Satyagraha and Interpersonal Conflict Resolution

by Thomas Weber

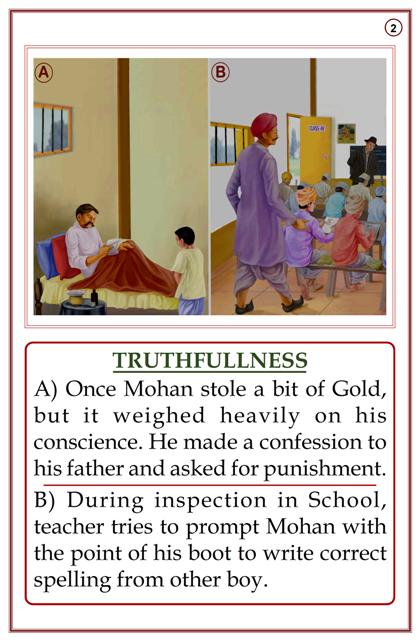

Cartoon poster courtesy mkgandhi.org

Satyagraha, as used in interpersonal conflicts, often depends on the degree to which its values have been internalised rather than on a conscious adoption of tactics. Gandhi claimed that “there is no royal road” to achieve this. It will only be possible “through living the creed in your life which must be a living sermon”. This “presupposes great study, tremendous perseverance, and thorough cleansing of one’s self of all impurities”, which in turn requires working through “a wide and varied experience of interior conflict”. These interior conflicts, for example the questioning of one’s own motives and prejudices, the sincere attempt to see if in fact the other’s position is nearer the truth, and if need be admitting one’s errors, are in some measure alternatives to wider conflicts.

The critics of nonviolence often attack the pacifist approach or justify not trying nonviolent solutions by posing the hypothetical case in which the satyagrahi is either himself attacked, or is witness to an attack upon another. It is unlikely that such an eventuality will occur in the lifetime of average individuals; most human conflicts take place in quite different circumstances. Lanza del Vasto, therefore, warns against using such “extreme, exceptional, and overpowering” imaginary circumstances for formulating general rules or drawing conclusions from them concerning legitimacy of action. The striving for nonviolence, instead of planning for such possible eventualities, accepts that if they did occur they would be still taken care of somehow (just as if they had been planned for), while during the rest of one’s life, other, almost daily conflicts could be solved in more cooperative ways.

The rule for reconciling the duty of resistance to evil on the one hand and of nonviolence (ahimsa) on the other, according to Gandhi, “is that one should ceaselessly strive to realise Ahimsa in every walk of life and in a crisis act in a manner that is most natural to him. The result will be nonviolence to the extent to which he has successfully striven.” Eventually such conscious striving will be internalised and “spontaneous reactions in a crisis will be nonviolent”.

In the language of Christ or Gandhi, Lanza del Vasto explains, if we are able to control our actions we should, or if we have internalised nonviolence sufficiently we will, if struck on one cheek turn the other. The returning of evil for evil, rather than ending evil, doubles it. No one, he claims, is so bad as to continue “taking advantage indefinitely of the opening given to him and his own impunity”, and even those mad with rage have been known to stop “as if thunderstruck when you do not retaliate”. The reason for behaving this way, for accepting self-suffering rather than retaliating, is that “your enemy is a man”. In fights the enemy is generally dehumanised, is seen as a beast or monster, and “that is the moment and not now when you must stick to the hard truth that he is a man, a man like yourself”, and “if he is a man, the spirit of justice dwells in him as it dwells in you”.

Where the defence of a third party is in question Gandhi does not take as narrow an approach as one of his mentors, Tolstoy, did. Tolstoy was firm in his belief that the justification of violence used against a neighbour for the sake of defending another man against worse violence is always incorrect, because in using violence against an evil which is not yet accomplished, it is impossible to know which evil will be greater.

Gandhi, however, insisted that injustices had to be fought and his intolerance of cowardice prompted him to explain that self-defence and defence of third persons, even if violence is involved, “is the only honourable course where there is unreadiness for self-immolation”. He was even willing to go as far as to claim that nonviolence may be compatible with killing, but never with hating: “Even manslaughter may be necessary in certain cases. Suppose a man runs amuck and goes furiously about sword in hand, and killing anyone that comes in his way, and no one dares to capture him alive. Anyone who dispatches this lunatic will earn the gratitude of the community and be regarded as a benevolent man.”

When Gandhi was asked by his eldest son what action he should have taken had he been present when Gandhi was almost fatally assaulted in 1908, whether he should have run away and seen his father killed or whether he should have used the physical force that he wanted to use in defense of Gandhi, he was informed that “it was his duty to defend me even by using violence”.

Gandhi was fond of pointing out that satyagraha can be used in broader fields, as it can in the everyday domestic situation; however, he was careful to add “that he who fails in the domestic sphere and seeks to apply it only in the political and social sphere will not succeed”.

Those who harbour feelings of fear will always be potential enemies. Fear is a deep-seated emotion that is hard to fight. Others will easily see through our false impression of fearlessness. To achieve internalised nonviolence we must conquer fear and cultivate trust. As the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess observes, personal relationships are an area where this substitution can be commenced as a first step towards integrating it as a lifestyle.

Most conflicts are in the order of “zero-sum”, a theoretical model in which both parties have the desire to dominate. Often this is born of fear or insecurity, the feeling that if one yields, or shows trust, advantage will be taken of them. The function of nonviolent resistance in these conflicts is never to harm the opponent or impose a solution on them against their will, but to help both parties into “a more secure, creative, happy and truthful relationship”. This can be achieved by remaining nonviolent despite the hardships and apparent losses, and by respect for personality, good-will, acts of kindness, adherence to truth, disciplined order, a belief that human unity and underlying similarities are more enduring and important than human differences, and a steady series of deeds in accord with that belief.

In dyadic conflicts, of which domestic quarrels are a good example, “non-cooperation, civil disobedience of the orders of the offender if he happens to be in exercise of authority, suffering of hardships that came as a result of this resistance, fasting, etc.” may be employed, but the chief measures to be used will be persuasion and discussion. The Gestalt therapist Fritz Perls claims that in the world a peculiar polarity exists between listening and fighting: “People who listen don’t fight, and people who fight don’t listen.” With more listening he believes that the number of hostilities would greatly diminish. Listening and seeing the other’s point of view, however, must be more than an intellectual exercise, it must contain a sincere desire to understand, it must have empathy. This clarifies the issues and aids the search for truth.

The genuine quest for truth in conflict situations has the byproduct of changing perceptions as the circumstances and the underlying causes become more apparent, for “the action of an individual depends directly on the way in which he perceives the situation.” This means that satyagrahis cannot remain rigid in their attitude but must, while hoping to win the opponent over, be willing to change their own attitudes with the dictates of the unfolding facts.

As mentioned, the resolution of interpersonal conflicts along Gandhian lines depend to a large degree on how far the principles of satyagraha have been internalised; however, there are various techniques that can be learned which will aid in the cooperative solution of such conflicts. These techniques are in keeping with the Gandhian ideal of nonviolence, that is, treating the other as a “you” rather than as an “it”.

When interpersonal conflicts arise, whether they be between parties having differing degrees of authority (for example, parent/child in the home or teacher/student in the school) or between parties having theoretically equal power (friends, marriage partners, etc.) the general ways of bringing conflicts to an end are for the parties to attempt to impose their will on each other, for authority figures to exercise their authority, or for one party to give in. The first of these “zero-sum” approaches (authoritarian) may produce resentment and hostility in the loser, provide them with little motivation to carry out the solution, requires heavy enforcement, inhibits the growth of self-responsibility, self-discipline and creativity, fosters dependence and submission (mainly out of fear), and may make the winner feel guilty.

The second approach (permissiveness) is of the “Okay-you-win, I-give-up” method of dealing with conflict. In the winner this may foster selfishness and reduce their respect for the loser. For the loser it fosters resentment towards the winner, makes them feel guilty about not getting their needs met and may require the loser to be pushed into an authoritarian approach. In these conflict situations those without power or authority learn to cope by rebelling, retaliating, or through dishonesty (eg. lying, cheating, blaming others), and also cope by submitting or even fantasizing and regressing.

The use of these zero-sum methods will generally have the outcome of solving the manifest conflicts where the parties have unequal power. Where the parties are of relatively equal power zero-sum methods often result in bitter stalemates making cooperative methods of solving disputes in these circumstances perhaps even more important. Cooperative approaches to conflict solution avoid these negative outcomes.

A technique, appropriate in cases where personal needs rather than values or beliefs are the focus of the conflict, which allows one to express underlying conflicts is called the “I-Message”. In interpersonal conflict the initial response is often destructive, taking the form of blame which generally obscures the real issues underlying the conflict. Reformulating negative statements of blame into “I-Messages” (which explain the feelings of the speaker as the result of unacceptable behaviour by the other and give the speaker’s perception of the consequences of the behaviour to themselves, rather than the more usual blaming of the other for unacceptable behaviour and its consequences), can aid the clarification of the issues and steer the conflict onto a constructive and cooperative path. “You-Messages” that are very often sent, unlike “I-Messages”, tend to provoke resistance and rebellion.

Another technique that can clarify the real issues in an interpersonal conflict and thus aid its solution is the role-reversal technique of switching viewpoints where each party honestly tries to argue for the other’s viewpoint, while the other listens. These techniques are applicable in domestic situations or with friends and neighbours where there is a sufficient degree of rapport.

In line with Gordon Rapoport’s insistence on the importance of being correctly heard and understood, and Gandhi’s insistence on establishing the truth, the techniques of “active-listening” and “mirroring” could be used until hearing what the opponent in a conflict is saying becomes second nature. The essence of active listening is mirroring back what has been said. This assures the accuracy of listening and also “assures the sender that he has been understood when he hears his own message fed back to him accurately”. Active listening can help to solve immediate interpersonal conflicts or it can be used by a third party to help one of the antagonists in a conflict situation clarify their own feelings and think creatively about possible solutions.

Where active listening is used to reach a solution to an immediate interpersonal conflict its effectiveness excludes conflicts over the collision of values or beliefs. In these cases it is hard to point to tangible and concrete effects of the annoying behaviour of one party on the other. (It should be noted, however, that authoritarian and permissive win/lose methods also have limited success in truly solving these types of problems.) One must live and be a model for one’s own value system while trying to become more accepting. Gordon suggests, as a way of seeking truth, that in conflicts over values or beliefs the individual has a duty to honestly ask themselves “why do I find it so difficult to accept someone who chooses to be different from me?”

Of course Gandhi did not know of these techniques; however, he was fond of emphasising the need for caring and cooperative interpersonal relations that these techniques may aid to achieve. He firmly believed that the home was the training ground of satyagraha. The world in microcosm and how we reacted to aggression from strangers or handled our disagreements depended upon that training. The care and attention paid to small seemingly unimportant conflicts is as important as that given larger disputes, “For it will be by those small things that you shall be judged.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Thomas Weber is Honorary Associate of the Politics and International Relations Program at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. He has been a regular visitor to India, and researcher on Gandhi, since 1975, and in 1983 re-walked the route of Gandhi’s Salt March from Sabarmati to Dandi. His Gandhi and peace/nonviolence related books include Going Native: Gandhi’s Relationship with Western Women; The Shanti Sena: Philosophy, History and Action; Gandhi, Gandhism and the Gandhians; Gandhi as Disciple and Mentor, edited with Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan; Nonviolent Intervention Across Borders: A Recurrent Vision; On the Salt March: The Historiography of Gandhi’s March to Dandi; Gandhi’s Peace Army: The Shanti Sena and Unarmed Peacekeeping; Conflict Resolution and Gandhian Ethics; and Hugging the Trees: The Story of the Chipko Movement. Article courtesy of Dr. Weber and mkgandhi.org.