Author Archive: William J. Jackson

WILLIAM J. JACKSON is our Literary Editor and a regular contributor. He was born and grew up in Rock Island, Illinois, and studied at Goodman Theatre School at the Art Institute of Chicago, at Lyndon State College in Vermont's “Northeast Kingdom,” and at Harvard University where he earned his PhD in the Comparative Study of Religion in 1984. He is professor emeritus of religious studies at Indiana University-Purdue University. He was the first Lake Scholar (2005-2008) at the Lake Family Institute on Faith and Giving, Philanthropic Studies Center, Indiana-Purdue University. His academic specialties are the comparative study of religion, Asian arts and literature, South Indian bhakti (devotion) in the lives and works of singer-saints. He is also an authority on Fractal Geometry in the Humanities, that is, recursive patterns in music, literature, art, and architecture. His awards include a Research Fellow, Bellagio, Italy Research Center Rockefeller Foundation, 2000; and Contemplative Practice Fellowship Program, American Council of Learned Societies, 2000.

Most recently Dr. Jackson has published a novel,

Gypsy Escapades, New Delhi: Rupa & Co, 2012, on the themes of terrorism and satyagraha. Another novel also came out recently,

The Singer by the River, an ebook available from

Sruti magazine, Chennai. It is an historical novel about South India's greatest composer, Tyagaraja. Further information about Dr. Jackson is available on

Indiana University’s website and

at academia.edu.

by William J. Jackson

1. The Activist Author

Around a decade ago I would see American news programs showing ambulances at a scene of broken glass and chaos, caused by a Palestinian suicide bomber targeting Israeli civilians. Those scenes made me wonder what life must be like for ordinary Palestinians and sympathetic pacifists among the Israelis.

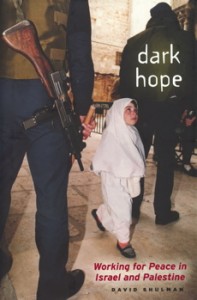

Cover image courtesy Reuters/Corbis & University of Chicago Press

Dark Hope (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007) is a poignant book about Israeli activists’ outreach efforts to befriend and support Palestinians whose homes and fields had been impinged upon by settlers and security measures. The author belongs to a voluntary group named Ta’ayush, Arab-Jewish Partnership, formed in 2000. This alliance is “dedicated to the pursuit of peace, to ending the occupation, and to civic equality within Israel proper.” (p.1) Israeli members of Ta’ayush go out of their comfort zones to publicly take a stand to support endangered Palestinian villagers.

Of course, Ta’ayush is not alone in this work. There are similar Israeli groups, such as Rabbis for Human Rights, The Israel Committee Against House Demolitions, Bar Shalom, Gush Shalom, Kids4Peace, etc. Shulman writes of Ta’ayush: “We follow the classical tradition of civil disobedience in the footsteps of Gandhi, Thoreau, Martin Luther King.” He says the goal is “to construct a true Arab-Jewish partnership” and he quotes Ta’ayush literature: “A future of equality, justice, and peace begins today, between us, through concrete, daily actions of solidarity to end the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories and to achieve full civil equality for all Israeli citizens.” (p. 11)

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

When I taught university courses in which students read and discussed Gandhi’s Autobiography, I always found it rewarding to consider the early formative influences in his life, which Gandhi discussed in the opening chapters. These influential experiences are interesting to consider, because as Wordsworth wrote, “The child is father to the man.”

Mohandas Gandhi’s father had “rich experience of practical affairs” though he was uneducated in fields like history and geography. (Mohandas K. Gandhi, Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth, New York: Dover Publications, 1983, p. 2) His mother made an impression of saintliness, with practices of daily prayer and fasting. One practice was vowing not to eat during the day until seeing the sun. Gandhi and his brother would run out on cloudy days and look at the sky when it seemed the sun was coming out, then run back in and tell her they saw the sun. And she would go out and look, and not seeing the sun, would continue fasting, cheerfully saying, “God did not want me to eat today.” She was a daily lesson in loyalty to a vow, self-control, and self-deprivation. (pp. 2-3)

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

Reading Gandhi’s Autobiography I get the impression that he was a very scrupulous person. Few public figures today seem to have such a self-scrutinizing philosophy as he did. People strategize, calculate, do what’s convenient and politically expedient; they often don’t seem to care very much about the fairness of tactics, the feelings of the opponent, or to consider a need for self-purification. (Perhaps that’s why noble-sounding politicians and other leaders so often crash and burn in episodes of disgrace and scandal.)

In Gandhi’s viewpoint criticizing others, without examining one’s own conscience, is hypocritical, and makes one unworthy of winning a noble goal. Fortunately, Gandhi had a playful personality and a great sense of humor, so even while making serious demands on himself; he did not become unbearably self-righteous—which can be an occupational hazard for men with an acute sense of scruples. He was not just a picky eater and a tiresome stickler for details, but a soulful explorer, a restless seeker for answers and methods who kept things in perspective by poking fun at himself.

Gandhi believed that to have access to truth, (satya, a concept with ancient roots in India, associated with that which endures) possessions and passions are often obstacles. In Indian culture the background and ethos of yoga, with practices of self-control, for many centuries has been influential. Even an ancient Sanskrit classic on statecraft and military tactics will advise kings to practice self-control: “Whatever sovereign is of perverted disposition and ungoverned senses, must quickly perish. The whole of this science has to do with a victory over the powers of perception and action.” (Kautilya, Arthasastra)

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

When we see that change is needed in some sphere of life, how might we disrupt business-as-usual in a civil way? Gandhi asked that question and proceeded to piece together answers. His writings show the moments of his searching attempts and the discoveries and practices he found to be effective. Had he not made his search and written about his experiments and struggles he would not have become an exemplar giving hope to others.

Gandhi had a great awareness of language. As he worked over the years to address social issues he developed a memorable vocabulary for key principles he discovered. Gandhi’s vocabulary of non-violence was useful in forming signposts for co-workers; mottos to keep philosophical ideas in focus while activists faced conflicts, such as being beaten with sticks during a protest. Gandhi needed to develop a program with strategies and teachings for protesters, showing them how to deal with natural feelings of anger, fear, and anxiety, and how to tap into “inborn gentleness and desire to do the opponent good,” as he wrote in his Autobiography. Without practice in these disciplines, the masses involved in public demonstrations would naturally become unruly and resort to violence.

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

Gandhi on the Salt March, 1930; public domain photo; photographer unknown

The image of Gandhi in action, walking with a staff in his hand, is well known. We see it in newsreels, statues, films and photos. Thomas Merton described Gandhi as a human question mark. Perhaps we should amend that to “a walking human question mark” moving across the landscape. He was a man on the move, inquiring why injustices exist and how to remedy them.

When Gandhi returned to India after being away for years studying in England and practicing law in South Africa, he tirelessly traveled all over the subcontinent. He went to places where he was invited to resolve conflicts, and was constantly taking the pulse of the people of India, assessing their needs and views, diagnosing the nation’s ills, and, when possible, trying to address them with his legal expertise. During much of this period he traveled by trains in third class cars.

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

Thornton Wilder published Heaven’s My Destination in 1935, seven years after winning the Pulitzer Prize for The Bridge of San Luis Rey. The main character, George Brush, is a Depression-era twenty-three year old. He is a socially awkward naïf; he seems a simpleton to most people he meets. A traveling salesman, evangelist, and pacifist, he is at odds with general American sentiment regarding such things as money and worldly success, and he gets in trouble for proclaiming religious statements in public, often writing them on hotel desk blotters.

Front dust wrapper current edition; Harper Collins; cover photograph copyright © Getty Images

The mishaps of this misfit, his miss-steps, mistakes and misunderstandings repeatedly cause him discomfort. He is a kind of American Candide, a Don Quixote, or a Kafkaesque bumbler who never quite sees why his extreme idealism puts off so many people. Yet Brush is quite successful at selling schoolbooks, and he has a great singing voice, so he appears attractive to some people some of the time. But as soon as he begins talking about his theories and beliefs he loses people’s sympathy.

Thornton Wilder once wrote that “Art is confession; art is the secret told.” What is the “secret” expressed in the story of Heaven’s My Destination? I would suggest it is that humanity is disappointingly cynical, and our faiths only roughly approximate higher principals; they are not perfect guides, which we can force others to accept as their own. The implications of this open secret for learning as we go through life, for finding a viable path, are profound. I think this book written nearly eight decades ago tells a fable still valuable in our time, which has its own extremists. By depicting the curious antics of an extremist, it shows us what it takes to make a “true believer” begin to take idealistic teachings with a grain of practical salt. It shows that it is not wise to be too vehement in inflicting our doctrines on others, and that literalism is dangerous, causing nice people to act like fanatics.

Read the rest of this article »

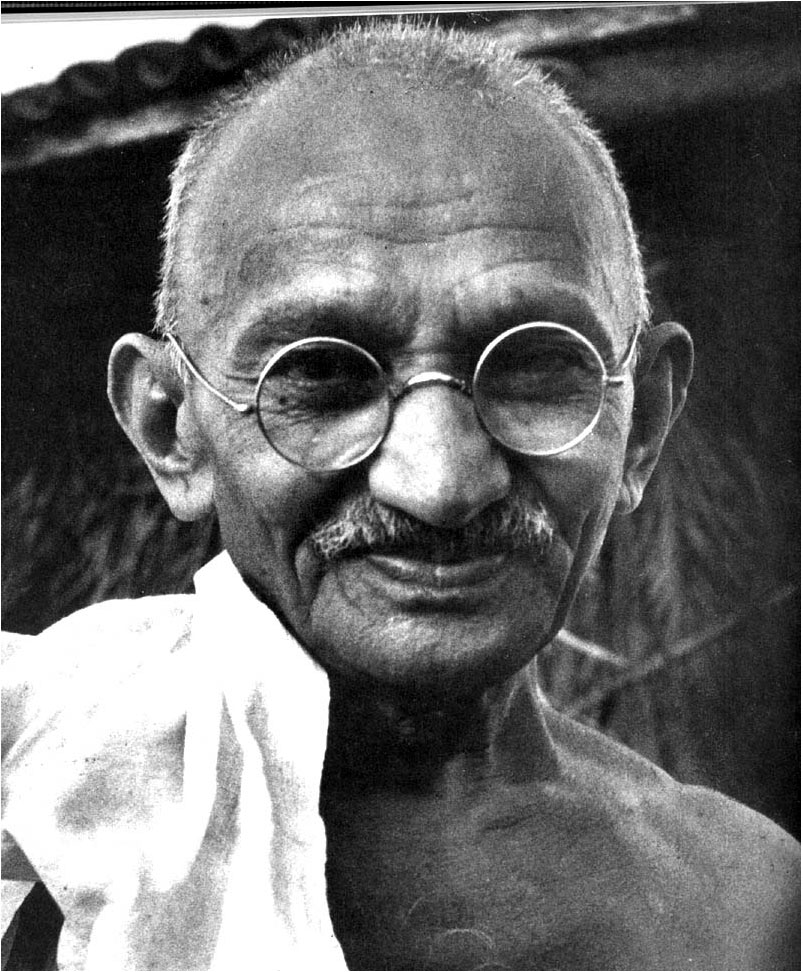

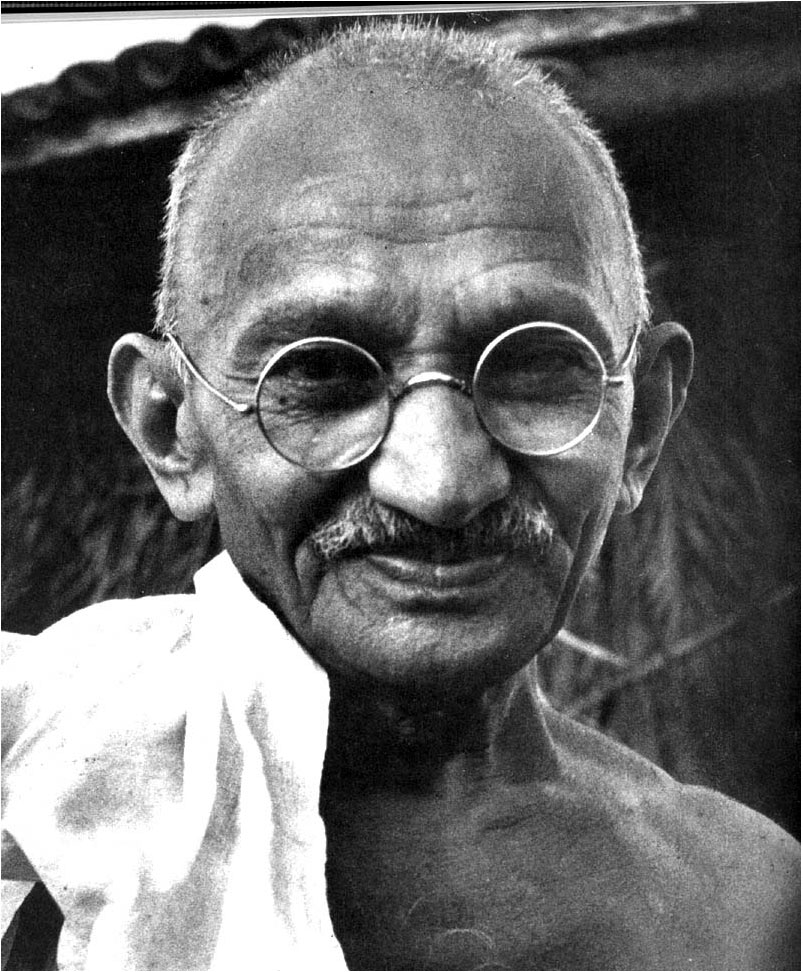

Gandhi c. 1945; photographer unknown;

a public domain image,

courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Changing the world begins with changing yourself; you have to become the change you want to see in the world.” M. Gandhi

The most Gandhi-like person I know is a very patient and gentle yogi who lives in New Delhi. When I wrote to him to say that I was preparing this article, he replied, “Making an honest and sincere attempt to practice exactly what one preaches is not easy—but Gandhiji did it to near perfection; at the cost of enormous physical as well as mental hardship, he examined his life in light of his convictions with brutal honesty, and underwent enormous inner suffering whenever he found himself wanting. That can give much greater torture than giving up physical comforts voluntarily, in which he also went to an extreme.”

Why was Gandhi so scrupulous? He himself said: “You have to become the change you want to see in the world.” Gandhi said that he thought Leo Tolstoy was the embodiment of truth in the age in which they lived: “Tolstoy’s greatest contribution to life lies, in my opinion, in his even attempting to reduce to practice his professions without counting the cost.” Gandhi said that reading Tolstoy’s writing “The Kingdom of God is Within You” changed his life, turning him from a votary of violence to an exponent of non-violence. Like Martin Luther King Jr., whom he inspired in turn, Gandhi always seemed ready to put comfort aside and to put his life on the line, without counting the cost. For example, when a leper came to his door in South Africa, Gandhi fed him, offered him shelter, dressed his wounds, and looked after him.

Read the rest of this article »