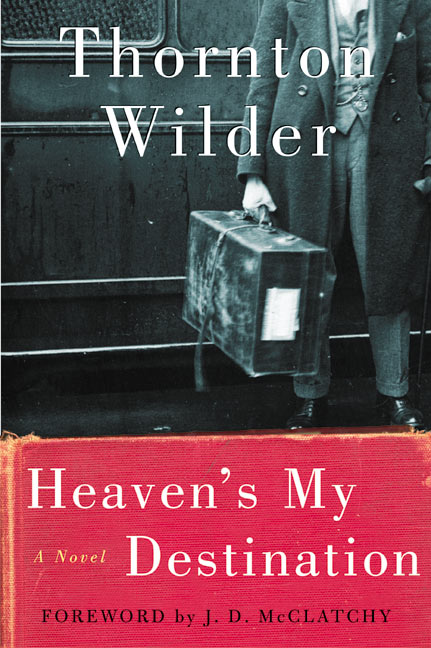

Book Review: Thornton Wilder’s “Gandhian” Novel, Heaven’s My Destination

Thornton Wilder published Heaven’s My Destination in 1935, seven years after winning the Pulitzer Prize for The Bridge of San Luis Rey. The main character, George Brush, is a Depression-era twenty-three year old. He is a socially awkward naïf; he seems a simpleton to most people he meets. A traveling salesman, evangelist, and pacifist, he is at odds with general American sentiment regarding such things as money and worldly success, and he gets in trouble for proclaiming religious statements in public, often writing them on hotel desk blotters.

The mishaps of this misfit, his miss-steps, mistakes and misunderstandings repeatedly cause him discomfort. He is a kind of American Candide, a Don Quixote, or a Kafkaesque bumbler who never quite sees why his extreme idealism puts off so many people. Yet Brush is quite successful at selling schoolbooks, and he has a great singing voice, so he appears attractive to some people some of the time. But as soon as he begins talking about his theories and beliefs he loses people’s sympathy.

Thornton Wilder once wrote that “Art is confession; art is the secret told.” What is the “secret” expressed in the story of Heaven’s My Destination? I would suggest it is that humanity is disappointingly cynical, and our faiths only roughly approximate higher principals; they are not perfect guides, which we can force others to accept as their own. The implications of this open secret for learning as we go through life, for finding a viable path, are profound. I think this book written nearly eight decades ago tells a fable still valuable in our time, which has its own extremists. By depicting the curious antics of an extremist, it shows us what it takes to make a “true believer” begin to take idealistic teachings with a grain of practical salt. It shows that it is not wise to be too vehement in inflicting our doctrines on others, and that literalism is dangerous, causing nice people to act like fanatics.

Brush’s problem could be thought of as a conflict of age and youth: being a young man with an old-fashioned mind-set. For example, the ideas of evolution (which include human beings evolving from apes), and the new-fangled practice (in the Depression era) of American women smoking cigarettes, make him feel that the world-as-it-should-be is in danger of ruin. To people around him who are savvy, such naiveté seems sappy. Though he’s college-educated, Brush seems out of touch, a fool. But on the other hand, he’s often just taking seriously what all the hypocritical people say they believe. His sensitive conscience throughout the story is struggling to do what is right in a world he never seems able to please. He is almost Kafkaesque in experiencing the dissonance between his view and the average person’s views. He seems out of step with the time in which he lives.

George Brush’s “vow of poverty” is out of tune with the modern American mindset. Renunciation is a high ideal from earlier times and places, in India, as well as in medieval Europe. Christian monks abandoned the world, lived secluded in monasteries, and foreswore belongings. The 19th century American folk saint John Chapman (Johnny Appleseed) is remembered as someone living a life of renunciation; so is Henry David Thoreau. In the 20th century, Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day, founders of The Catholic Worker movement, tried to eschew luxuries and serve the poor. Their appreciation of a life of poverty and simplicity has deep roots. The bible teaches believers not to gather treasures on earth where moth and rust corrupt, for example. But when a successful salesman like George Brush takes a vow of poverty, naturally his contemporaries see it as ill-suited to the time and place, hustling bustling 20th century America. His odd encounters with everyday people on Main Streets reminded me of a novel, A Naked Man, by Michael Tobias, about someone who gives his clothes to a homeless man in modern Los Angeles, then wanders naked like a Jain Digambara monk of India. George Brush, radical as a mini-Gandhi, finds that even in the middle of the Great Depression, America is a buzzing, blooming, hard-nosed businesslike place, and his friends urge him to be more down to earth.

Likewise he is always out of sorts with the women in his life. He may have a great singing voice and be attractive enough physically, but all his hopes and highest expectations for a wife and kids, and his dreams of enjoying being home for Sunday after-church dinner table feasts seem doomed because things never turn out as he imagines they should. He cannot seem to accomplish his version of the American Dream. When, after finding the woman he once slept with and then lost track of, he tries to become the husband and father of his dreams, it ends mostly in failure. “Nobody lives up to the rules,” he is told. And after swallowing that bitter failure pill he buys a pipe and begins to smoke it. He begins to change. Maybe the change is toward a more grounded soulfulness, instead of an overly idealistic perfection-in-the-sky vision.

The sources of George Brush’s ideas include Christian teachings such as the Sermon on the Mount, and the life and teachings of Gandhi. Gandhi is mentioned several times in the book. Brush followed Gandhi’s path in his money dealings, in his periods of fasting and silence, and in his philosophy about how to treat those who try to rob or harm people. His philosophy is more like “turn the other cheek” than “defend yourself and get revenge.” The Sanskrit term “Ahimsa” is mentioned more than once in the story, without being defined much, so the word must have been somewhat familiar to Americans in the mid-1930s because of Gandhi’s fame. Brush, as he traveled around America in his work, was experimenting with ways that might cause criminals to turn over a new leaf. It is a sincere mimicking of the teachings of Gandhi and Jesus. Those who take the Sermon on the Mount seriously look at the world differently. Ahimsa, meaning “do no harm” or non-violence, almost seems a lost art. To accept suffering instead of fighting back is a method used by Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., to appeal to the conscience of a belligerent oppressor. At the time that Thornton Wilder wrote this novel, India had not achieved independence by using this method, and the Civil Rights movement in America had not yet made great strides by means of these principles. Perhaps Brush was an “early clue to the new direction,” seen in the light of those later events. He seemed absurd, but he was on to something; he was a misunderstood failure, yes, but more mature people such as Gandhi and King would make much social progress using some of the same ideas he was trying to practice.

The sayings of Leo Tolstoy also inspire Brush. When he tells a more jaundiced man he is inspired by Tolstoy he is told that those writings are “poetical”—and should not be taken to be like the actual facts of life. He is told that Tolstoy’s and Gandhi’s ideas are based on a profound misunderstanding of the criminal mind. The judge who tries him when he is on trial for a misunderstanding, has sympathy for him though, and cautions him, “Go slow; go slow… The human race is pretty stupid… Go gradual… Most people don’t like ideas.” (John Lennon, in a song about imagining a world at peace, sang, “You may say that I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one.” And Lennon, like Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., died of an assassin’s bullets.)

Both Christianity and Buddhism offer transmitted wisdom about non-violence in teachings which often sound absurd to more cynical worldly-minded people. Yet, inspiring many people for many centuries, Buddhism and Christianity at their best spread widely among diverse populations and kindled much compassion and non-violence. Of course, there are plenty of historical examples where those teachings have been forgotten, too. But teachings of compassion and non-violence serve a social purpose that is civilizing.

Heaven’s My Destination is gracefully narrated, with simplicity and fast-paced adventures through a variety of American locales and situations. I think it is a wise book, depicting the spirit of youth, the archetype of the puer aeternus, like the Chinese classic I Ching hexagram-change “Youthful Folly”(meng). The simple-minded enthusiastic youth acts in naïve exuberance, and experiences a disillusioning. By the end of the tale Brush’s hopes and dreams are demolished, as he reaches his twenty-fourth birthday. He is no longer so zealous, yet with scaled-down endeavors he continues to help others.

Thus, the story enacts a clarification in which a haze of wishful thinking is dissolved by the rude awakenings and hard knocks of realizing that life is more complicated than any theology or ideology. The unfolding of the story enacts a kind of modern age initiation rite, or an ordeal by fire and disappointment. The fool/pilgrim survives the journey, but along the way he loses some of the illusions he has been clinging to. For example, near the end, Brush meets a girl who believes in Darwin’s findings about evolution. Now, instead of trying to make her change her views, as he would have done before, he pays for her to go to college and study science.

There is a saying by Blake: “If a fool would persist in his folly he would become wise.” George Brush does that, he sticks to his beliefs, eventually suffers wretched disappointments and becomes very ill, then he carries on, good-hearted but less foolish than before. Experiences of the world have smoothed his rough edges, and the outsider begins to belong. Education is an initiation. To be wise is to be not overly sweet and Pollyanna-ish and also to be not overly bitter and hopeless. It is a sensible balance, a life-supportive harmony.

As Plato and Lao Tzu said, “It is better to think you don’t know when you do know, than to think you know, when you don’t.” Youthful folly experiments and arrives at unexpected letdowns, and through sufferings of love finally begins to get it right.

I would like to conclude this review on a personal note. First, I’m happy to recall that I knew Thornton Wilder’s older brother Amos. He was a respected poet, and when I arrived to study world religions at Harvard Divinity School, Amos hosted poetry readings at his home, and I read one of my poems there, and enjoyed his discussion of the poems we all read that night. Amos was a friend of my teacher in graduate school, J.L. Mehta, some of whose essays I collected in a book I edited and introduced, J. L. Mehta on Heidegger, Hermeneutics and Indian Tradition. Amos Wilder shared the artistic flair and intellectual power that his brother Thornton was blessed with, and I feel fortunate to have met him.

Second, it’s an interesting coincidence that the name George Brush is similar to George Bush. I remember when George W. Bush became president I thought “He is going to get an incredible education as president.” I pictured not only his cabinet, team of advisers, and briefers teaching him, but also experiences I thought he would have in encountering all the aspects of the world he had no clue about—how humbling that would be, how the scale of constant complex issues to face during those years would inevitably be a source of growth for any person in that position. But I was surprised by what happened. I was naive to assume it would be an education. If one blindly follows an ideology, has no curiosity, and lives in a bubble that excludes encounters with the actual elements of learning, one will not learn. That is a hard stance of the psyche for me to imagine, especially from a distance. (Coincidentally a character in Heaven’s My Destination mistakes the hero’s name for George Bush.) But the novel character George Brush came to understand that life is a teacher beyond simple-minded ideology. Thus he represents a true pilgrim.

Unless we are here to learn as we travel along, what’s the point?

EDITOR’S NOTE: William J. Jackson is professor emeritus of religious studies at Indiana University-Purdue University. He was the first Lake Scholar (2005-2008) at the Lake Family Institute on Faith and Giving, Philanthropic Studies Center, Indiana-Purdue University. His academic specialties are the comparative study of religion, Asian arts and literature, South Indian bhakti (devotion) in the lives and works of singer-saints. He is also an authority on Fractal Geometry in the Humanities, that is, recursive patterns in music, literature, art, and architecture. His awards include a Research Fellow, Bellagio, Italy Research Center Rockefeller Foundation, 2000; and Contemplative Practice Fellowship Program, American Council of Learned Societies, 2000. His most recent book is a novel, Gypsy Escapades, published by Rupa Publications in India. His article, “Gandhi’s Art: Using Non-Violence to Transform Evil” appeared 20 November 2012 on this site. Further information about Dr. Jackson is available on Indiana University’s website.