Statement of Purpose

Gandhi highly valued education as an essential part of his nonviolence program, and insisted it be included in the daily life of the various ashrams that he founded. If regular classes were held for children, adults were also asked to learn spinning, weaving, cloth making, and a host of other skills. It was not until 1909, however, that Gandhi began to systematize his thoughts, in Chapter 18 of one of his most important and influential works, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, which we have posted below.

by Helen Fox

Teaching Peace illustration courtesy johnworldpeace.com

Abstract: In-depth interviews with undergraduates at a high-ranking, politically liberal U.S. university suggest that young adults who are most likely to occupy future positions of influence are skeptical of the idea that a world without war is possible. Despite their aversion to war in general and the Iraq War (also called The Second Gulf War: 2003-2011) in particular, these students nearly always said they believe that war is an integral part of human nature and that peaceful international relations will always be subverted by individuals and/or groups that insist on taking advantage of others. When students defended the need for war, they did not cite international terrorism or self defense as just causes, but rather the responsibility to protect defenseless others such as villagers in Darfur or Jews in Hitler’s Germany. However, students knew little about the prevalence and efficacy of nonviolent movements or the range of diplomatic and political tactics that have been employed to deter violence. The author shares the content and methods of her seminar on nonviolence, and concludes that more courses in secondary schools and universities need to fill the gaps in students’ knowledge by teaching historical, social, political, and psychological information about both war and peaceful solutions to conflict.

Read the rest of this article »

by Paul J. Plumitallo

Dust wrapper art courtesy amazon.com

Paul J. Plumitallo: I was wondering what violence means to you? Can violence be more than physical? Is language ever violent? There have been some disagreements about what violence actually means in my class.

Kay Bueno de Mesquita: I believe that violence is more than physical. It can be internal as well as external: violence of the spirit, a range from psychological to emotional from mild to severe. The damaging words that someone can say can have a longer lasting harmful effect than physical violence.

Plumitallo: Do you consider yourself to be nonviolent? How does one apply nonviolent principles to their daily life? We often discuss how difficult nonviolence is in our society because we are so exposed to violence.

Bueno de Mesquita: It’s true that being nonviolent in all aspects of life can be difficult. In his first principle of nonviolence Martin Luther King Jr. states that, “Nonviolence is a way of life for courageous people.” [Please see the text of all Six Principles at the end of the interview.] Dr. King also said, “I’m not nonviolent some of the time, I’m nonviolent all of the time.” I strive to be nonviolent in every aspect of my life including thinking kind thoughts about myself, and others; being compassionate and empathetic to all people. I’m not always successful. But I try. I try to be mindful each day and “wake up each morning with a prayer and a smile.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Tom Gibian

Sandy Spring School, 2nd Grade Art Work; courtesy grover.ssfs.org/~ksantori/art/2nd_grade.htm

One of the underlying principles of Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence is our capacity for interconnectedness, or as Gandhi was to state it, “the interconnectedness of all beings.” Interconnectedness, or connecting, is also very much at the heart of Quaker concerns.

I remember being in third grade and having to line up and pair off with a classmate to walk down the hallway to some destination beyond our classroom. At Sherwood elementary school, there might have been 29 or 30 nine-year-olds and one teacher. On the day I’m recalling, I was paired off with a kid named Sammy. I was new at Sherwood and someone warned me that Sammy had sweaty palms. As we headed down the hallway, he took my hand. His hand was sweaty, but it didn’t matter. We held hands without embarrassment. We were not self-conscious. We were little, at least relative to the world we were living in, and it could not have been more natural to reach out, to partner, to connect. Later, Sam would be one of the first friends of mine to get a high-performance muscle car in high school. That is a different story!

Read the rest of this article »

by Devi Prasad

Schoolchildren dressing as Gandhi to commemorate his 146th birthday; courtesy newindianexpress.com

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished essay by Devi Prasad is another in our series from the IISG archive, Amsterdam. It is well to bear in mind that Prasad lived as a child at Tagore’s school, discussed in the article, and that he was later asked by Gandhi to teach in one of his ashrams. His knowledge of Gandhi’s education system, therefore, was uniquely first-hand. Please consult the notes at the end for archival reference, acknowledgments, and biographical information. JG

At the centre of Gandhi’s many concerns about social and political issues, there are two things that remained consistently predominant throughout his life. Firstly, a revolt against the education system that was given to, nay, imposed upon India by the colonial rule; and secondly, a powerful urge to find an appropriate approach and method of imparting education to all the children and adults of the country.

Read the rest of this article »

by Purushottama Bilimoria

Indian actor Bagadehalli Basavaraju poses in classrooms as living statue of Gandhi; courtesy thebetterindia.com

Mohandas Karamchand [Mahatma] Gandhi adopted the metaphysics of a broadly-conceived Hindu religious thought for his social critique, out of which he developed a distinctive educational philosophy, which gave particular emphasis to truth and nonviolence, or the teaching of peace. In his social thinking he gave immense importance to what he called a ‘balanced’ form of education. By this he meant balanced as to needs, i.e. the necessities of life, against wants, i.e. whatever one yearns to possess, acquire or enjoy out of desire; and, more significantly, balanced as to internal values against a disproportionate concern with the externals (1948: 52). By ‘externals’ is meant the goods people generate and the sorts of activities, planning and manoeuvres people carry out in the normal course of living in order to meet the demands of commerce, material accessories, personal welfare and reproduction, and which are at the same time instrumental in sustaining the community.

Read the rest of this article »

by Krishna Kumar

Gandhi poster courtesy izquotes.com

Rejection of the colonial education system, which the British administration had established in the early nineteenth century in India, was an important feature of the intellectual ferment generated by the struggle for freedom. Many eminent Indians, political leaders, social reformers and writers voiced this rejection. But no one rejected colonial education as sharply and as completely as Gandhi did, nor did anyone else put forward an alternative as radical as the one he proposed. Gandhi’s critique of colonial education was part of his overall critique of Western civilisation. Colonisation, including its educational agenda, was to Gandhi a negation of truth and nonviolence, the two values he held uppermost. The fact that Westerners had spent ‘all their energy, industry, and enterprise in plundering and destroying other races’ was evidence enough for Gandhi that Western civilisation was in a ‘sorry mess’. (1) Therefore, he thought, it could not possibly be a symbol of ‘progress’, or something worth imitating or transplanting in India.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mohandas K. Gandhi

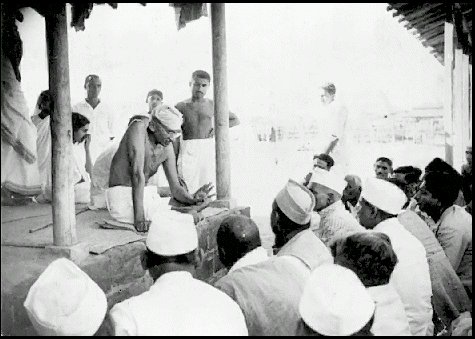

Gandhi teaching his followers; courtesy mkgandhi.org

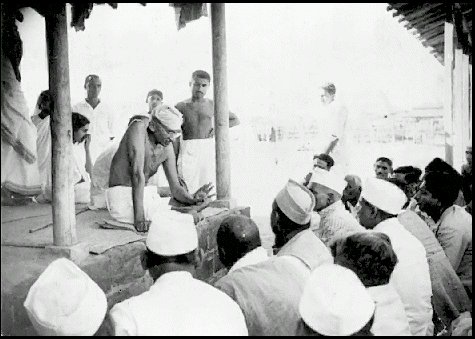

Editor’s Preface: Gandhi highly valued education as an essential part of his nonviolence program, and insisted it be included in the daily life of the various ashrams that he founded. (1) If regular classes were held for children, adults were also asked to learn spinning, weaving, cloth making, and a host of other skills. It was not until 1909, however, that Gandhi began to systematize his thoughts, in the essay that follows. It is, in fact, Chapter 18 of one of his most important and influential works, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, presented as a series of questions and answers between the fictitious, if sometimes obtuse “Reader”, and answers by a knowing “Editor”, both of whom, needless to say are Gandhi. Hind Swaraj was written in a flurry of work between 13 and 22 November 1909 while Gandhi was on board the Kilnonan Castle sailing back from England to South Africa. Although he continued to write about education in Young India, Indian Opinion, and other of the periodicals he edited, the text that follows is recognized as his first attempt to outline the basics of a curriculum consisting of language, Indian civilization, and ethics. Please consult the notes at the end for further bibliographical information. JG

Reader: In the whole of our discussion, you have not demonstrated the necessity for education; we always complain of its absence among us. We notice a movement for compulsory education in our country. The Maharaja Gaekwar has introduced it in his territories. (2) Every eye is directed towards them. We bless the Maharaja for it. Is all this effort then of no use?

Editor: If we consider our civilization to be the highest, I have regretfully to say that much of the effort you have described is of no use. The motive of the Maharaja and other great leaders who have been working in this direction is perfectly pure. They, therefore, undoubtedly deserve great praise. But we cannot conceal from ourselves the result that is likely to flow from their effort. What is the meaning of education? It simply means knowledge of letters. It is merely an instrument, and an instrument may be well used or abused. The same instrument that may be used to cure a patient may be used to take his life, and so may knowledge of letters. We daily observe that many men abuse it and very few make good use of it; and if this is a correct statement, we have proved that more harm has been done by it than good. (3)

Read the rest of this article »

by Dr. Abhay Bang

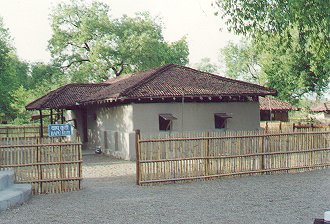

Sevagram Ashram, c. 1960s; courtesy mkgandhi.org

As a child growing up in the 1960s I went to an amazing school. Today, I feel helpless and sad because I’m unable to offer such an education to my son, Anand. “Our childhood was so different. Things have changed beyond recognition,” old timers often moan and groan about the past. Still, my heart is heavy. You may ask what was so different about my school?

From grades four to nine I studied in a school which followed Gandhi’s Basic Education tenets (Nai Taleem), located at Sevagram ashram in Wardha, founded by Gandhi in the 1930s. Education should not be confined within the four walls of the classroom mugging up boring subjects away from Mother Nature. Gandhiji’s Nai Taleem strongly believed that children learnt best by doing socially useful work in the lap of nature. This is how children’s minds would develop and they would imbibe a variety of useful skills. To implement such a system of education, the great poet and Nobel Prize winner, Rabindranath Tagore, at the behest of Gandhiji sent two brilliant teachers to Sevagram. Mr. Aryanakam came all the way from Sri Lanka and Mrs. Asha Devi from Bengal. This duo combined Gandhi’s educational methodology with Tagore’s love for nature and the arts. My parents, followers and friends of Gandhi, were involved with this educational experiment right from the start. The school tried out many novel experiments in education. Here, I will attempt to recall some of these.

Read the rest of this article »

by Don Lorenzo Milani

Don Milani with his students; courtesy www.giovaniemissione.it

Editor’s Preface: Don Lorenzo Milani (1923-1967) was born in Florence and became renowned as an educator of children from poor families, and an outspoken and controversial conscientious objector. His mother, Alice Weiss, was Jewish and a cousin of Edouardo Weiss, one of Freud’s earliest disciples. He was raised as an agnostic, but at the age of twenty he converted to Catholicism and was later ordained a priest. Besides his pacifist writing he also published in 1965, Letter to a Teacher (Lettera a una professoressa), which denounced the inequalities of class-based education systems “favouring the rich over the poor”. The book was in fact written cooperatively by Milani and eight student dropouts, and took a year to complete. It is considered one of the great Italian pedagogical works. In this book and in his classes he insisted on teaching conscientious objection, or what he termed “going against the grain” history. A useful article about Milani may be found at this link. JG

Introduction by Devi Prasad [1965]

Don Milani is an outspoken and intellectual person with deep political understanding. He is a parish priest and lives in Barbiana nearly 50 kilometres north of Florence, a place in the hills not easily accessible. When I went to meet him last August I felt it could not have been just chance that a priest like Don Milani is placed in such an isolated village. I later learnt that Church authorities sent him there after the publication of his book Pastoral Experience. He is perhaps too dangerous to be allowed to live in a central place where many more people can come in contact with him.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jean-Marie Muller

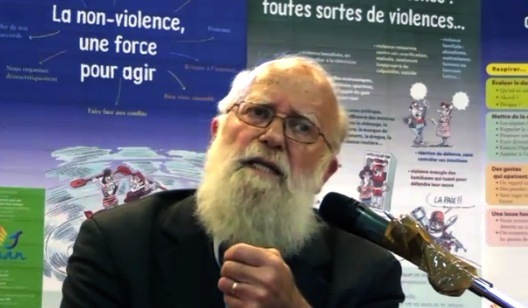

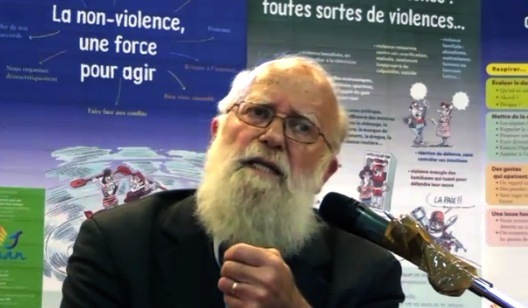

Photo, Jean-Marie Muller; courtesy histoiresordinaires.fr

On 10 November 1998, the General Assembly of the United Nations proclaimed the period 2001–2010 “the International Decade for a Culture of Peace and Nonviolence for the Children of the World” (Resolution 53/25). The General Assembly considered that “a culture of peace and nonviolence promotes respect for the life and dignity of every human being without prejudice or discrimination of any kind.” It furthermore recognised the role of education “in constructing a culture of peace and nonviolence, in particular the teaching of the practice of peace and nonviolence to children, which will promote the purposes and principles embodied in the Charter of the United Nations.” The General Assembly went on to invite member states to “take the necessary steps to ensure that the practice of peace and nonviolence is taught at all levels in their respective societies, including in educational institutions.” There may well be good reason to celebrate the fact that the representatives of the member states assembled in New York voted for such a resolution, but nonviolence is still alien to the culture we have inherited. The core concepts around which our thought is organised and structured leave little room for the idea of nonviolence; violence, on the other hand, is inherent in our thinking and behaviour. Nonviolence is unexplored territory. Our minds have such trouble grasping the concept of nonviolence that we are often inclined to deny its relevance. So a great deal of educational work remains to be done to prevent the United Nations resolution from going unheeded, and to ensure that the “culture of peace and nonviolence” to which it refers really does change the mindset of teachers and children.

Read the rest of this article »