Book Review: My Life is My Message by Narayan Desai.

by Orient BlackSwan

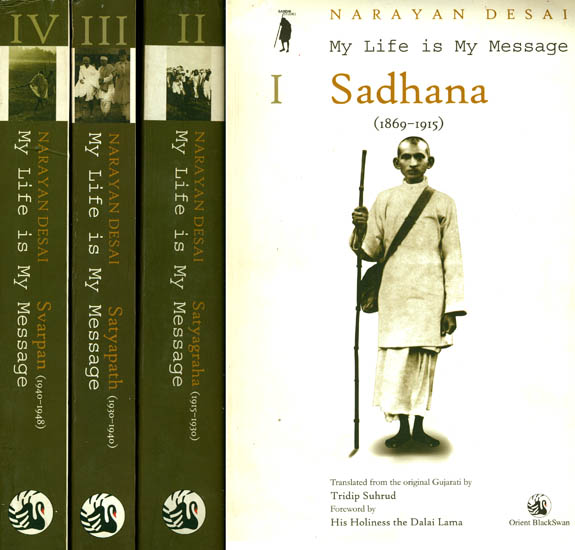

Cover art courtesy orientblackswan.com

Editor’s Preface: Narayan Desai (b. 1924) was the son of Gandhi’s personal secretary and closest advisor, Mahadev Desai. Raised and educated at Gandhi’s ashrams, Sabarmati and Sevagram, he has remained committed to the Gandhian movement and to Gandhian principles his entire life. After marrying he joined Vinoba Bhave’s community and later became a leading figure in the Shanti Sena, Peace Army. He founded Peace Brigades International, and was also chairman of War Resisters International. This four-volume biography of Gandhi, written in Gujarati, has long been considered a staple of Gandhian research and this first English translation is a welcome addition to the literature. The text that follows is the publisher’s description of My Life is My Message (tr. Tridip Suhrud), 4 vols., Gandhi Studies (New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2009). Please consult the Editor’s Note at the end of the article for further information. JG

Most biographies of Mahatma Gandhi tell the story of a great political leader who led India to freedom. But for Gandhi, his politics was a part of his spiritual quest. Swaraj means self-rule and not merely political autonomy; Gandhi’s struggles were meant to aid the quest for individual self-perfection. Everything he did—the Dandi salt march or his fasts for self-purification—was part of this struggle for self-realisation.

Narayan Desai’s epic four-volume biography was published in Gujarati as Maru Jivan Ej Mari Vani (My Life is My Message), and has long been hailed as one of the finest insights into the life of Gandhi. Desai describes Gandhi’s quest as one indivisible whole, in which “the political” is not separate from “the spiritual”. My Life is My Message liberates the Gandhi story from the constraining tyranny of political discourse and gives centre stage to his “soul-searching”. The struggle both within and without are seen as aspects of the same undivided reality, just as the inner journey of the self is depicted as an interaction with the life of the collective. What emerges is a complete picture of Gandhi.

Drawing from a wealth of original sources (what Gandhi wrote in letters, books and newspapers, spoke in intimate conversations with his fellow “servant co-workers”, in speeches and interviews, and what those around him wrote and spoke about him), the narrative is illuminated, above all, by Narayan Desai’s own life as an inveterate Gandhijan since his childhood years in Gandhi’s ashrams.

Volume I, Sadhana (Spiritual Practice) deals with the first 45 years of Gandhi’s life (1869-1914) a fascinating story of how a shy Indian student of average intelligence, through a London education becomes the lawyer of the Indian community in South Africa who will lead thousands of indentured labourers in their struggle for dignity. Beginning with serving his parents, he goes on to serve the cause of vegetarianism and, later, that of the Indians in South Africa. Through “humble homage and service and by repeated questioning,” he masters the knowledge of truth, worships it, and then experiments with its immense force by forging the weapon of satyagraha. From a pledge taken before leaving Indian shores for the first time, not to touch “meat, wine and women,” to deciding in the waiting room at the Pietermaritzburg station to suffer but not to leave the country like a coward, Gandhi will mark every major change in his life with a vow. Volume I also contains intimate portraits of close associates, of the founding of the journal Indian Opinion, and of life in Gandhi’s first ashrams, Phoenix and Tolstoy farms. It is a story that spans three continents.

Volume II, Satyagraha (Truth/Soul-force) records the sixteen years following Gandhi’s return to India from South Africa, that is from 1915 to 1931. These are the years in which he implemented in his home country the political, social and spiritual experiments that he had been formulating in South Africa. His interactions with moderate and extremist Indian leaders, with Hindu, Muslim and other religious groups, and with the British, make for riveting reading. Gandhi becomes the central figure influencing an entire generation of Indians during this eventful period of Indian history, when the country witnessed the Champaran movement, the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre, the Khilafat movement, Non-cooperation movement, satyagrahas at Ahmedabad, Kheda, Bardoli, Vykom, Dandi and other places, and instances of both unity and discord between Hindus and Muslims. This volume chronicles Gandhi’s relationships with Ranindranath Tagore, the Ali Brothers, the Nehrus, Jinnah, Mirabehn, Maganlal Gandhi, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and countless others. Above all, the book gives us an insight into the Gandhian way of life—his ashrams, his belief in the charkha and khadi, and the evolution of Gandhi’s thinking into the constructive programmes that he initiated and inspired. Prolific writing, fasts, imprisonments, illness and experiments with food also marked this period of Gandhi’s life. It is a life lived intensely and passionately, conscious of its commitment to truth and nonviolence.

Volume III, Satyapath (Right Path) covers the years 1930 to 1940, a period of intense dialogue in Gandhi’s life. It begins with Gandhi’s trip to Europe to participate in the Second Round Table Conference and deals with his immensely rich dialogue with the people of England and with European intellectuals such as Romain Rolland. Gandhi’s subsequent imprisonment and his fast against the Communal Award lead us to his dialogues with Dr. Ambedkar and the Harijan Yatra. The volume provides a moving account of Gandhi’s fast for self-purification and explores his relationships with Subhas Chandra Bose, the Socialists, Vinoba Bhave, Charlie Andrews and Herman Kallenbach. It also provides a detailed analysis of Gandhi’s “Constructive Work”. The narration guides us to the last and most moving phase of Gandhi’s life, which would commence with the Quit India movement.

Volume IV, Svarpan (Self-sacrifice) focuses on the last phase of Gandhi’s life (1940-1948). It begins with the failure of the Cripps Mission and Gandhi’s call for the “complete and immediate orderly withdrawal of the British from India,” thereby launching one of the largest non-violent civil disobedience movements, the Quit India Movement. It offers poignant glimpses into the lives of Gandhi and his associates inside the Aga Khan Palace Prison, as well as the deaths of Kasturba and of his beloved secretary and confidant, Mahadev Desai. Moving on to the complex negotiations between Gandhi, the INC and the British government following the release of the Congress leaders, the author provides clear insights into the different and, at times, clashing personalities involved. There is an incisive account of the emergence of Jinnah on the political scene, his subsequent rise as the leader of the Muslim League, and the demand for Pakistan. Svarpan covers Gandhi’s last journey through Noakhali, Bihar and Calcutta, and the miracle of non-violence this lonely pilgrim sought to bring about. The last few chapters describe his last day in detail, until the fateful moment on January 28, 1948, when Nathuram Godse pulled the trigger. The book ends with a discussion on the relevance of Gandhi today, in the 21st century.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Besides the information contained in the Editor’s Preface, we might also note that Narayan Desai worked alongside his father from 1936–46 as Gandhi’s secretary. He joined Vinoba Bhave’s Bhoodan movement 1952–60, and Jayaprakash Narayan’s movement from 1960–76. He has written over 50 books in Gujarati, Hindi and English. His awards are too many to list in full, but we might mention the Ranajitram Gold medal (highest literary award in Gujarati), the Jamnalal Bajaj Award for constructive work and UNESCO Award for Nonviolence and Tolerance. He is Chancellor of the Gujarat Vidyapeeth, founded by Gandhi in 1920, and President of the Gujarati Sahitya Parishad.

The translator Tridip Suhrud is a political scientist and a cultural historian specializing in the Gandhian intellectual tradition and the social history of Gujarat of the 19th and 20th centuries. He has translated the works of Ashis Nandy and Ganesh Devy into Gujarati and novelist Suresh Joshi into English. Among his translation are, C.B. Dalal’s Harilal Gandhi: A Life (Orient BlackSwan, 2007). His own books include Writing Life: Three Gujarati Thinkers (Orient BlackSwan, 2008). He is at work (with Suresh Sharma) on a bilingual critical edition of Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj (Orient BlackSwan). He is currently professor at Dhirubhai Ambani Institute of Information and Communication Technology, Gandhinagar, India. This article courtesy of Ganesh Subramanian, Executive Rights and Permssions Editor, and Orient BlackSwan Books.