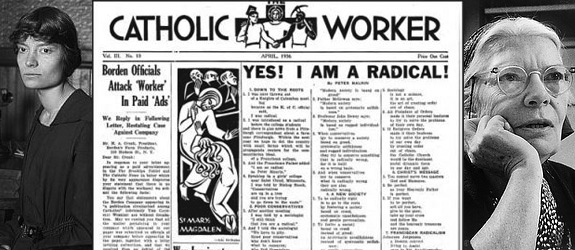

Photo collage with CW masthead; artist unknown; courtesy of the CW

Nonviolence has a negative, passive ring to it that its adherents have been attempting to erase by prefixing to it the adjective “militant.” Regrettably, it is the only current term in general usage in English. It corresponds to the Gandhian ahimsa, or non-injury, and carries the necessary message of unwillingness to injure or kill other creatures. For Western adherents of ahimsa or nonviolence who are not vegetarians, the unwillingness applies only to humans. The nonviolent person is not supine before an insane attack. The defense of a third party often involves the interposing of the body of the nonviolent person, with no intent of inflicting harm. Gandhi coined the term satyagraha, or truth-force, to describe a nonviolent campaign for human rights and freedom. As “God is Truth and Truth is God” in Gandhi’s thinking, the inference was that only godly or moral force would be employed by satyagrahi, participants in the nonviolent movement. Martin Luther King’s term, “soul-force” is a satisfactory one for most adherents of nonviolence.

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

Ahimsa logo; artist unknown; courtesy of thisisourstory.net

Examples of Nonviolence in Action

Ahimsa (the Sanskrit word meaning the practice of “being un-hurtful,” the way of “harmlessness” or “non-violence”) is an ancient yoga practice. Patanjali, in his Yoga Sutras, around 2200 BCE wrote that “Refusal of violence, refusal of stealing, refusal of covetousness, with telling truth and continence, constitute the Rules” of the practice of Yoga. (1) A translator of the Yoga Sutras, Swami Purohit, commented that, “refusal of violence is love for all creatures.” In the text this sutra follows a discussion of karma, and the problem of an individual creating impediments to his liberation, as well as a discussion of the wisdom of avoiding the future misery entailed by actions of violence, a teaching, which is part of the beliefs about karma.

The Yoga Sutras text also states that, “When non-violence is firmly rooted, enmity ceases in the yogi’s presence.” (2) This ancient teaching reminds me of the last part of Gandhi’s life, when he traveled from village to village in parts of India where there were disturbances caused by communal conflicts. He had long before vowed to take the pacifist path, and his gentle presence inspired villagers to have faith in the power of nonviolence.

Read the rest of this article »

by B.D. Nageswara Rao

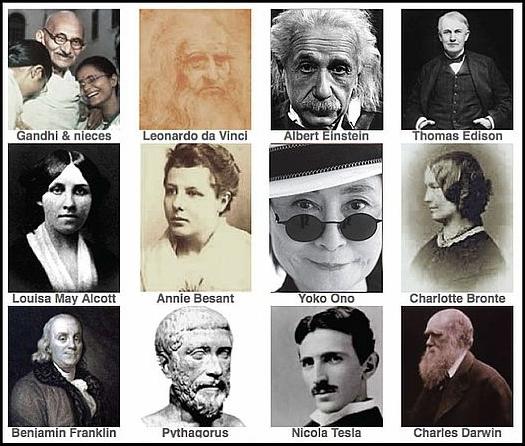

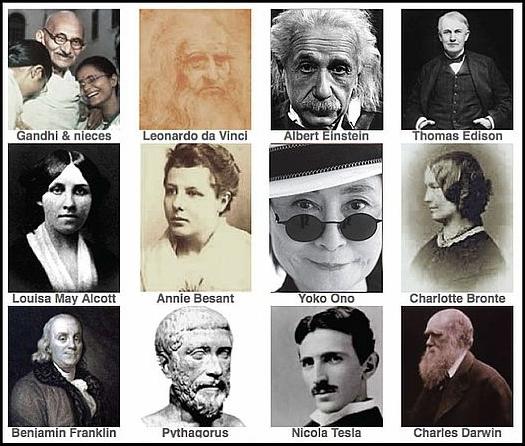

“Famous Vegetarians”; artist unknown; courtesy of herenow4you.net

Abstract

Gandhi’s message of nonviolence, and the methods he devised to practice it, are widely acclaimed to be of historical significance. However, his altruism seems contrary to the central tenet of Darwinism that survival is optimized for those who are adapted to the environment, i.e. those who are best prepared for war have the best chance of survival in a world where disputes are settled through violence. Nevertheless he chose nonviolence as an inviolable constraint in addressing all types of human problems and proclaimed, “While there are causes for which I am prepared to die, there is no cause for which I am prepared to kill.” His formulations of Salt Satyagraha, civil disobedience and non-cooperation movements are striking examples of profound analytical thought analogous (in my view) to Einstein’s formulation of the Special Theory of Relativity. Einstein was confronted with the experimentally proven fact that the velocity of light in vacuum is unchanged in a moving frame of reference. With this inviolable constraint he reformulated the laws of Newtonian mechanics by invoking a previously unthinkable requirement that mass, length and time change in a moving frame of reference, and thereby deduced the principle of mass-energy equivalence (E=mc2). Thus the Special Theory of Relativity was born, and a new era emerged in physics. Gandhi’s principle of nonviolence offered an alternative to war in solving global disputes, and thus ushered in a new era in human history. His message has influenced other reformers around the world, notably Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela. That it is not widely embraced is an indication of the fact that, functionally, human beings are basically driven by primitive Darwinian pressures generated by the reptilian brain, and have not allowed themselves to be persuaded adequately by the capabilities of the human brain which gave rise to ethics, altruism, and egalitarianism in our societies.

Read the rest of this article »