Bart de Ligt (1883-1938): Non-Violent Anarcho-Pacifist

by Peter van den Dungen

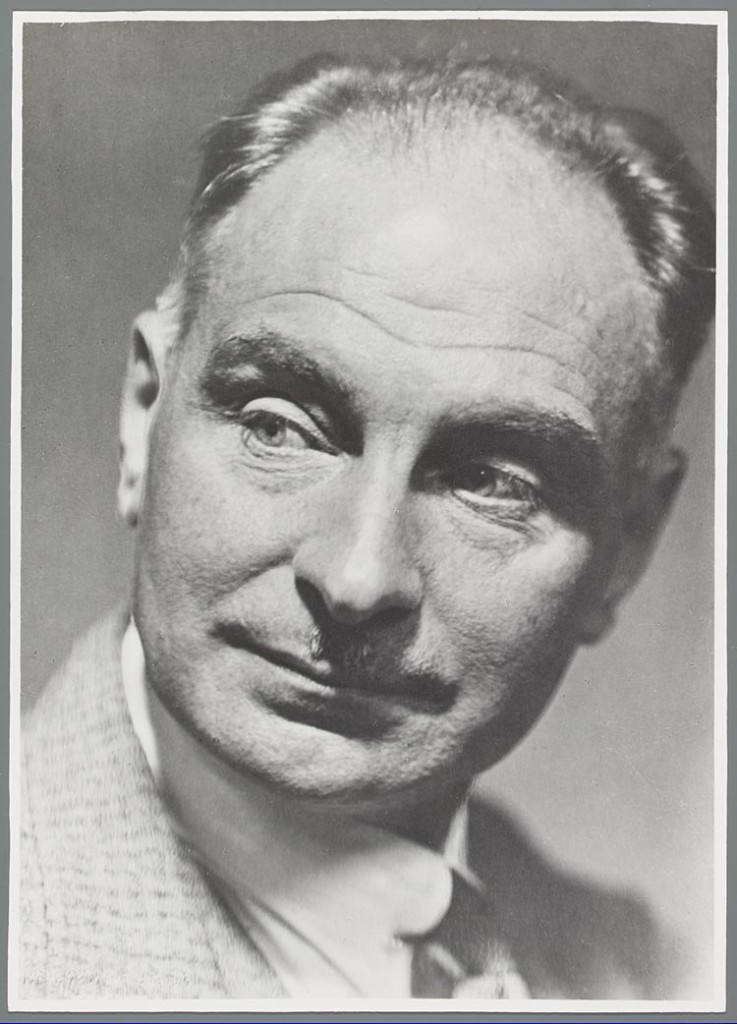

Bart de Ligt c. 1935; Public domain image; photographer unknown; courtesy of International Institute for Social History.

On 3 September 1938, within a year of the publication of The Conquest of Violence (his only book translated into English), Bart de Ligt collapsed and died in the railway station at Nantes. He had been taken ill in Bretagne and was on his way home to Geneva. Only 55, he had led such an intensively active public life, fully dedicated to the struggle for a better society, that this time his exhaustion proved to be fatal. His wife, who was his close collaborator, said that his life was like a flame, which had been extinguished too soon. But it had been a brilliant flame which had illuminated the thoughts, warmed the feelings, and lit or fanned the fervour of all those who had the good fortune to come into contact with him either directly through his countless public lectures, speeches and organisational activities, or indirectly through his equally numerous publications. It may be regarded as symbolic that he died in Nantes, the city where Henry IV signed the Edict granting freedom of conscience and worship to the French Protestants (who had been killed in their thousands in the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572 and afterwards), for de Ligt was a fighter of all dogma, whether religious or secular, and a fearless defender of all those who, in the past as in his own day, were branded heretics. Being a chief among them, he conducted his own kind of inquisition which was one relentless exposition of, and opposition to attitudes, practices and institutions which resulted in the enslavement of the individual and the establishment of a society which was far from truly human.

Who was this iconoclast who likeminded contemporaries regarded as a ‘superior spirit’ and an ‘exceptional figure’ in Dutch intellectual life? The relatively few people, then as now, in Holland and abroad, who know and admire de Ligt’s social philosophy and social action – against war and all the things which make for war – saw him as a figure bearing comparison with Erasmus, whom he resembled in several ways, and whose biography, published in Dutch in 1936, was his last book.

Bart de Ligt was born on 17 July 1883 in Schalkwijk near Utrecht, the son of a Calvinist pastor.(1) Against the dogmatic religiosity of his father, he underwent from an early age the beneficial religious influence of his mother, who inspired him with stories from the Bible, and to whom he later attributed his love both for the prophetic and Utopian, and for the cause of feminism in a world, which he found one-sidedly and unhealthily masculine. He read widely and deeply in his youth but was greatly disappointed when he went to study theology at the university in Utrecht: his high hopes for intellectual enrichment were quickly dashed since he found that there was nothing less universal than the university. An exception was provided by the teachings of Bolland, the leading Hegelian philosopher in the Netherlands who, although being a conservative, stimulated in his students the growth of a strong revolutionary consciousness. De Ligt was also deeply influenced by the idealistic philosophy of Kant and especially by Fichte; from the latter’s ‘Lectures on the Duty of Intellectuals’ he was especially fond of quoting what can be seen as constituting his motto: ‘Only he is free who wants to set free the world around him.’ His immersion in theological and philosophical questions was soon followed by a thorough investigation of the social question. He preferred the French and British ‘Utopian’ and Christian socialists over the more dogmatic German ones, and was particularly influenced by Keir Hardie, William Morris and John Ruskin. He took from Ruskin the notion of socially responsible production and frequently quoted Ruskin’s words to the British workers during the Franco-Prussian war: ‘You must simply die rather than make any destroying mechanism or compound.’

In 1909 de Ligt joined the Union of Christian Socialists (Bond van Christen Socialisten, BvCS) and became its leading member until his resignation almost a decade later. In 1910 he was appointed pastor of the same little Reformed Church in the small Brabant village of Nuenen, near Eindhoven, where Vincent van Gogh’s father had been pastor 25 years before, and where the painter had lived with his parents in the parsonage for 2 years. In this period van Gogh painted both the church and the parsonage, but most famously The Potato Eaters, in 1885. In van Gogh’s ardent wish for a new social morality, for the improvement of the life of the peasants and the poor as evoked in that painting, for equal rights for women, as well as in the agony and intensity with which he experienced these social questions, van Gogh strikingly resembled de Ligt. Both men developed from being somber, tormented ascetics into free spirits, except that de Ligt lived longer to enjoy this re-birth than van Gogh who died aged 37. Long rambles in the Brabant countryside, and the daily contact with his parishioners most of whom were simple, good-natured people, made de Ligt’s five years in Nuenen one of the happiest periods of his life.

Yet, he was also witnessing the destitution of the industrial proletariat in nearby Eindhoven. In his sermons he insisted on the need for a rebirth out of a spirit of love: ‘having transformed ourselves, we want to transform the world’. He recognised the existence of the class struggle but rejected the classical doctrine, which claimed to provide the only answer to overcoming it. Like Bakunin, de Ligt always insisted that a two-fold revolution was necessary: one in the external world, affecting economic, social and political relations, and a moral and spiritual one, no less vital, inside each human being. De Ligt was deeply spiritual and could not be duped by cheap Marxist sophistries which blamed capitalism for war and for all other social miseries, and which ignored the human factors, which intermingled with the economic one. He found that the failure of organised socialism to be truly revolutionary was mirrored by that of the churches: they were stagnated by dogma, and had become pillars of the established order. Amid the general mobilization for World War I in early August 1914, de Ligt, together with A. R. de Jong and Truus Kruyt (all leading members of the BvCS), drew up a manifesto entitled ‘The Guilt of the Churches’, in which the churches’ connivance with the imperialist system, which had resulted in the present war, was roundly condemned. They also started a campaign to obtain freedom of conscience for those who refused to be conscripted. In June 1915 de Ligt gave a starkly anti-militarist sermon in Eindhoven, which resulted in his exclusion (by the commander of the army) from the southern part of the country, which was deemed to be in a state of siege. His depiction of the military as a cold, ruthless machine is brutally frank:

“There are many Romans among us, for whom the state is the highest authority which is draped in godly power. What the state orders inexorably happens. This state of affairs is embodied in that infernal military system. For what kind of a system is this? The soldier stands below the corporal, the corporal below the sergeant, the sergeant below the officer, this one below the major; finally there is the general. But he is as a lever in the hands of the government, which directs him, be it to the left, be it to the right. As soon as the government moves the general, all move with him; it is one big machine. And if the general commands ‘Fire!’ all fire regardless of the nature of the target, even be it the heart of Jesus Christ. The first demand of the militaristic state is that you banish your conscience from your heart, if need be.”

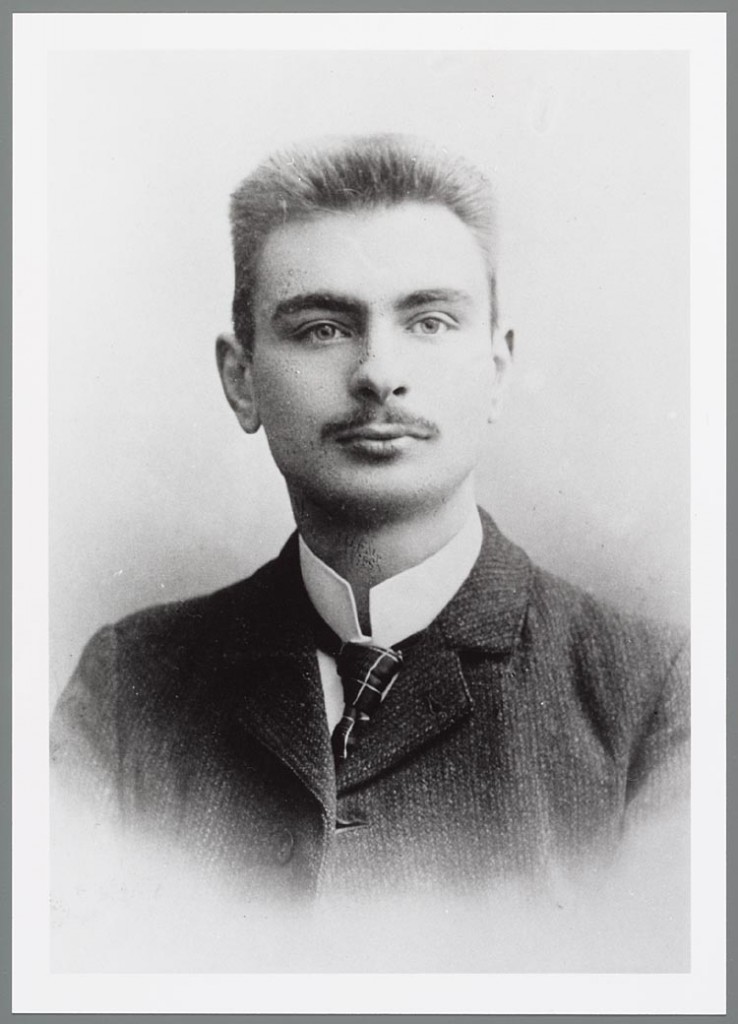

Bart de Ligt c. 1913; Public domain image; photographer unknown; courtesy of International Institute for Social History.

It can cause little surprise that the Dutch government banned de Ligt’s writings for all members of the Dutch armed forces.(2) De Ligt was imprisoned for 15 days; in the spring of 1917 he was also banned from two more provinces following another outspoken sermon. His continuous conflict with the state, and its harsh treatment of conscientious objectors, whose cause he vigorously defended together with Jos Giesen, prompted de Ligt to probe further into the nature of the state. Already familiar with Bakunin, he now versed himself in the anarchist literature, especially Proudhon and Kropotkin. What he found both clarified and sharpened his own developing insights: anarchism was grounded in a mystical-spiritual conviction, which strove for the freedom, equality and brotherhood of all. Moreover, the anarchists had kept alive the anti-militarist tradition of early socialism: they combated militarism because it constituted slavery and was an attack on the integrity of the individual personality. He began to realise that the new person and the new community he was striving for could not come about in or by the state, and he found that fundamental anarchist ideas inspired the progressive theories of educators such as Maria Montessori with whom he came into contact, ‘neither to govern, nor to be governed, but self-government, self-expression, self-development’.(3) Shortly after the end of the war, de Ligt resigned from his pastorate, and from the BvCS, since he no longer regarded himself as a Christian. As a result also of his deep study of Greek philosophy and Eastern religions, he felt he had grown beyond Christianity, quite apart from the supine attitude adopted by the churches during the war, and the lack of support for him and the few who stood out with him. De Ligt regarded all religions as mere branches of the great tree of cosmic religion and saw his decision ‘not as a question of denial, but of transcendence, not as one of impoverishment, but of enormous enrichment’. An important influence in his thinking had been the book by Jean Marie Guyau on the possibility of an independent morality not grounded in any specific religion. Guyau was regarded by several anarchists as their spiritual leader, and he rejected the idea in the Gospels of ‘love as duty’ and substituted a more generous, genuine and healthy concept of love which derived from a selfless giving, welling up from deep inside the truly human person. True morality, and the spiritual and social renewal of the individual and of society, could not be achieved through (external) coercion, de Ligt concurred, but could only result out of a deeply felt internal urge. Craftsman that he was, he was often able to express the essence of his ideas in felicitous and memorable phrases. In this case he expressed the contrast in Dutch by the words dwang and drang (coercion and pressure).

Another French philosopher (of an earlier period) whom he dearly loved was Etienne de la Boétie, whose essay ‘On Voluntary Servitude’ also impressed Emerson, Tolstoi and Gandhi. For a Dutch translation, made by one of his sisters, he wrote an introduction, and for some time this essay accompanied him as a ‘kind of new little testament’. He found in it an antidote to the modern system of state slavery and the cult of violence, which it entailed, and to the rise of fascism and the messianic expectations vested in Leninism and Stalinism; in a word, an antidote to all forms of inhuman slavery. It contained the message later proclaimed also by Godwin, Proudhon, Bakunin, Tolstoi and other anarchists, namely that the answer to human domination and exploitation lies essentially within, and not without, the individual: that in reality there are no tyrants, but only slaves. De Ligt regarded de la Boétie’s essay as a typical expression of the spirit of the Renaissance, in which the love of self-liberation was inspired by the traditions of Judea and Hellas.

De Ligt was imprisoned again in 1921 (for a month) when he organised a general strike in order to obtain the release of Herman Groenendaal, a conscientious objector who had started a hunger strike. Addressing a meeting in June 1921, de Ligt said: ‘Comrades, I have come to incite you: in the name of Jesus, in the name of Marx, in the name of Bakunin, in the name of Tolstoi, in the name of Groenendaal, I incite you to leave behind you all evil work, to refuse to build army barracks and prisons, to refuse to produce war material.’ He was arrested for incitement to foment unrest and in his defence plea wholeheartedly accepted the accusation: Yes, his aim had been to incite, to spoil youth, as another Socrates, but to spoil it for militarism and war, by awakening the consciousness of his listeners and by appealing to their sense of personal responsibility. He had just published ‘The Anti-militarists and Their Methods of Struggle’, in which he had demonstrated that war was not only evil, but also an irrational, immoral, and ineffective means of pursuing conflict. The struggle against war and for a constructive revolution had to be waged with pure means: the more exalted the goal, the purer the means for achieving it had to be, otherwise there arose the real danger of the despotism of the means, and the goal would prove to be elusive. De Ligt regarded a moral and cultural renaissance as the deepest essence of all revolution, and this goal required a re-thinking, too, of the strategy to be adopted. He was naturally a keen observer and commentator of the events in Russia, where the revolution was being bogged down in authoritarianism and where a dictatorship over anarchists and syndicalists was being exercised, and these developments only confirmed his deeply held view of the inextricable bond existing between means and ends.

During Easter of the same year, 1921, de Ligt took the initiative in creating the International Anti-Militarist Bureau (IAMB), the successor to Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis’s International Anti-Militarist Union (IAMV), established in 1904. Nieuwenhuis was the father of the Dutch labour movement, and his career offers interesting parallels with de Ligt’s: he also started out as a clergyman, who became dismayed with the institutional church and with institutional socialism, and ended up as the leading Dutch anarchist.(4) In the Second International he was an outspoken advocate of the idea of a general strike by workers should war be declared. After the expulsion of the anarchists from the International, Nieuwenhuis pursued his campaign for direct action to paralyse the war machine through the IAMV. When he died in 1919, de Ligt became his de facto successor. De Ligt, like Nieuwenhuis, always decried the repudiation by the social democratic movement and the Second International of the vigorous and uncompromising anti-militarist position adopted at the 1868 congress of the First International. In a pamphlet published in 1918, de Ligt exhorted soldiers and workers to strike and to become conscious of their power and responsibility: ‘The capitalists make war’, he wrote, ‘but the proletarians make it possible.’ Neither the IAMV, which de Ligt had joined at the end of the war, nor the IAMB, were entirely pacifist in their orientation. The IAMV was not so much against violence as against the state and the system of capitalism, which were held to carry the seeds of imperialism and war in them. The IAMV emphasised mass action and played down the significance of individual conscientious objection (whilst respecting it) as a revolutionary tool; the IAMV questioned the viability of individual economic non-cooperation given the economic dependence of the worker. However, by the time de Ligt joined the IAMV it had become more sympathetic to his position (which stressed the importance, in the revolutionary struggle, of individual responsibility and action), partly because of the increase in the number of conscientious objectors during the war. The IAMB grew out of the IAMV and de Ligt became its most able and also its most dedicated worker: under his editorship its organ, De wapens neder (Lay Down Your Weapons) became a first-rate forum for discussion. De Ligt’s writings, no less than his activities during the war (and afterwards in support of Groenendaal) contributed significantly to the passing of the first Dutch law on conscientious objection in 1923.

Although anti-militarism figured prominently in de Ligt’s thought, writings and activities, he regarded it as part of a much wider task, namely the creation of a new culture and society. This required the combating of militarism and reaction, and also a profound renewal throughout society — affecting philosophy, education, the arts, medicine, and science. De Ligt’s encyclopedic mind was well informed in all these areas and he followed keenly the latest developments in the hope of finding in them evidence of the beginnings of a world renaissance which he believed was taking place. The new society, which he envisaged and strove for, implied the liberation of workers, women, colonial peoples and intellectuals from their ignominious slavery. Nothing less than a new history, a worldwide renaissance, the unfolding of a cosmic plan, was his goal. He rejected the view of Max Nettlau that reflections on the unity of mankind were fruitless illusions. Instead, de Ligt saw this dream, this Utopia, as something which moved the world; one of his favourite expressions was ‘utopia as the world mover’: the evocation of Utopia was able to create a new awareness and stimulate a sense of individual responsibility in the consciously living personality. De Ligt aimed to create a new self-confidence for the individual, grounded in the realisation that he was an active participant in the evolution of a worldwide historic process which, while it went beyond, and greatly surpassed, each individual, yet at the same time also depended on that individual’s activities. De Ligt was far from engaging in idle speculation or wishful thinking and his attitude was always one of ‘hoping for everything, but expecting nothing’. Momentary setbacks and defeats were unable to dislodge him from his faith and works. Reginald Reynolds called him ‘the Great Utopian’, who was ‘consciously, and gladly, ahead of his time’.(5) In one way, his attitude was not unlike that of Luigi Lucatelli, who told his contemporaries: ‘Farewell, good Sirs, I am leaving for the future. I will wait for Humanity at the crossroads, three hundred years hence.’(6) Of course, de Ligt’s great dynamism and revolutionary zeal never allowed of any ‘waiting’; life for him was an incessant but uplifting and ennobling process of creation and destruction. All his life he critically examined his own ideas and attitudes and moved on beyond them. In the words of his friend, the philosopher M. A. Romers, ‘all “isms” were to him barbarisms, in which only an un-dialectical mind could become trapped.’ De Ligt was free of all dogma and his passion, like that of Tolstoi or van Gogh, knew only one kind of fanaticism: the defence of the truth. Because of his own evolution, de Ligt facilitated the growing together, especially in Holland, of religious-anarchist, libertarian-socialist and revolutionary anti-militarist tendencies. It is not surprising that de Ligt is today regarded as ‘the most creative theoretician of the European anti-militarist movement of the interwar period’ and that because of him, Holland, ‘otherwise rather in the margin of European social movements and struggles, was a center of anti-militarism in Europe in the interwar years’.(7)

In 1918 de Ligt married Catherina van Peski-van Rossem who, over the next twenty years, became his great support and who herself took an active part in the anti-war campaign. Together with her husband she wrote a book entitled New Schools in Hamburg and Vienna (1930), after they had witnessed the educational reforms taking place there, and in 1937 her essay on ‘The Best Strategy for International Disarmament’ received the first prize in a competition organised by the New History Society of New York. (She used the prize money to fund the Peace Academy, which her husband had established just before his death, and which she continued until the outbreak of war.) In 1925, in what was regarded as a temporary move, the family went to Switzerland, where they settled, permanently, near Geneva, although de Ligt returned to Holland every year for several months for lectures and meetings.

Geneva at this time was just beginning to emerge as a centre of internationalist activity because of the League of Nations. But the peace de Ligt concentrated on was of a different kind: he never expected peace to issue from a league which he regarded as consisting of capitalist-imperialist states. One of his neighbours turned out to be Pavel Biryukov, the close friend and biographer of Tolstoi. Biryukov had taken up the cause of the persecuted Dukhobors, the Russian pacifist religious sect, and was for a time banished from his country as a result. De Ligt learned from this like-minded spirit (who became a close friend) many interesting details concerning the persecution of principled anti-militarists in both Tsarist and Bolshevist Russia.

De Ligt devoted several pages to this subject in his encyclopedic history of direct action against war, published in two volumes in 1931 and 1933, Vrede als Daad (Peace as Deed). For this work, which was subtitled ‘Principles, History and Methods of Direct Action against War’, de Ligt gathered materials over several years and it became his life work. De Ligt was in the process of preparing a French translation of it when he died; in this expanded version, four volumes were planned, of which two were published in 1934 under the title La Paix Créatrice. His death prevented not only the completion of the French edition but also the likely appearance of an English translation. Even so, we can be grateful that La Paix Créatrice inspired Peter Brock to write his unique, three-volume History of Pacifism; for him, de Ligt’s work represented ‘a truly pioneering venture.’(8) De Ligt demonstrated in his history the thesis that the anti-militarist movement is essentially concerned with creating a new culture. The book also provided the movement with a history and tradition. He wrote, ‘We never forget that the new future which we envisage also requires a new tradition which we have to create. Man is an historic being: nothing lends more power to a movement than the realisation on the part of its carriers that their movement emerges out of a long and inextinguishable past.’ For this book he reread history from a new perspective and in this way transformed our view and understanding of the past. He aimed to demonstrate how humanity advanced from a largely unconscious and instinctive mode of living to one in which it consciously created its own circumstances and shaped its own destiny. He amassed an overwhelming amount of facts, which showed that the non-violent resistance to violence, war and cruelty is a universal phenomenon, which can be found in all cultures and in all eras. By building on this (often forgotten and repressed) past, new generations would increasingly transform human society into a humane one.

Apart from his magnum opus, de Ligt’s prolific writings included a dozen books (several of which were translated into French, German and English), nearly a hundred pamphlets and hundreds of journal articles.(9) During the last ten years of his life he was also editor of the leading Dutch peace journal, Bevrijding (Liberation). The debates conducted in its pages were of a very high standard and have lost little of their relevance. During his years in Geneva de Ligt was centrally involved in the organisation of the radical peace movement and he became a leading member, for instance, of the War Resisters International (WRI). At its conference in Welwyn (Herts) in July 1934 de Ligt presented his famous ‘Plan of Campaign against All War and All Preparation for War’ (reprinted in full in The Conquest of Violence).(10) Contrasting the continuous and systematic mobilisation for war with the complete lack of practical plans for its prevention and resistance, de Ligt submitted an earlier version of his plan to a conference of the ‘Student Peace Action’ (Studenten Vredes Actie) in February 1933, and this was published in the same year under the title ‘War against War: What Every One Can Do in This Respect’ (in Dutch only). In 1934 a fuller version was published under the title Mobilisation against War! A Plan of Campaign, in four languages. Modern theoreticians and practitioners of direct non-violent action have been struck by its originality and continued relevance. Gemot Jochheim writes that ‘still today, de Ligt’s Plan is the most systematic plan of a non-violent struggle against militarism [available]‘ and Michael Randle calls it ‘the classic text’ of the literature dealing with direct action against war and war preparation. He writes, ‘Even today, almost half a century after its publication, it is striking for its imaginative radicalism.’(11)

Even before Julien Benda’s book La Trahison des Clercs was published in 1927, de Ligt pursued the theme of the special responsibility of scientists and intellectuals for war. As early as 1921-22 he tried to create an international organisation of socially responsible scientists who refused to engage in war work of any kind. De Ligt regarded as a milestone the Anti-Gas Warfare Conference, which was convened in Frankfurt in January 1929 by the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). In his speech, ‘Intellectuals and Modern War’, he argued that all who fashioned the war machine, proletarians and intellectuals alike, were responsible for war, but he blamed especially the latter because of their failure to raise the moral standards of the former. He accused the vast majority of priests and teachers, historians and journalists, political and social leaders, chemists and engineers, of having fallen lower than the women who sell their bodies. ‘Already Rabelais knew’, he said, ‘that science without conscience is the ruin of humanity.’ It was an urgent task to awaken in scientists and intellectuals a new consciousness of their individual responsibility for the barbaric war, which was being prepared everywhere. In the following years he engaged in a vast correspondence with many of the leading minds of the time, including such figures as Einstein, Gandhi and Huxley, in order to bring about an international organisation to promote this goal. De Ligt envisaged a type of organization, which emerged in the 1980s in the UK and the USA, namely ‘Professions for Peace’. However, pressure of work prevented him from realising this project although he revived it in a somewhat different form with the creation of the Peace Academy, whose aim was to lay the foundations for a ‘Science of Peace’.(12) This was also the title of the inaugural lecture prepared by de Ligt for the first summer school of the Peace Academy, held in Jouy-en-Josas near Paris in August 1938, which was read in his absence since he was too ill to attend. ‘The responsibility of the intellectuals’ constituted the theme of the first half of the lecture, which is reminiscent of the one given almost ten years earlier at Frankfurt. He regarded the Peace Academy ‘as a first attempt to unite the different tendencies which appear in the world of today towards a rebirth of science, an essential condition for a rebirth of humanity.’ De Ligt’s proposal for a ‘Science of Peace’ is as original and as relevant now as his ‘Plan of Campaign’; as Jochheim notes, ‘it could have been written today.’(13)

De Ligt was not only a great scholar of pacifism. H. Runham Brown, the long-serving secretary of the WRI, referred to him as ‘the philosopher of our movement’, and a great agitator of mind and spirit. He was also an exceptional organiser. This was recognised by all those who were personally acquainted with him through many of the organisations in which he was actively involved (which, in several cases, he had also initiated). ‘It was one of de Ligt’s missions in life’, Brown has written, ‘to harmonise and to bring closer together the various factions in the anti-militarist movement.’(14) In organisations and at conferences he was recognised as a unique peace-maker, without, however, being an opportunist or pragmatist: he was inflexible in his convictions and, while being very tolerant, never a man of compromise. At the WRI conference in July 1937 in Copenhagen, de Ligt was a lone figure in condemning the personal peace crusade of the organisation’s chairman, George Lansbury, who had been to see Hitler and Mussolini in an attempt to bring about, in de Ligt’s view, ‘a compromise amongst the various imperialisms’. De Ligt insisted that the WRI should distance itself from its chairman’s private activities since ‘we fight for the abolition of the causes of war; but we do not fight for a capitalist peace.’ Reynolds, who met de Ligt frequently in WRI meetings, commented: ‘In the most calm, good-natured, friendly and patient manner imaginable, he remained a refractory extremist, a rock of resoluteness upon whom one could always build.’

Within days of the Copenhagen meeting of the WRI, de Ligt attended the first meeting of the ‘International Assembly Against War and Militarism’ (Rassemblement International Contre la Guerre et le Militarisme, RIGM) in Paris. This was yet another attempt to bring together all anti-war organisations of absolute pacifists with the aim of constructing a minimum programme, at a far from propitious time. The assembly was called by the French ‘International League of Fighters for Peace’ (Ligue Internationale des Combattants de la Paix, LICP) but the inspiration for it had come from de Ligt, who had been preparing this meeting since 1935 with the encouragement of Félicien Challaye, the LICP’s president. The latter highly praised de Ligt’s organisational talents, as did many other delegates. One of his achievements had been to persuade Gandhi to join the RIGM. Some years earlier de Ligt had been engaged in a well-publicised correspondence with ‘the great Oriental leader’, whom de Ligt admired and at the same time forthrightly criticised. He deplored Gandhi’s lack of consistency and his willingness to compromise his pacifist principles by serving with the Red Cross during the Boer War and again in 1914, when he hoped that his loyalty (and that of his country) to the British Empire would be rewarded by the granting of dominion status to India. When de Ligt met Gandhi in Lausanne and Geneva in 1931, the latter had just attended the Round Table Conference in London where he had demanded for India control over her own defence forces, yet he advised the Swiss people and the Western nations to renounce violent national defence and to free themselves from all armaments by practising direct non-violent action. De Ligt spelt out the contradictions of this position, and expressed the hope that Gandhi would come round ‘to the point of view of the revolutionary anti-militarists’. He wrote, ‘One might apply to the Mahatma the biblical words: “Physician, heal thyself”.’(15) De Ligt had criticised Romain Rolland (with whom Gandhi was staying while in Switzerland) for being silent in his writings on the ‘irresponsible…war propaganda made by his revered Indian in 1918′, adding: ‘We are no longer in need of an infallible messiah!’ De Ligt had written his open letter to Gandhi precisely to counter the tendency towards creating a new messianic cult, and to prompt Gandhi and his disciples to break decisively with nationalistic and militaristic opportunism.(16) De Ligt’s evaluation of the Indian leader is also to be found in the volume reprinted here.

The Conquest of Violence was an expanded version of a book published in French in 1935, which itself was an enlarged translation of the 1934 Dutch edition (for de Ligt, a translation always implied the need to rework, sometimes substantially). The appearance of an English translation was doubtlessly helped by de Ligt’s acquaintance with Aldous Huxley who, in the mid-1930s, had become a prominent figure in the peace movement and who was keenly interested in the possibility of non-violent resistance to war and aggression. They met for the first time at the Universal Peace Congress held in Brussels in September 1936, which Huxley attended as a member of the Peace Pledge Union (PPU) delegation. A few months after this meeting, Huxley visited de Ligt in Geneva and for several days they engaged in intensive discussions on the need to rethink the scientific, moral and cultural bases of modern socialism and, inextricably bound up with this, on the struggle against war. By the end of the following year (1937), both Huxley’s Ends and Means and de Ligt’s book appeared. Huxley had recommended to Routledge an English edition of the French book by de Ligt which he had read and which he found quite unlike most other pacifist books since it dealt fully with the problems of social change, revolution, and war problems which were acute.

The reputation, which The Conquest of Violence acquired following its publication, is remarkable in view of the fact that it was not long before the start of the Second World War. Yet, in this period it was widely studied by peace groups (in England especially by the Peace Pledge Union) and it immediately established itself, next to Richard Gregg’s The Power of Non-Violence, as ‘the textbook of non-violent revolution’ (Fenner Brockway). George Woodcock refers, less felicitously, to ‘that extraordinary manual of passive resistance’ (17) for this technique comprises only one aspect of de Ligt’s revolutionary pacifism and the word ‘passive’ in conjunction with peace or pacifism normally conjures up unfortunate connotations which, if sometimes true, are wholly false in the case of de Ligt. Charles Chatfield refers to de Ligt’s ‘classic and monumental book…which, with R. Gregg’s, constituted the most influential exposition of war resistance in the interwar period’. His work, he writes, ‘must be accounted the great departure for systematic analysis and plans of civilian nonviolent resistance’, and the ‘Plan of Campaign’ plays a decisive role in Chatfield’s evaluation of de Ligt’s ideas.(18) The continued interest in, and admiration for, The Conquest of Violence can be explained by the fact that the task expressed in the book’s title is an imperative of our age and by the growing recognition that continued reliance on nuclear deterrence (in particular) to prevent war is both morally and rationally highly questionable. The quest for non-violent methods of waging conflict is even more urgent today than when de Ligt wrote, and the depth of his exposition is a guarantee that his voice will continue to be heard.

Endnotes

(1) A full biography of Bart de Ligt is still to be written. The nearest we have is the commemorative volume Bart de Ligt 1883-1938 (Arnhem: Van Loghum Slaterus, 1939). In this Introduction I have frequently drawn on the various contributions in this excellent volume, especially on the long biographical sketch by H. J. Mispelblom Beijer which takes up almost half of the book. Bart de Ligt’s Kerk, Cultuur en Samenleving: Tien Jaren Strijd (Church, Culture and Society: Ten Years of Struggle), Arnhem: Van Loghum Slaterus, 1925, a collection of important writings, is preceded by a lengthy autobiographical account. There is a moving biography by his wife in an anthology of de Ligt’s writings published in 1951: H. Kuijsten et al. (eds), Naar een Vrije Orde (Towards a Free Order), (Arnhem: Van Loghum Slaterus).

(2) This fact is mentioned by Dr Arthur Lehning in an article commemorating the centenary of the birth of de Ligt: ‘Vrede als Daad: Arthur Lehning over de Actualiteit van Bart de Ligt’ (‘Peace as Deed: A. L. on the Topicality of B. de L.’) in NRC Handelsblad, 10 Dec 1983. Lehning, the editor of the ‘Bakunin Archives’, was a close friend of de Ligt, about whom he has written several incisive pieces, including his introduction to the 1939 commemorative volume. I have been unable to establish whether this government order was issued during the First World War or afterwards.

(3) See also Appendix I in The Conquest of Violence.

(4) Harold Josephson (ed.), Biographical Dictionary of Modern Peace Leaders (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1985) contains biographical sketches of Nieuwenhuis and of other leading Dutch radical anti-militarists with whom de Ligt was in touch: Kees Boeke, G. J. Heering, J. B. T. Hugenholtz, Albert de Jong, Clara Meijer-Wichmann and Henriette Roland Hoist-Van der Schalk.

(5) Reginald Reynolds, ‘Bart de Ligt as I Knew Him’ (in Dutch) in the 1939 commemorative volume, pp. 194-8.

(6) Quoted in Hendrik Willem Van Loon, The Liberation of Mankind: The Story of Man’s Struggle for the Right to Think, (London: George G. Harrap, 1941.)

(7) Gernot Jochheim, ‘Bart de Ligt: Gewaltlosigkeit und anti-militaristische Aktion’, in Christiane Rajewsky and Dieter Riesenberger (eds), Wider den Krieg: Grosse Pazifisten von Immanuel Kant bis Heinrich Böll (Munich: C. H. Beck, 1987, pp. 103 and 106). De Ligt features prominently in Jochheim’s important study of the development of the idea of non-violence in the European, particularly Dutch, anti-militarist and socialist movements in the period 1890-1940: Antimilitaristische Aktions-theorie, Soziale Revolution und Soziale Verteidigung (Assen/Amsterdam: Van Gorcum and Frankfurt am Main: Haag + Herchen, 1977).

(8) Peter Brock, Pacifism in Europe to 1914, (Princeton University Press, 1972; p. 505.)

(9) A virtually complete bibliography of de Ligt is to be found in the 1939 volume, pp. 256-72.

(10) Headley Brothers, the printers of the book, asked Routledge, the publishers, to scrutinise de Ligt’s Plan in view of the Incitement to Disaffection Act which had recently become law. The publishers took counsel’s opinion on the matter. For this, and other details surrounding the publication of the book, see my article, ‘Bart de Ligt, Aldous Huxley and “The Conquest of Violence”: Notes on the Publication of a Peace Classic’, in Herman Noordegraaf, Peter van den Dungen and Wim Robben, Bart de Ligt: Peace Activist and Peace Researcher (Boxtel, Netherlands: Bart de Ligt-Fonds, 1988).

(11) Jochheim in Wider den Krieg, p. 109; Michael Randle, ‘Pacifism, War Resistance, and the Struggle Against Nuclear Weapons’, in Gail Chester and Andrew Rigby (eds), Articles of Peace: Celebrating Fifty Years of ‘Peace News’ (Bridport, Dorset: Prism Press, 1986) p. 28. There are also references to de Ligt in the contribution by Geoffrey Ostergaard to the same volume, ‘Liberation and Development: Gandhian and Pacifist Perspectives’ (pp. 142-68). It is unfortunate that de Ligt’s name is not to be found in Devi Prasad (ed.), 50 Years of War Resistance: What Now? (London: War Resisters’ International, 1972).

(12) See the short article, ‘The Peace Academy’, by its international secretary, Catherina de Ligt-van Rossem, in Interpax (London: Newssheet of the International Pacifist Association, no. 4, May 1939, pp. 1-3).

(13) Jochheim in Wider den Krieg, p. 103. Thanks to R. H. Ward there is an English translation of de Ligt’s important lecture: Introduction to the Science of Peace (London: Peace Pledge Union for the Peace Academy, 1939) pp. 32. Ward also reviewed The Conquest of Violence in Peace News (no. 75, 20 November 1937, p. 8).

(14) H. Runham Brown, ‘Barthelemy de Ligt”, obituary in The War Resister (no. 45, Summer 1939, p.30).

(15) Bartholomew de Ligt, ‘Mahatma Gandhi’s Attitude Toward War’, in The World Tomorrow, 1932, and reprinted in Charles Chatfield (ed.), The Americanization of Gandhi: Images of the Mahatma (New York: Garland, 1976) pp. 712-19).

(16) Bart de Ligt, ‘Tolstoi en Gandhi’, in Naar een Vrije Orde, pp. 144-5. In 1924 he had written that Gandhi was undoubtedly a revolutionary in respect of the means of struggle, which he advocated but appeared somewhat of a reactionary in respect of his goals. Kerk, Cultuur en Samenleving, p. XXXV.

(17) George Woodcock, Anarchism (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1963) p. 413. He adds that The Conquest of Violence led many British and American pacifists in the 1930s to adopt an anarchist point of view.

(18) Charles Chatfield (ed.), International War Resistance through World War II (New York: Garland, 1975) pp. 33, 44 (note 39) and 558.

A NOTE ON THE TEXT: This biographical essay serves as the Introduction to Bart de Ligt, The Conquest of Violence, London: Pluto Press, 1989; pp. ix-xxvii.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Peter van den Dungen is Honorary Lecturer at University of Bradford, Department of Peace Studies and general coordinator of the International Network of Museums for Peace. He was a former fellow of the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, and is the author of: West European Pacifism and Strategy for Peace, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1985; and, From Erasmus to Tolstoy. The Peace Literature of Four Centuries; Jacob ter Meulen’s Bibliographies of the Peace Movement before 1899, Wesport (Ct.): Greenwood Press, 1990.