Book Review: A Guide to Civil Resistance

by George Lakey

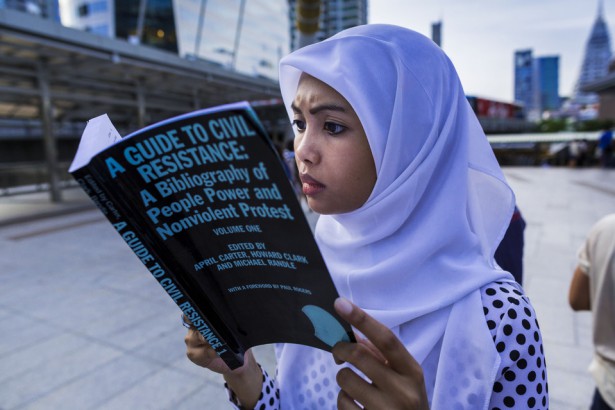

Woman protesting Thai coup, June 2014; photograph courtesy wagingnonviolence.org

I first encountered Gene Sharp when he was a young man in jeans and sneakers, working in a research institute affiliated with the University of Oslo. Not guessing that he would become a mentor of mine, I met him because one of my Norwegian professors sent me to him. Gene had already served time in a U.S. federal prison for draft resistance and then joined the War Resisters’ International [WRI] Peace News staff to report on activism in the United Kingdom. Now he was in a small cubicle with a typewriter, analyzing the Norwegian resistance to Nazi German occupation during World War II. A half century later, in 2011, Foreign Policy would list Gene among the 100 most influential thinkers in the world.

Gene told me that even in his young adult years with the radical A.J. Muste in New York and then working with Peace News in London, he’d heard amazing stories about people’s nonviolent resistance to oppression. The stories fed his intense curiosity: How can people coerce an opponent nonviolently, when we all know that “only violence can be powerful.” Happily, Gene then studied political science at Oxford University and there he nailed part of the answer to his question, arguably the hardest part. His answer included channeling Machiavelli, and he’s been quoting Machiavelli ever since.

In that same period, April Carter was getting herself arrested in the direct action wing of Britain’s 1950s Ban the Bomb movement. Michael Randle was helping that movement go to a mass level by organizing the influential, anti-nuclear, Aldermaston [U.K.] marches, held every Easter from 1959 through the 1960s. They were curious about impact, so along with the thrill of participating in their country’s primary social movement, they were asking themselves the question asked by all real craftspeople: How does this thing work and how can it work better?

When April and Michael connected with Gene Sharp they recognized common ground: There’s nothing so practical as a good theory. Guatemala’s history illustrates this old maxim. In 1944 university students initiated a national nonviolent uprising against Jorge Ubico, “the Iron Dictator of the Caribbean.” They were playing catch-up with the Salvadoran students next door, who earlier nonviolently overthrew their own dictator after others, using armed struggle, had failed. The Guatemalans succeeded in sending Ubico packing, and ushered in a new era of democracy. What they did not do was to “make theory” out of their experience and that of their Salvadoran comrades; they didn’t make new generalizations about what we now can call “a force more powerful.”

The Guatemalans were therefore unable to prepare a nonviolent defense against threats to their new democracy. The United Fruit Corporation, a U.S. corporation with extensive operations in Guatemala, became unhappy with the government’s decision to force the company to sell its unused plantation lands to the government, at the tax-assessed value of the land. The government’s plan was to distribute the land to hungry farmers.

CIA director Allen Dulles, with the support of his brother who headed the U.S. State Department and had a financial interest in United Fruit, organized a military coup to overthrow the democratic government of Guatemala. Facing no organized nonviolent resistance, in 1954 the coup succeeded and led to decades of terrible suffering for the people.

I caught up with the nonviolent story of the Guatemalan students in the late 1960s, the period when young Howard Clark was starting his own activism in Britain. Over time, Howard gravitated toward activist journalism, as well as edgy nonviolent projects. Howard found that he, too, wanted to hurry up the research that would help all activists to become more effective. I knew Howard and Michael Randle mostly through our work with WRI.

In 2006, Howard and Michael teamed up with April Carter to produce what they (and Gene Sharp and I) all wished we’d had as young activists — a book called People Power and Protest Since 1945: A Bibliography of Nonviolent Action. [See Reference note at the end for full details.] At last there were, in one place, leads to literature that can help everyone make maximum sense out of their experience. The book invites the learning curve of our dreams, an overlooked source of hope.

Carter, Clark and Randle’s book came just in time to support a new generation of activists and scholars who were wondering why the global economic justice movement unveiled in the 1999 Battle of Seattle didn’t reveal more of a learning curve. The sources their book points to also help us understand the complex “color revolutions” of the early 2000s and the mass struggles in the Global South.

When we first met, Gene Sharp was the only person in the world researching nonviolent action full-time. Since then a host of scholars and writers have covered struggles from environmental to human rights to economic justice to the Arab Awakening. The usefulness of the new literature moved April, Howard, and Michael to enlist help and publish a new, expanded, two-volume edition of their 2006 book, now titled A Guide to Civil Resistance: A Bibliography of People Power and Nonviolent Protest. [See Reference note at the end for full details.] It took two volumes to take account of the accelerating use of nonviolent action all over the world; the first volume was released in 2013 and the second in 2015. Because the guide’s primary interest is in movements rather than specific campaigns, it includes literature sometimes left out by the campaign-specific Global Nonviolent Action Database, linked here.

The compilers give a huge boost to the readers by annotating all of the books and articles. The reader wanting to know more about the Palestinian opposition to the Israeli occupation, for example, or Africans’ resistance to authoritarian governments, can choose where to plunge in without wandering in the weeds of the Internet with its frequent appearance of unreliable or just plain wrong accounts. The first volume of the guide has been made available for free online.

The compilers also give helpful background paragraphs before each national struggle and even before particular movements like the Spanish and Greek anti-austerity protesters (Indignados), the anti-corruption campaigns in India, and the LGBT movement in the West.

If you wish to catch up with an overview of nonviolent struggles on multiple continents, you can skip over the sources in the book and get an amazing big picture by reading the contextualizing paragraphs that begin each section. No one ever again has to imagine that nonviolent action is simply “about Gandhi and King.”

Thanks to Howard Clark, who unexpectedly died in 2013, and April Carter and Michael Randle, it has never been so easy for us to think globally, while acting locally.

REFERENCE: April Carter, Howard Clark and Michael Randle (eds.) Foreword by Paul Rogers, A Guide to Civil Resistance: Volume 1; A Bibliography of People Power and Nonviolent Protest London: The Merlin Press, 2013; and April Carter, Howard Clark and Michael Randle (eds.) Foreword by Paul Rogers, A Guide to Civil Resistance: Volume 2; A Bibliography of Social Movements and Nonviolent Action, London: The Merlin Press, 2015.

EDITOR’S NOTE: George Lakey co-founded Earth Quaker Action Group which won its five-year campaign to force a major U.S. bank to give up financing mountaintop removal coal mining. Along with college teaching he has led 1,500 nonviolence workshops on five continents, and activist projects on local, national, and international levels. Among many other books and articles, he is author of “Strategizing for a Living Revolution” in David Solnit’s book Globalize Liberation (City Lights, 2004). His first arrest was for a civil rights sit-in and more recently, with Earth Quaker Action Team, while protesting mountain top removal coal mining. Please see his important article on nonviolent training also posted here. Article is courtesy wagingnonviolence.org, and Creative Commons agreement.