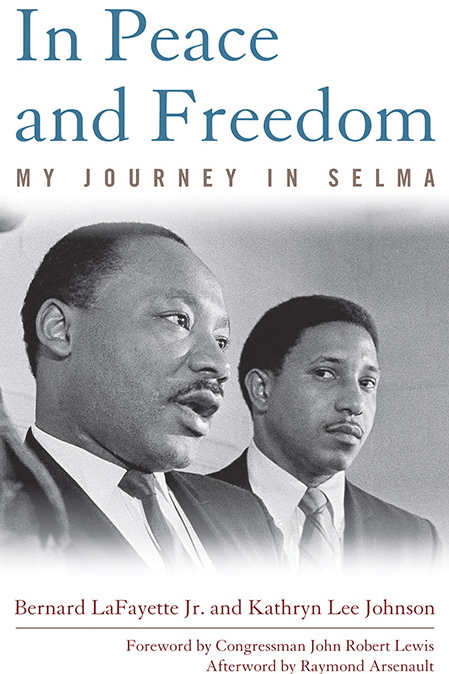

John Lewis and the Spirit of Selma

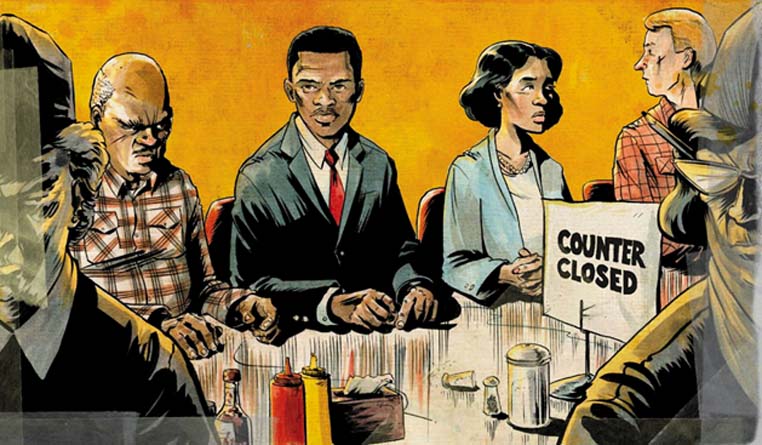

John Lewis at Nashville sit-in, book cover of March: Book One, courtesy topshelfcomix.com

Editor’s Preface: John Robert Lewis (b. 1940) is the U.S. Representative for Georgia’s 5th congressional district, and the dean of the Georgia congressional delegation. His district also includes the northern three-quarters of Atlanta. His Wikipedia page is a reliable starting point for information about his nonviolent civil rights activities and his political career. JG

It has now been 50 years since “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama, when John Lewis and Hosea Williams led some 600 civil rights marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7, 1965. The demonstrators attempted to march peacefully from Selma to Montgomery in support of voting rights, but state and local police viciously attacked the nonviolent procession, brutally beating them with whips and clubs, firing tear gas and charging the defenseless marchers on horseback. Hundreds of people suffered bloody beatings and some were clubbed nearly to death.