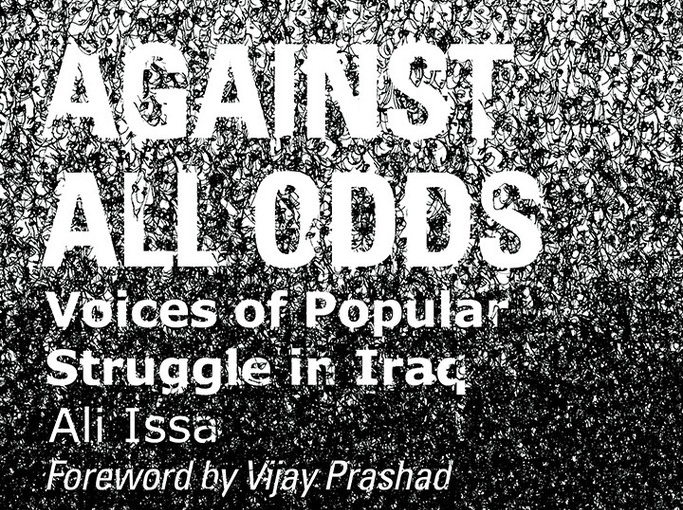

Book Review: Against All Odds; The Iraqi Nonviolent Movement

by Judith Mahoney Pasternak

Book jacket art courtesy tadweenpublishing.com

If you follow the Western media, the news from Iraq is almost always bad. A quarter century of war, including 13 years of brutal sanctions, invasion, a no less brutal eight-year occupation, an externally imposed, undemocratic and repressive government, and now the attempt by the Islamic State to remake Iraq in its image — all have resulted in millions of deaths, and the toll keeps rising. “Such a bruised country! No society can withstand such pressure,” declares Indian journalist Vijay Prashad in his foreword to Against All Odds: Voices of Popular Struggle in Iraq [Washington, D.C. and Beirut: Tadween Publishing, 2015].

Yet there is another side to the story of Iraq, one that has been rendered all but invisible in the media, which seem to have no room for the words “hope” and “Iraq” in the same sentence. In February of 2011, in the wake of the Arab Spring, the hunger for a better future for Iraq — a hunger that had been repressed but never suppressed — arose again in force in cities across the ravaged country, in the form of a decentralized mass nonviolent protest movement. Against All Odds is the story of that movement, told in part by War Resisters League organizer and writer Ali Issa, and in part by eight leaders of different segments of that movement.