Stephen Zunes On A Power That Can Overthrow Dictatorships

Nonviolent movements have toppled dictators all over the globe, in Mali, Serbia, Poland, Bolivia, the Philippines, East Germany, Latin America, and Africa. During the Arab Spring, it became clear that the power of nonviolence to overthrow tyrannical governments is giving new hope — and new revolutionary strategies — to people around the world. Just as several unexpected and massive nonviolent uprisings have dealt serious blows to brutal regimes around the globe, several scholars and researchers have dealt equally serious blows to generations of military analysts and national-security studies.

In a pioneering effort to systematically compare success rates of violent and nonviolent social-change movements, Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, authors of Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, researched 323 social-change campaigns from 1900 to 2006. Their electrifying finding was that campaigns of nonviolent resistance are nearly twice as likely to succeed as violent uprisings.

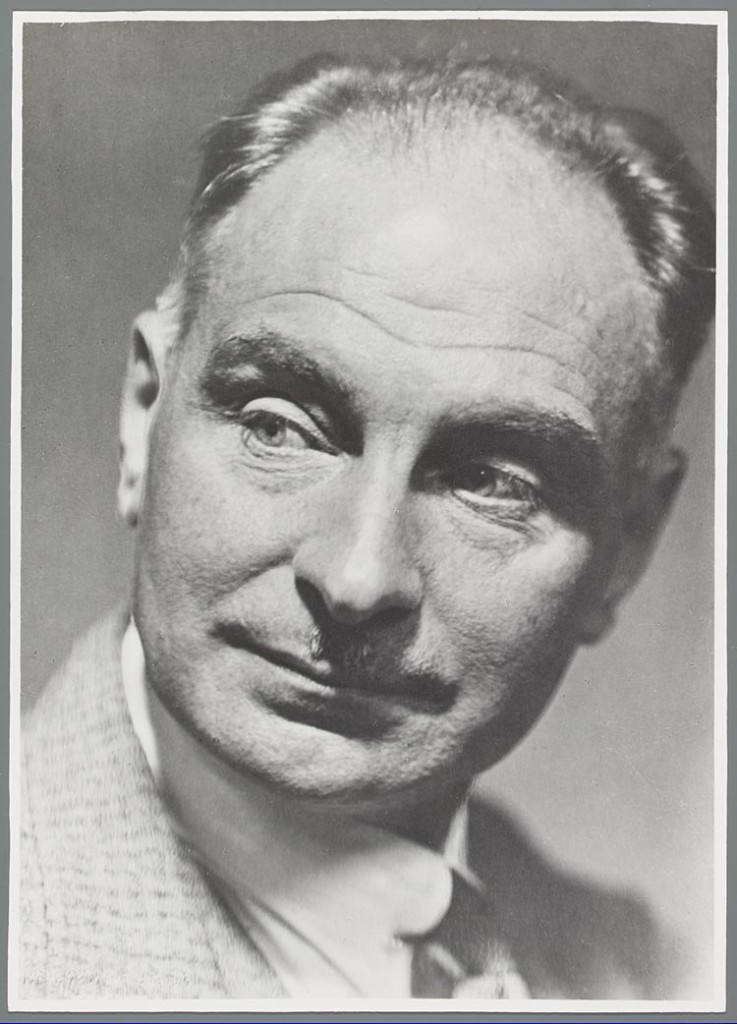

Stephen Zunes c. 2012; photographer unknown

Their innovative research may have proven astonishing in the circles of international security and military analysts, but it was solid confirmation of the lifelong research into nonviolent resistance carried out by Stephen Zunes, an author and Professor of Politics and International Studies at the University of San Francisco. Zunes’s parents were active in the peace movement. His father was an Episcopal priest and his parents were involved, along with many Quaker peace groups, in challenging U.S. militarism. He grew up in a Christian milieu where there was a strong sense of individual commitment to peace and social justice. He then attended Quaker schools and later worked with a number of Quaker peace groups, including the Friends Peace Committee and the American Friends Service Committee. Yet, his scholarly research, writing and teaching about the history of nonviolent movements was sparked, in part, by his realization that the strategies and tactics of nonviolent resistance not only had value for principled pacifists, but also could be utilized as a pragmatic — and highly effective — approach to social change by people from all walks of life, no matter their ideology or belief system.

In an interview with Street Spirit, Zunes said, “In terms of nonviolence, I realized one can’t build a movement just by calling on people to embrace pacifism. But if people recognize the utilitarian advantages of nonviolent action, it would help build the kind of movement that could create real change. So, academically, I got very interested in studying the phenomenon of strategic nonviolent actions.”