Arne Naess and Gandhi

by Thomas Weber

Arne Naess c. 2005; courtesy deepecology.org

The important philosopher of deep ecology and Gandhian philosophy, Arne Naess, died in January 2009. (1) Not one Australian newspaper or media outlet referred to this event. The news did not even make it into the obituary columns of such global weeklies as Time magazine (although, as usual, many sporting and film personalities did). Naess’s life was a significant one, and his philosophy still is. While environmentalists may know something about Naess’s thought, they tend to know little of its Gandhian antecedents. Those interested in Gandhian philosophy generally tend not to know of Naess’s contribution, but should. In short, Arne Naess should be remembered and his work examined.

A Personal Background

During 1996, as a Gandhi researcher and teacher of peace studies, I spent a few weeks as a visiting fellow at the Oslo Peace Research Institute. While in the city, I had decided to look up Arne Naess. I knew that in Norway he was an icon and that probably he had more environmentalists beating a path to his door than he needed. I, however, wanted to visit him because he had written one of the best (but least known) analyses of Gandhian nonviolence available in English – Gandhi and Group Conflict: An Exploration of Satyagraha. (2)

As a Gandhi scholar, I knew the Gandhi literature reasonably well and was often amazed to see learned articles on Gandhian philosophy that overlooked his book completely. Of course, this is the result of coming from a small out of the way country and having your landmark tome published by the Norwegian University Press. When I called on him, he was polite but seemed a little world-weary until I told him that I wanted to talk about the Mahatma because of his major contribution to Gandhi scholarship.

Suddenly he seemed interested, confirming the numbers who came through his door wanting to discuss deep ecology. So we conversed about Gandhi, and when he came to Australia for a conference in the following year my family had the honour of him staying at our house in the countryside for a short while. At that stage I knew very little about deep ecology and he was happy to be immersed in my Gandhi library. He very kindly signed Gandhi and Group Conflict, and the earlier book on which a large portion of it was based, Gandhi and the Nuclear Age. (3) He also found another of his early books on my shelves, one that I had to admit that I had only glanced at but still had noticed that Gandhi was not mentioned anywhere in the text. He explained that the book, Communication and Argument: Elements of Applied Semantics, (4) was about a Gandhian way of arguing but he deliberately left Gandhi out in order that the book be taken seriously. Gandhi, in at least to a small part thanks to Arne, has come a long way since then.

I had a feeling that the ever playful Arne sometimes found adults, and possibly this may have included me, somewhat boring and preferred the company and spontaneity of children. He spent many hours on the floor playing with our ten-year-old. And when it dawned on our child that she had a real live captive philosopher at her disposal, she produced a questionnaire, as was the then trend among her primary school peers, for him to fill out. Because we had occasionally “played philosophers”, she listed questions such as: “What is the meaning of life?” and “How do we know that when we think we are awake we are not actually dreaming?” Arne of course laughed and asked for a less difficult task, so our child produced a written list of the standard questions that were floating around her classroom: What is your favourite food? What is your favourite colour? What is your favourite country? What is your favourite animal? What is your favourite sport? What are your favourite clothes? What is your favourite movie? What is your favourite number? Do you have any pets? What is the place you would most like to visit? And, what is your favourite book? Arne, who always took children seriously, looked at the questions and announced that he had to think about them carefully and that he would write the answers when he got home and had time to consider them. And of course he was as good as his word. A few weeks later the list arrived back with the answers filled in, neatly written in green ink, in his own hand. And those answers were telling. His favourite food was simple fare: oatmeal, cornflakes, meat and potatoes; his favourite country, needless to say, was Norway and the place he most wanted to visit was his mountain cabin Tvergastein (not Disneyland!); his favourite colour: green (what else?); favourite animals: moose and pig; favourite sport: skiing and climbing when young; favourite clothes: “old ones”; his favourite number, which must have been intriguing to a ten-year-old, was 2 to the 10th power; although he had no favourite song or pets at present (however he liked his sister’s dog), he did have favourite books and movies. It is no surprise that his favourite book was Spinoza’s Ethics, and his favourite film was Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (as well as “all Chaplin films”). (5) Little else could have been expected from someone who was living the Gandhian ideal of “simple living and high thinking” and who looked for the meaning of life in the underlying unity of not just the self and other, but the self and all life.

Arne Naess’s father died when he was only one year old and he never really formed a close bond with his mother and consequently “feeling apart in many human relations, I identified with nature.” (6) While he grew up in Oslo, he often holidayed at the family’s mountain cottage:

“From about the age of eight a particular mountain became for me a symbol of a benevolent, fair-minded, strong ‘father’, or of an ideal human nature. These characteristics were there in spite of the obvious fact that the mountain, with its slippery stones, icy fog and dangerous precipices, did not protect me or care for me in any real way. It required me to show respect and take care. The mountain loved me but in a way similar to that of my 10 and 11 year older brothers who were eager to toughen me up.” (7)

He tells the story of walking in the highest mountains of Norway at age fifteen. He was stopped by a snowdrift, and had nowhere to sleep. Finally he came across a very old man and stayed with him for a week in a mountaineering cottage. They talked about nature and the old man played the violin. “The effect of this week established my conviction of an inner relation between mountains and mountain people, a certain greatness, cleanness, a concentration upon what is essential, a self-sufficiency; and consequently a disregard of luxury, of complicated means of all kinds.”(8)

When he was twenty-six, he built a hut for himself on his favourite mountain. This, the highest private dwelling in the country, he called Tvergastein, after the name used for the quartz crystals found in the area. Throughout his life he spent as much time as he could, living as simply as possible, in the splendid isolation of his hut.

The rugged Norwegian countryside, with its small population and rural culture, was an early formative factor, (9) and of course Arne was the product of a long Norwegian nature tradition with its own particular cognitive-ethical fabric. (10) As a philosopher he researched and was influenced by Spinoza (11) who maintained a spiritual vision of the unity and sacredness of nature and believed that the highest level of knowledge was an intuitive and mystical kind of knowing where subject/object distinctions disappeared as the mind united with the whole of nature. (12) Of course, for those who know where to look, as important as those inputs were, they are not the only ones.

I’m not sure if Arne was much of a moviegoer, but the fact that he singled out Attenborough’s Gandhi film is a key piece to understanding his intellectual trajectory. The earlier influences may have predisposed a young Arne to a relatively ascetic and very inclusive worldview that was not much different from the ideal of Gandhi’s philosophy. After he had earnestly taken to that philosophy, it, in turn, freed him to think in a way that would make deep ecology a logical extension of his intellectual journey.

The Influence of Gandhi

Arne Naess was born in 1912 and at the age of twenty-seven was appointed to the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Oslo as the country’s youngest professor, a job he held until 1969 when he retired to devote himself full-time to remedying the environmental problems he perceived. In between, he was part of the Norwegian resistance movement against Nazi occupation and took part in the first ascent of Tirich Mir, the highest peak (at 7,690 metres) in the Hindu Kush, as part of the Norwegian team in July 1950. Of course he is best known for coining the term “deep ecology” in 1973 (13) and being the champion of an ecological movement that operates out of a deep-seated respect and even veneration for all ways and forms of life. If one knows the Gandhi literature well enough, or indeed reads Naess’s works on Gandhi, the profound influence of the Mahatma on Naess and his philosophical work, including on ecological philosophy (or “ecosophy”as he terms it), becomes quite apparent. (14) The landmark paper on deep ecology was written while he was working on Gandhi and Group Conflict, and almost ten years after its precursor Gandhi and the Nuclear Age.

In a now famous debate, that predated deep ecology, with the English philosopher Alfred Ayer on Dutch television in 1971, Naess spelled out his view of what, for him, it means to be a philosopher: “I consider myself a philosopher when I am trying to convince people of nonviolence, consistent nonviolence whatever happens.” He continued:

“I think I believe in the ultimate unity of all living beings. This is a very vague and ambiguous phrase, but I have to rely on it. It is a task for analytical philosophy to suggest more precise formulations. Because I have such principles, I also have a program of action, the main outline of which is part of my philosophy. So I might suddenly try to win you over to consistent nonviolence and to persuade you to join some kind of movement–and this in spite of my not believing that I possess any guarantee that I have found my truths.” (15)

Later on, to push Naess to greater clarity on this, the moderator asked, “Does your offensive nonviolence … imply that you would prefer to be killed by someone else rather than kill someone else?” Naess answered:

“It would be more than a preference, actually. It might be that I would prefer to kill the other person, but I value the preference negatively. Norms have to do with evaluations, with pretensions to objectivity, rather than preferences. Let me formulate it thus: I hope I would prefer to be killed by someone else rather than to kill, and I ought to prefer it.” (16)

While the references at this point are implicit, nevertheless here we have the advaitist (non-dualist) philosopher acting in the world. One could imagine a Gandhi who was formally trained in philosophy making this statement.

However, generally when Arne Naess and his intellectual legacy are discussed, it is in terms of deep ecology rather than Gandhian philosophy. And those who know far more about deep ecology than Gandhian philosophy often attempt to give deep ecology a legitimising lineage by linking it to Eastern spiritual traditions. Some critics frown upon this. The Indian environmentalist scholar Ramchandra Guha, for example, objects to the “persistent invocation of Eastern philosophies” as being the forerunners of deep ecology. Guha points out that philosophies, which are “complex and internally differentiated” are lumped together in a way that makes them spiritual precursors of deep ecology. Further, he complains that the “intensely political, pragmatic, and Christian influenced thinker … Gandhi has been accorded a wholly undeserved place in the deep ecological pantheon”. (17)

Gandhi may not deserve a place in the deep ecological pantheon in terms of Guha’s objections, however through Gandhi’s strong influence on Arne Naess, the “father of deep ecology”, there is a direct link between the Mahatma and the movement. In fact Naess himself admits in a brief third person account of his philosophy that “his work on the philosophy of ecology, or ecosophy, (18) developed out of his work on Spinoza and Gandhi and his relationship with the mountains of Norway”. (19) Reading Naess’s works on Gandhian nonviolence that long predate his ecological work, it is easy to see groundwork for deep ecology.

Naess’s older brothers’ attempts to toughen him up in childhood left him with no doubt that they could be trusted and that they loved him, but it was a tough love devoid of nonsense or sentimentality. This resulted in “a detestation and fear of being influenced by manifestations of spirituality and high-sounding notions.” However, Gandhi’s “Spartan life-style and non-violent militancy could be admired in spite of its background in spiritual metaphysics.” Spinoza too, while indulging in “‘romantic’ notions like perfection and love of God”, was a “tough nut.” This allowed Naess to admire both men of wisdom “without feeling guilt.” (20) Further, he poses the question: “Placing human societies and myself, as I had, within the framework of an essentially homogeneous all-embracing Nature, and admiring and feeling nearness to the small carnivores along the shore, how was it possible for me to come early under the strong influence of Gandhian ethics of non-violence?” He answers his own question by harking back to the many solitary childhood hours he spent observing nature on the shoreline of the sea: “The life to be found in shallow waters may be conceived as essentially peaceful, and favourable to a norm of maximum diversity, richness and multiplicity.” (21)

Gandhi’s Philosophy in Naess’s Ecosophy

“Ahimsa and the Natural World”, artist unknown; courtesy aim-yoga.blogspot.nl

Gandhi experimented with, and wrote a great deal about, simple living in harmony with the environment (22) but he lived before the advent of the articulation of the deep ecological strands of environmental philosophy. His ideas about human connectedness with nature, therefore, rather than being explicit, must be inferred from an overall reading of the Mahatma’s writings. Naess explains that “Gandhi made manifest the internal relation between self-realisation, non-violence and what sometimes has been called bio-spherical egalitarianism”, (23) and points out that he was “inevitably” influenced by the Mahatma’s metaphysics “which contributed to keeping him (the Mahatma) going until his death.” Moreover, “Gandhi’s utopia is one of the few that shows ecological balance, and today his rejection of the Western World’s material abundance and waste is accepted by progressives of the ecological movement”. (24)

While Gandhi allowed injured animals to be killed humanely to save them from unreasonable pain (25) and at times even because they caused undue nuisance, (26) his nonviolence encompassed a reverence for all life. In his office at the Sevagram Ashram, his headquarters during much of the 1930s and 40s, there are a snake transporting cage and a large wooden scissors-like contraption which were used to pick up the reptiles so that they could be taken beyond the perimeter and released as an alternative to killing them. This attitude is mirrored by Naess, and indeed pushed further, when he makes the point that:

“It may be of vital interest to a family of poisonous snakes to remain in a small area where small children play, but it is also of vital interest to the parents of these children that there are no accidents. The priority rule of nearness makes it justifiable for the parents to remove the snakes. But the priority of vital interest of snakes is important when deciding where to establish the playgrounds.” (27)

A review of the Gandhian literature (while keeping in mind the time in which it was written as a reason for anthropocentric expression) readily turns up statements such as: “If our sense of right and wrong had not become blunt, we would recognise that animals had rights, no less than men”, (28) “I do believe that all God’s creatures have the right to live as much as we have”, (29) and “We should feel a more living bond between ourselves and the rest of the animate world”. (30) The clearest indication of Gandhi’s respect for nature, however, comes through his interpretation of the Hindu worship of the cow. Gandhi saw cow protection as one of the most wonderful phenomena in human evolution. “It takes the human being beyond his species. The cow to me means the entire sub-human world. Man, through the cow, is enjoined to realise his identity with all that lives”. (31) “Hinduism believes in the oneness not merely of all human life but in the oneness of all that lives. Its worship of the cow is, in my opinion, its unique contribution to the evolution of humanitarianism. It is a practical application of the belief in the oneness and, therefore, sacredness of all life”; (32) and “my meaning of cow protection … includes … the protection and service of both man and bird and beast.”(33)

Perhaps a better way to illustrate Gandhi’s concerns with the oneness of life is to look at his writings on ahimsa. Usually translated as nonviolence, it can be seen as the fountainhead of Truth–the ultimate goal of life. From his prison cell in 1930, Gandhi wrote to his ashramites that, “without Ahimsa it would not be possible to seek and find Truth. Ahimsa and Truth are so intertwined that it is practically impossible to disentangle and separate them. They are like two sides of a coin or rather a smooth, unstamped metallic disk. Who can say which is the obverse, and which the reverse? Nevertheless, ahimsa is the means, Truth is the end. Means to be means must always be within our reach, and so ahimsa is our supreme duty. If we take care of the means, we are bound to reach the end sooner or later. ” (34)

For Gandhi, ahimsa meant “love” in the Pauline sense and was violated by “holding on to what the world needs”. (35) As a Hindu, Gandhi had a strong sense of the unity of all life. For him nonviolence meant not only the non-injury of human life, but as noted above, of all living things. This was important because it was the way to Truth (with a capital “T”), which he saw as Absolute–as God or an impersonal all-pervading reality, rather than truth (with a lowercase “t”) which was relative, the current position on the way to Truth. These thoughts about realising the self through the realisation of the unity of life are the leitmotif of Naess’s ecosophy.

The Realisation of the Self

Naess had been an admirer of Gandhi’s nonviolent direct action since 1930 and deeply influenced by his metaphysics. When he read Romain Rolland’s Gandhi biography as a young philosophy student in Paris in 1931, he came across Gandhi’s statements on Truth and the essential oneness of all life (Rolland’s book after all is subtitled The Man Who Became One with the Universal Being). Rolland, in trying to explain Gandhi’s ideas of cow protection to an uncomprehending Occidental audience, points out that by it “man concludes a pact of alliance with his dumb brethren; it signifies fraternity between man and beast.” (36) In some of his works, Naess notes that “ecological preservation is nonviolent at its very core” (37) and quotes Gandhi to make the point: “I believe in advaita, I believe in the essential unity of man and, for that matter, of all that lives. Therefore I believe that if one man gains spiritually, the whole world gains with him and, if one man fails, the whole world fails to that extent.” (38) Naess adds, “When the egotism-ego vanishes, something else grows, that ingredient of the person that tends to identify itself with God, with humanity, all that lives.” (39)

As this implies, for Arne Naess deep ecology is not fundamentally about the value of nature per se, it is about who we are in the larger scheme of things. And, as is the case with most philosophers, Naess has always “emphatically endorsed” the Platonic dictum that the unexamined life is not worth living. (40) He stresses the spiritual orientation of deep ecology by noting the identification of the “self” with “Self” in terms that it is used in the Bhagavad Gita (41), that is as the unity which is one, as the source of deep ecological attitudes. In other words, he links the tenets of his approach to ecology with what may be termed self-realisation. And here the influence of the Mahatma is most clearly discernible. Naess notes that while Gandhi may have been concerned about the political liberation of his homeland, “the liberation of the individual human being was his supreme aim”. (42)

The link between self-realisation and Naess’s environmental philosophy can be clearly seen in his discussion of the connection between nonviolence and self-realisation in his analysis of the context of Gandhian political ethics. Naess starts with the “one basic proposition of a normative kind” when investigating Gandhi’s teachings on group conflict: “Seek complete self-realisation” (the “manifestation of one’s potential to the greatest possible degree”). He adds that the “self to be realised is not the ego, but the large Self created when we identify with all living creatures and ultimately with the whole universe.” (43) He then summarises this connection as:

(1) Self-realisation presupposes a search for truth.

(2) In the last analysis all living beings are one.

(3) Himsa (violence) against oneself makes complete self-realisation impossible.

(4) Himsa against a living being is himsa against oneself.

(5) Himsa against a living being makes complete self-realisation impossible. (44)

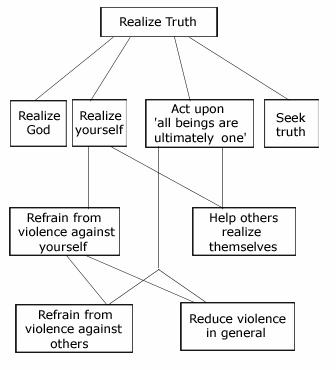

This conceptual construction evolved into ever more complex and graphic presentations. In his 1974 work, Gandhi and Group Conflict, Naess provides various systematisations of Gandhi’s teachings on group struggle where self-realisation is the top norm and which contains the critical hypothesis that all living beings are ultimately one, such as that in Figure 1. (45)

Figure One

In a discussion with David Rothenberg over human destruction of the environment without adequate reason (for example where a parent kills the last animal of a species to save his or her child from its attack), Naess is asked whether protection of nature should occur because we should not think only of ourselves or because natural things are part of us also. Naess refuses to separate the two approaches. He answers with another allusion to Gandhi: “When he was asked, ‘How do you do these altruistic things all year long?’ he said, ‘I am not doing something altruistic at all. I am trying to improve in Self-realization’.” (46) There need be no divide between the intrinsically valuable and the useful. And, in a Gandhian way of feeling rather than intellectualising, he adds: “… if you hear a phrase like, ‘All life is fundamentally one,’ you should be open to tasting this, before asking immediately, ‘What does this mean?’” (47)

Naess notes that Gandhi had a rare combination of qualities that included humility towards factual truth, an awareness of human fallibility and the knowledge that at any time he might be proved to be wrong about a factual situation. This never led to inaction, but, in what Naess saw as an “extremely rare” combination, was balanced by his activism. (48) While Gandhi was an activist rather than merely a contemplative philosopher, he certainly would not have welcomed practices such as ecotage–the disabling of logging equipment and the illegal spiking of trees so that they cannot be logged economically even if it can be argued that because all living beings are one, fighting to preserve nature is an act of self-defense. Arne Naess is a firm believer in revolutionary nonviolence. He reminds us that:

“Gandhi supported what he and others called ‘nonviolent revolution,’ making extensive use of direct actions. But it was a step-by-step revolution. He insisted that one step at a time ‘is enough for me.’ If, and only if, the Gandhian terminology is accepted, then I would find it adequate to say that the deep ecology movement is revolutionary. If an action has to be violent in order to be called ‘revolutionary,’ then the movement is not revolutionary.” (49)

Conclusion

This Gandhian revolutionary nonviolence, without the hyphen, (50) pervades Ecosophy, and this in turn provides the philosophical underpinning for much of the other writings on deep ecology. In other words, even if one’s interest in Arne Naess is because of his work on deep ecology, his philosophy of deep ecology itself can be better understood by going back to Gandhi and seeing the influence Gandhi had on Naess and consequently on his environmental writings. (51) And if one wants to understand Gandhian philosophy a little better, it may be worth the effort of tracking down Arne Naess’s relevant publications now that he can no longer be spoken to in person.

Endnotes: (TW)

(1) Leading ecological philosopher, George Sessions claims that he may well be recognized as one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century. See his chapter, “Arne Naess and the Union of Theory and Practice”, in Alan Drengson and Yuich Inoue (eds.), The Deep Ecology Movement: An Introductory Anthology, Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 1995, pp.54-63, at p.63. ‘Deep ecology’ is a philosophy based on the equal worth of all human and non-human life, including plant life and the environment. Non-human life is held to have intrinsic value independent of its usefulness to humans. The main practical implications of deep ecology can be summarised as (a) wilderness preservation, (b) human population control, and (c) simple living (or treading lightly on the planet).

(2) Arne Naess, Gandhi and Group Conflict: An Exploration of Satyagraha, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1974.

(3) Arne Naess, Gandhi and the Nuclear Age, Totowa, NJ: The Bedminster Press,1965.

(4) Arne Naess, Communication and Argument: Elements of Applied Semantics, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1966.

(5) Personal communication with Hanna Weber, October 1997. Used with permission.

(6) Arne Naess, “How My Philosophy Seemed to Develop”, in Andre Mercier and Maja Svilar (eds.), Philosophers on their Own Work, Bern: Peter Lang, 1982, vol.10, pp.209-226 at p.210.

(7) Naess, “How My Philosophy Seemed to Develop”, pp.212-213.

(8) Arne Naess, “Modesty and the Conquest of Mountains”, in Michael Tobias (ed.), The Mountain Spirit, New York: Overlook, 1979, pp.13-16 at p.14.

(9) See the introductory chapter to Peter Reed and David Rothenberg (eds.), Wisdom in the Open Air: The Norwegian Roots of Deep Ecology, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

(10) See Nina Witoszek, “Arne Naess and the Norwegian Nature Tradition”, in Nina Witoszek and Andrew Brennan (eds.), Philosophical Dialogues: Arne Naess and the Progress of Ecophilosophy, Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1999, pp.451-465.

(11) David Rothenberg, Is it Painful to Think?: Conversations with Arne Naess Father of Deep Ecology, Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1993, pp. 91-101.

(12) See Arne Naess , “Environmental Ethics and Spinoza’s Ethics: Comments on Genevieve Lloyd’s Article”, Inquiry, 1980, vol.23, no.3, pp.313-325; and Peder Anker, “Ecosophy: An Outline of its Megaethics”, The Trumpeter,1998, no.15, no.1.

(13) Arne Naess , “The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement. A Summary”, Inquiry, 1973, vol.16, no.1, pp.95-100.

(14) Much of the following material is a summarised version of parts of the chapter on Arne Naess in Thomas Weber, Gandhi as Disciple and Mentor, Cambridge/New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2004/2007, pp.191-202.

(15) Arne Naess, Alfred Ayer and Fons Elders, “The Glass Is on the Table: The Empiricist versus Total View”, quoted in Witoszek and Brennan (eds.), Philosophical Dialogues, pp.10-28 at p.14.

(16) Naess et al, “The Glass Is on the Table”, p.22.

(17) Ramchandra Guha, “Radical American Environmentalism and Wilderness Preservation: A Third World Critique”, in Witoszek and Brennan (eds.), Philosophical Dialogues, pp.313-324, at p.317.

(18) Naess calls his philosophy, which is profoundly concerned with ethics and the idea of self-realisation, “Ecosophy T”. The word is a combination of the Greek words oikos (household) and sophia (wisdom). The “household” is the planet. The “T” stands for Tvergastein, where he has done his most productive philosophical thinking and writing, and it implies that it is only one of several possible formulations for an ecological philosophy.

(19) Bill Devall and George Sessions, Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered, Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 1985, p.225.

(20) Naess, “How My Philosophy Seemed to Develop”, pp.213-214.

(21) Naess, “How My Philosophy Seemed to Develop”, p.224.

(22) See Shahed Power, “Gandhi and Deep Ecology: Experiencing the Nonhuman Environment”, unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Environmental Resources Unit, University of Salford (1991), pp.12-124.

(23) Arne Naess, “Self-Realisation: An Ecological Approach to Being in the World”, in John Seed, Joanna Macy, Pat Fleming and Arne Naess, Thinking Like a Mountain: Towards a Council of All Beings, Philadelphia: New Society Publishers, 1988, p.26.

(24) Naess, Gandhi and Group Conflict, p.10.

(25) See among others letters, Gandhi to Purushottam Gandhi, 12 May 1932, concerning the mercy killing of an ailing calf in the ashram.

(26) “Right to Live”, Harijan, 9 January 1937.

(27) Arne Naess, “Identification as a Source of Deep Ecological Attitudes”, in Michael Tobias (ed.), Deep Ecology, San Diego: Avant Books, 1984, pp.256-270 at pp.266-267.

(28) “Harijans and Pigs”, Harijan, 13 April 1935.

(29) “Right to Live”, Harijan, 19 January 1937.

(30) “Our Brethren the Trees” Young India, 5 December 1929.

(31) “Hinduism”, Young India, 6 October 1921.

(32) “Why I Am a Hindu”, Young India, 20 October 1927.

(33) “Speech at All-India Cow-Protection Conference, Bombay”, Young India, 7 May 1925.

(34) M.K. Gandhi, From Yeravda Mandir, Ahmedabad: Navajivan,1932, p.6.

(35) Gandhi, From Yeravda Mandir, p.5.

(36) Romain Rolland, Mahatma Gandhi: The Man who Became One with the Universal Being, London: Allen and Unwin, 1924, p.22 in the 1968 reprint by the Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, New Delhi.

(37) Naess, “Self-Realisation”, p.25.

(38) See Naess, Gandhi and Group Conflict, p.42. For the original quotation see “Not Even Half-Mast”, Young India, 4 December 1924.

(39) Naess, Gandhi and Group Conflict, p.38.

(40) Naess, “How My Philosophy Seemed to Develop”, p.215.

(41) See chapter 6, verse 29, which states that one disciplined by yoga sees the Self in all beings, and all beings in the Self. See Naess, “Identification as a Source of Deep Ecological Attitudes”, p.260. See also Knut A.Jacobsen, “Bhagavadgita, Ecosophy T, and Deep Ecology”, Inquiry, 1996, vol.39, no.2, pp.219-238.

(42) Naess, “Self-Realisation”, p.24.

(43) Naess, “How My Philosophy Seemed to Develop”, p.225.

(44) Adapted from Naess, Gandhi and the Nuclear Age, pp.28-33.

(45) Naess, Gandhi and Group Conflict, p.55.

(46) Rothenberg, Is it Painful to Think?, pp.141-142.

(47) Rothenberg, Is it Painful to Think?, p.151.

(48) T.K.Mahadevan (ed.), Truth and Nonviolence: A UNESCO Symposium on Gandhi, New Delhi: Gandhi Peace Foundation, 1970, pp.70, 85-86.

(49) Arne Naess “Is the Deep Ecology Vision a Deep Vision or is it Multicolored like the Rainbow? An Answer to Nina Witoszek”, in Witoszek and Brennan (eds.), Philosophical Dialogues, pp.466-472 at p.468.

(50) For Naess, “non-violence” (with the hyphen) is the broader category that does not permit the doing of harm to humans or animals. “Nonviolence” (without the hyphen) is the technical term for a subcategory of non-violence, the principled form as practiced by Mahatma Gandhi (See Arne Naess, “Letter to Dave Foreman, 23 June 1988, in Witoszek and Brennan (eds.), Philosophical Dialogues, pp.225-231 at p.227). However, Gene Sharp, the main theorist of practical rather than principled Gandhian nonviolence, also spells his form of social action without a hyphen, a hyphen it should have in Naess’s classification.

(51) As noted above, Arne Naess spent much of his time spreading the word of Gandhi directly as well as indirectly through his own writings on other matters. But perhaps his indirect dissemination of Gandhian philosophy is even more extensive than hinted at here. Johan Galtung, the “Father of Modern Peace Research”, who gave us the very Gandhian concept of “structural violence”, may have achieved more than Naess in directly popularising the Mahatma and his philosophy, but it must be remembered that it was Arne Naess who introduced the young Galtung to Gandhi in the first place. See Weber, Gandhi as Disciple and Mentor, p. 209.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Thomas Weber is Honorary Associate of the Politics and International Relations Program at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. He has been a regular visitor to India, and researcher on Gandhi, since 1975, and in 1983 re-walked the route of Gandhi’s Salt March from Sabarmati to Dandi. His Gandhi and peace/nonviolence related books include Going Native: Gandhi’s Relationship with Western Women; The Shanti Sena: Philosophy, History and Action; Gandhi, Gandhism and the Gandhians; Gandhi as Disciple and Mentor; edited with Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan; Nonviolent Intervention Across Borders: A Recurrent Vision; On the Salt March: The Historiography of Gandhi’s March to Dandi; Gandhi’s Peace Army: The Shanti Sena and Unarmed Peacekeeping; Conflict Resolution and Gandhian Ethics; and Hugging the Trees: The Story of the Chipko Movement. This is a revised, expanded version of an article that first appeared in Journal of Peace Research; Vol. 36, No. 3, May 1999; courtesy of Dr. Weber and mkgandhi.org