by Peter van den Dungen

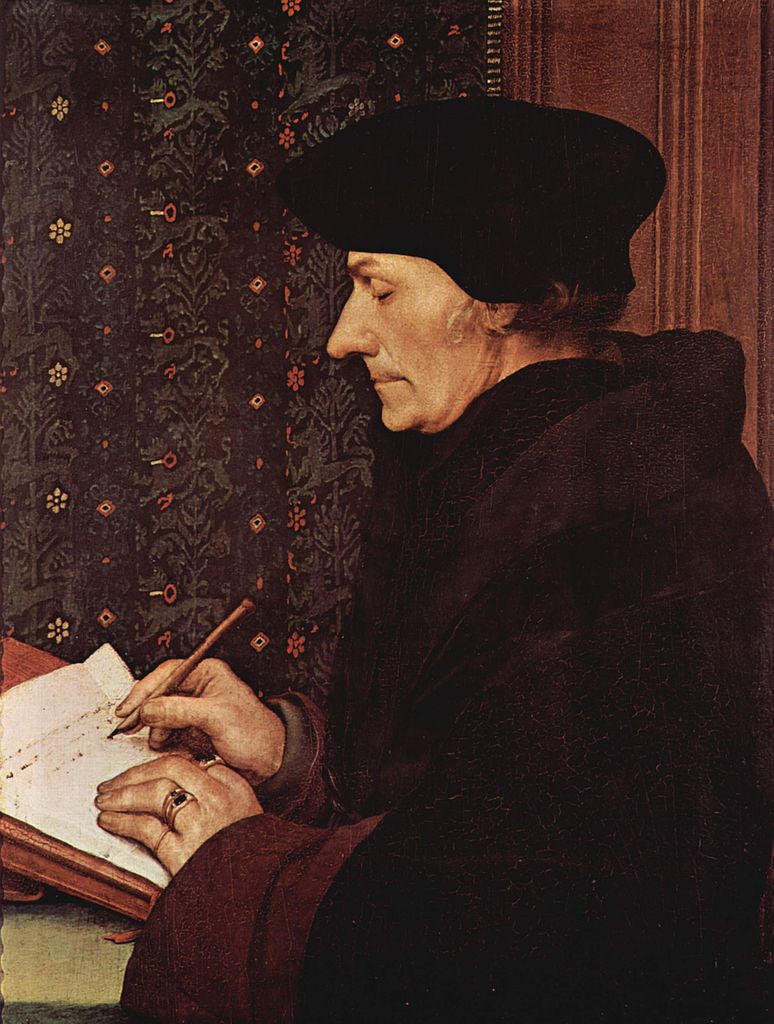

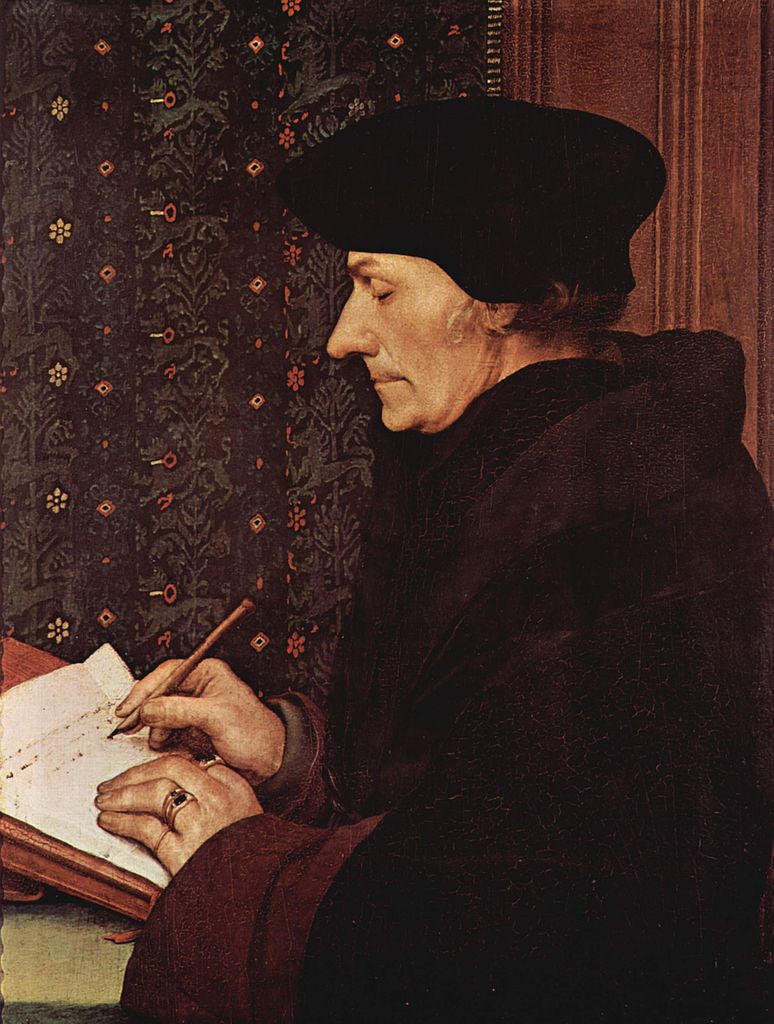

Erasmus, by Hans Holbein the Younger; courtesy of the Louvre

More than a century before Grotius wrote his famous work on international law, his countryman Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam laid the foundations for the modern critique of war. In several writings, especially those published in the period 1515-1517, the ‘prince of humanists’ brilliantly and devastatingly condemned war not only on Christian but also on secular/rational grounds. His graphic depiction of the miseries of war, together with his impassioned plea for its avoidance, remains unparalleled. Erasmus argued as a moralist and educator rather than as a political theorist or statesman. If any single individual in the modern world can be credited with ‘the invention of peace’, the honour belongs to Erasmus rather than Kant whose essay on perpetual peace was published nearly three centuries later.

Read the rest of this article »

by Narayan Desai

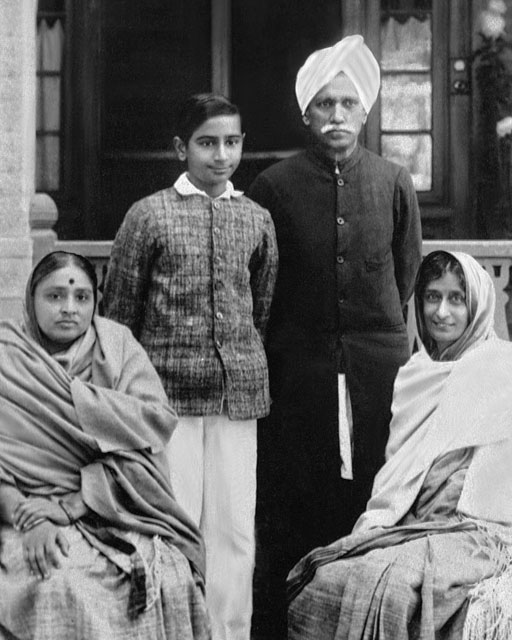

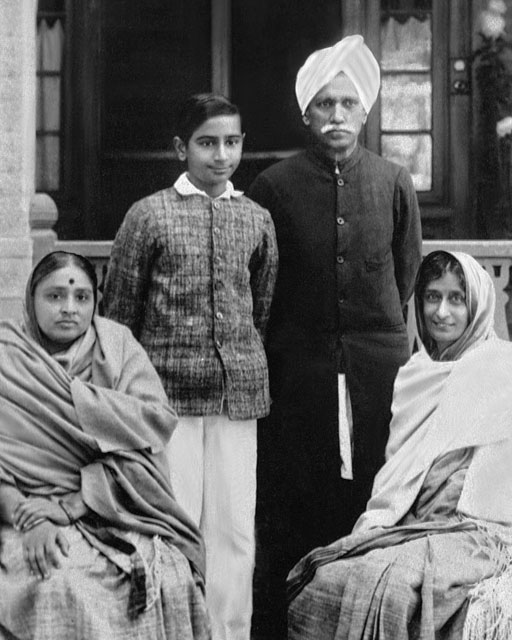

Editor’s Preface: Narayan Desai (b. 1924) is the son of Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s chief secretary until 1942. He is the founder of the nonviolence training center, the Institute for Total Revolution, and the author of a four volume biography of Gandhi among other works. He has been awarded both the Jamnalal Bajaj Award and the UNESCO Madanjeet Singh Prize for his work in nonviolence and pacifism. JG

Young Narayan Desai with parents; photo courtesy Narayan Desai

The Satyagraha Ashram of Mahatma Gandhi stood on the bank of the broad Sabarmati River, across from the city of Ahmedabad. “This is a good spot for my ashram,” Bapu used to say. All of us in the ashram called him Bapu, or Father. He added, “On one side is the cremation ground. On the other is the prison. The people in my ashram should have no fear of death, nor should they be strangers to imprisonment.” Indeed, my earliest memories of Bapu are intertwined with those of Sabarmati Prison. Bapu would go for a walk each morning and evening. He would put his hands on the shoulders of those to either side. These companions would be his “walking sticks.” We children were always given first choice for this job. Whether his human walking sticks were really any help to him, perhaps only Bapu could say. But as for us, being chosen always made us swell with pride. In fact, in our eagerness to be chosen Bapu’s “sticks”, we would sometimes clash.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mary Elizabeth King

Nonviolent struggle, also called civil resistance or nonviolent resistance is often misunderstood or goes unrecognized by diplomats, journalists, and pedagogues not trained in the technique of nonviolent action; to them, events ‘just happen’. To the contrary, however, nonviolent struggle requires that practitioners, who take deliberate and sustained action against a power, regime, policy, or system of oppression, consciously reject the use of violence in doing so. The technique of nonviolent action has been employed successfully in diverse conflicts—such as abolition of the trade in human cargo, establishment of trade unions and workers’ rights, voter enfranchisement, colonial rebellions and national independence movements, interstate strife, and religious conflicts—all without resort to violent measures, guerrilla warfare, or armed struggle. Mohandas K. Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. were emboldened by the collective nonviolent action of Africans in Ghana, Kenya, Zambia, and elsewhere, in the nationalist drive for independence. If violence is to be significantly reduced or abandoned in acute conflicts today, a realistic alternative must be presented, accepted, and understood. Contemplated in this article is the need for study, documentation, and teaching of nonviolent strategic action as a technique for securing justice that lends itself to a host of applications. As Gandhi and King learned from the African nonviolent struggles of their times, and relied on observations of African campaigns to improve their sharing of knowledge, so can the rest of today’s world.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mary Elizabeth King

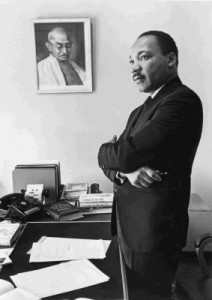

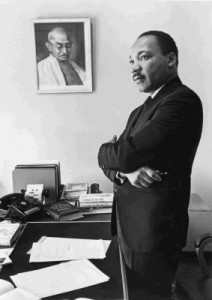

How does one learn nonviolent resistance? The same way that Martin Luther King Jr. did—by study, reading and interrogating seasoned tutors. King would eventually become the person most responsible for advancing and popularizing Gandhi’s ideas in the United States, by persuading black Americans to adapt the strategies used against British imperialism in India to their own struggles. Yet he was not the first to bring this knowledge from the subcontinent.

Martin Luther King, Jr. beside a picture of Gandhi; photograph © Bob Fitch

By the 1930s and 1940s, via ocean voyages and propeller airplanes, a constant flow of prominent black leaders was traveling to India. College presidents, professors, pastors and journalists journeyed to India to meet Gandhi and study how to forge mass struggle with nonviolent means. Returning to the United States, they wrote articles, preached, lectured and passed key documents from hand to hand for study by other black leaders. Historian Sudarshan Kapur has shown that the ideas of Gandhi were moving vigorously from India to the United States at that time, and the African American news media reported on the Indian independence struggle. Leaders in the black community talked about a “black Gandhi” for the United States. One woman called it “raising up a prophet,” which Kapur used as the title of his book.

While a student at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, King was intrigued by reading Thoreau and Gandhi, yet had not actually studied Gandhi in depth. A friend, J. Pius Barbour, remembered the young seminarian arguing on behalf of Gandhian methods with a reckoning based on arithmetic—that any minority would be outnumbered if it turned to a policy of violence—rather than on principle.

Read the rest of this article »

by Arne Naess

The combination of humility and militancy in emotionally charged social conflicts has always been rare. It is easy to succumb either to passivity or to verbal or nonverbal violence. Humility in confronting a human being, respect for the status of being a human being, whether that being is a torturer or a holy person, is essential.

People may be trained in nonviolent communication through sessions where they confront others with different attitudes and opinions. In schools and universities such sessions in the form of seminars, or otherwise, are easy to schedule. At the university level proposals of norms or principles of nonviolent communication help students to master conflict situations. From 1941 to around 1993, the set of principles formulated in this article has been used by about ninety thousand working in small groups at Norwegian universities. An emotionally charged topic is often selected, and the students asked to discuss it. Or they receive a written dialogue and are asked to analyze violations of the principles that will be outlined below.

Gandhi, the man, his deeds, and his writings have made such a profound impact on millions of people that it is felt all their lives, even if it does not always show up in social conflict activism. People’s veneration is serious and honest, but few have had, or even try to get, training to face opponents or “antagonists” in a Gandhian way.

The way Gandhi at times described the views of people who opposed him and his influence has made a lasting impression. One deed that struck me as glorious belongs to the area of the practice of communication. Instead of giving a broad historical account I shall describe one series of communications.

Read the rest of this article »

by Shinichi Yamamuro

“Philosopher’s Garden: Kyoto, Japan, 2012”; original photograph, by Michael Sawyer.

Non-violence often comes to mind when we think of the term ahimsa, which, for example, Gandhi used. The word himsa in Hindi means, “to inflict injury on a person,” in other words to hurt a person. The word ahimsa, “non-violence,” is formed by adding the negative adverb a. What exactly is “inflicting injury”? Naturally, it is easy to understand physical violence, such as war, in which people are harmed, but are there other ways of inflicting injury? If so, how should we understand non-violence?

Read the rest of this article »

by Dr. Saroj Kothari

Jain symbol; word ahimsa

within wheel of life; hand symbolizes vow;

courtesy commons.wikimedia.org

Violence and nonviolence

Today, all individuals, groups and nations are facing problems in one form or the other. Some of these problems are: psychological tension arising from economic inequity and the consumer culture; social problems and disintegration of society originating from conflicts of ideologies and faiths; political problems such as arms race, war and terrorism; and problems of human survival linked to production and ecological balance. The world is torn by tension, strife, crime and regional conflicts. Everybody is suffering from uncertainty about the future and lack of peace of mind. Many individuals, including social and political leaders, are trying to find solutions to their problems. They feel that scientific research and technological advances, nuclear weapons and improved war technology, consolidation of power and acquisition of material possessions, and concentrating on their own religious and ethnic groups will provide solutions to their problems. Religion emphasizes that peace of mind comes from tolerance and contentment. Morals and spiritual values including virtues such as nonviolence and truth can lead to genuine peace. However, to a large extent, these virtues are ignored on account of the glitter of materialism fueled by greed and the desire to get ahead of others. No doubt, scientific and technological advances have made human life, especially for those with material means, quite pleasant. Nevertheless, most people on earth have no peace of mind. In spiritual terms, one can say that we are living for the satisfaction of our animal instincts only. We do talk of higher moral, social and spiritual values but we fail to realize that material progress alone cannot lead to a resolution of conflicts arising from our selfish nature.

Read the rest of this article »