Growing Up with Gandhi: Memories of My Childhood in Gandhi’s Ashrams

by Narayan Desai

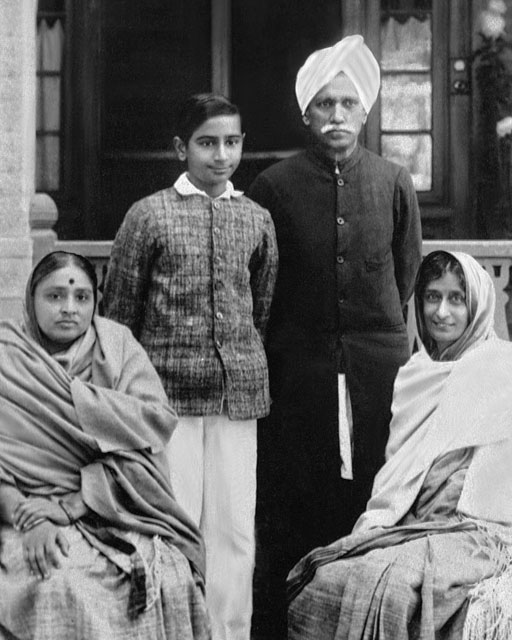

Editor’s Preface: Narayan Desai (b. 1924) is the son of Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s chief secretary until 1942. He is the founder of the nonviolence training center, the Institute for Total Revolution, and the author of a four volume biography of Gandhi among other works. He has been awarded both the Jamnalal Bajaj Award and the UNESCO Madanjeet Singh Prize for his work in nonviolence and pacifism. JG

The Satyagraha Ashram of Mahatma Gandhi stood on the bank of the broad Sabarmati River, across from the city of Ahmedabad. “This is a good spot for my ashram,” Bapu used to say. All of us in the ashram called him Bapu, or Father. He added, “On one side is the cremation ground. On the other is the prison. The people in my ashram should have no fear of death, nor should they be strangers to imprisonment.” Indeed, my earliest memories of Bapu are intertwined with those of Sabarmati Prison. Bapu would go for a walk each morning and evening. He would put his hands on the shoulders of those to either side. These companions would be his “walking sticks.” We children were always given first choice for this job. Whether his human walking sticks were really any help to him, perhaps only Bapu could say. But as for us, being chosen always made us swell with pride. In fact, in our eagerness to be chosen Bapu’s “sticks”, we would sometimes clash.

Each morning and evening, we would start out from Bapu’s room, walk to the main gate of Sabarmati Prison, and then turn back. His pace was usually too brisk for us. But as we neared the prison gate—if he wasn’t engaged in serious discussion—he would almost run the last fifty yards or so. Sometimes we would remove Bapu’s hands from our shoulders and dash to the gate. Sometimes Bapu would put his entire weight on our shoulders, lift his feet off the ground, and shout, “Come on, Boss, let’s see how you run!”

Bapu used to nickname those he cared about, often bestowing more than one name. Among the many showered on me was “Boss.” Of course, he meant it in fun, and at that age it certainly never aroused in me the quality implied.

Bapu kept close contact with every person in the ashram. He maintained a deep interest in their diet and living conditions. When they were ill, he would visit them twice a day. In every aspect of their individual or collective discipline, Bapu guided them directly or indirectly.

The ashram had its rules—strict always, often stern, sometimes harsh as well. Bapu made these rules. His word was final in how they were applied. In these ways, Bapu could be seen as the patriarch of a large, extended family. But my personal view of Bapu—and I believe the view of the other ashram children—was completely different. For us children, he was never the stern disciplinarian, never the dictator. To us, he was above all simply a friend.

Let’s take the example of the dining hall. The rule was that all the ashramites eat their meals in this hall. The ringing of the ashram bell would call us to the meal. At the second ringing of the bell, the dining hall doors closed. The third ringing began the prayers. One time, I was late getting to the dining hall. Just as I was climbing the stairs, the bell rang for the second time. The dining hall doors slammed shut. Now, what child anywhere on earth has adhered to the rules and regulations regarding meals? Just the same, a closed door now stood between my food and me. I began imagining the scene on the other side of the door. People would be sitting on the floor in four rows. Their plates would have been filled with rice, vegetables, milk, and slices of yeast bread. My mother, working in the kitchen, would be worrying over my absence. Bapu, sitting near the door, would be looking around at everyone with a smile.

I don’t remember whether it was someone else’s idea or my own, but standing at the closed door, I began to sing. Open the gates, O Lord, open the gates of your temple. All was quiet in the dining hall, so my young voice carried inside. Bapu burst into laughter, and the doors swung open!

I also had a personal taste of Bapu’s style of fighting.

One time, a friend of our family sent some toys for me from Bombay. There were plenty of places to play in the ashram, but few toys. So we ashram children were always happy to get them. But to our misfortune, the toys sent for me were foreign-made. At that time, the national boycott of foreign goods was in full swing. Bapu had himself initiated this, to stop the draining of India’s wealth by industrial nations. So when the toys arrived, Bapu confiscated them before they ever got to us.

Our “Secret Police” informed us that some toys had been sent from Bombay for Babla (my nickname), and that Bapu had hidden them. We prepared to take up arms against this gross injustice. To launch our struggle, we decided to send a deputation to Bapu. Since the toys had come in my name, I was selected the spokesman. Our delegation arrived at Bapu’s cottage. My father, who was Bapu’s chief secretary, was sitting as usual at Bapu’s side, writing. Other ashramites were there as well.

I fired the first volley. “Is it true that some toys have come from Bombay?” It helps to extract a confession of fact from the opponent before the war commences in earnest.

Bapu was just then busy writing. But he looked up from his work and said, “Oh, it’s you, Babla. Yes, it’s true about the toys.”

“Where did you put my toys?” In the second volley was the inquiry into the whereabouts of the goods.

“They’re over there on the shelf,” said Bapu, pointing. The goods were not hidden at all. And there was a whole basketful of them!

“Hand over those toys!” When justice is on your side, why beat around the bush?

But then Bapu began to set out his own argument. “You know the toys are foreign-made, don’t you?” If Bapu himself had set up the boycott of foreign goods, how could ashram children play with foreign-made toys? That was Bapu’s line of reasoning. But at our age, how could we understand such things?

“I know nothing about Indian or foreign. I only know they’re my toys, and they’ve been sent here for me. So you have to let me have them.” I asserted my rights. I was sure Bapu would not deny me my rights.

But suddenly Bapu gave the argument a new twist. “Can we play with foreign-made toys?” In that word “we,” Bapu played his trump card. In just one sentence, Bapu had placed me and him on the same side of the fence. As I was losing my right to play with those toys, Bapu was giving up his own. And the moment I was shown that my opponent had shared that right, the responsibility he had taken on became mine also.

Where did our arguments vanish? Where could our delegation make its stand? When the enemy himself sides with you, the contest is completely unbalanced.

“We have ourselves launched the boycott of foreign goods, and if we play with foreign goods here at home . . . ” But Bapu didn’t have to pursue the argument. Seeing their spokesman unnerved, the other members of the delegation were already slipping away.

If Gandhi was Bapu— “Father”—then what did I call my own father? I called him “Uncle.”

Uncle’s work as chief secretary entailed going through Bapu’s mail, writing some replies, dealing with people who had come to talk with Bapu, taking notes of important discussions and meetings, and writing or translating articles for Bapu’s weeklies. Besides these standard assignments, he might be preparing a book, writing articles for dailies, or addressing public gatherings.

Work with Bapu was an extraordinarily heavy load. For years on end, I watched Uncle work at least fifteen hours a day. Yet in the twenty-five years Uncle was with Bapu, Uncle took off from work only twice. These were the two times he was sick. In all those years, he took no other time off—no Sunday, no holiday, no summer vacation. What was amazing was how well Uncle coped with this load. The key to this feat was the complete identification he had developed with Bapu. In this relationship was a rare fusion of devotion to a superior, and allegiance to a colleague. Uncle had an independent personality completely different from Bapu’s. Yet the degree of psychic unity between the two was astonishing.

In writing, Bapu was pragmatic, a master of brevity. Uncle’s personal writing, on the other hand, was lavishly lyrical, full of lovely figures of speech. And yet Uncle in his articles had mastered Bapu’s style. Readers of Bapu’s weeklies would often comment that, without the initials at the end of the articles, they wouldn’t know whether the author was M. D. (Mahadev Desai) or M. K. G. (Mohandas Karamchand) Gandhi.

Whatever articles Uncle wrote for the weeklies would always first go to Bapu for approval. Bapu would go through them carefully and correct them if needed. But many times Bapu would find an article so close to his own thinking, he would initial the article himself and it would be published as his.

Uncle did not know shorthand. But his speed in writing things down was extraordinary. He would shorten some words. But he would not miss a single word of Bapu’s.

But simple speed in transcription was not all that was required of Uncle in taking notes of Bapu. Bapu’s speeches were always delivered impromptu, and they were not always organized or coherent. There was a natural flow, but no order. Uncle would organize the speech as he wrote it down. Sometimes even Bapu’s colleagues couldn’t figure out what Bapu had said. But they would comfort themselves, saying, “We will know once we get Mahadev’s notes.”

I once witnessed a remarkable example of the psychic unison between Bapu and Uncle. The two were standing in front of Bapu’s cottage, talking. Suddenly Bapu said, “Mahadev, take this down.” Bapu began dictating, and Uncle, still standing, started writing. I was standing beside the two and watching. After a while, I noticed that Uncle’s writing had pulled ahead of Bapu’s dictation. Before Bapu could say what he wanted to, Uncle would figure out what it was and write it down. But at one point, Bapu dictated a word different from what Uncle had set down. So Uncle interrupted him. “Bapu, wait, I’ve written a different word here. Why did you use this other word instead?” Bapu was somewhat amused. But he too was particular about words. “Mahadev, how could you use this other word? I would never use any word but the one I dictated.” There followed a discussion on which word was more appropriate in Bapu’s usage. That took more time than the actual dictation. In the end, the word that was kept was the one Bapu spoke—but only after Bapu conceded that the word Uncle had written was also correct.

On August 8, 1942, Bapu called on the British to “Quit India” and announced plans for a nationwide campaign of resistance. That same night, he, Uncle, and several others were arrested. They were imprisoned in the Aga Khan palace. Within six days, Uncle passed away.

Mother and I were denied permission to visit Bapu at this time. But it was granted later, when Bapu had begun a fast. A barbed wire fence, eleven feet high, had been set up around the entire palace. Seventy-six gunmen were on guard day and night. Bapu, weak from fasting, lay on a cot halfway along the palace’s long verandah.

We remained in the palace three weeks. We seldom talked to Bapu, for fear of straining him. But I had almost continual talks with Pyarelal, who had taken over as Bapu’s chief secretary. It was from these talks that I first discovered that Bapu did not approve of the sabotage of government property, as had become widespread in the absence of his leadership. I had been in favor of such actions. I too had planned to burn mailboxes on dark nights, in the company of a local gang armed with bamboo knives. I had made contacts with other gangs of saboteurs and had published underground bulletins. I believed that, short of destroying life or the property of individuals, there was no act that nonviolence ruled out.

Pyarelal patiently listened to all of this. But gradually he tried to show me how damage to any property was violent, how any secrecy hurt a nonviolent struggle. Violence was the government’s way, not ours. I slowly came to understand that the path I had favored was wrong.

At one point Bapu called me to him. He had heard I was reading a novel in English, and he wanted to compliment me on my command of the language. Pyarelal told him, “You still think of him as little Babla. But he discusses the national situation with me. We’ve been having an involved debate on nonviolence.”

I felt bashful. Bapu smiled and turned to me. “Since you were discussing nonviolence, you should know that my own idea of it has evolved. Earlier, I believed that if there was violence in one part of the country, it would not allow the use of nonviolence anywhere. Today I believe nonviolence must shed its small light in the midst of even the fiercest storm of violence.”

As I write these lines 1969 approaches, the centenary year of Bapu’s birth, and a quarter century since my father, Uncle, passed away. What is a quarter century, or a century, in the passage of eternity? Yet, even a moment’s encounter with the righteous—face to face, or in remembrances such as these—can be a boat that carries you across the sea of life.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is an excerpt from Narayan Desai’s childhood memoirs, Gandhi Through a Child’s Eyes, edited by and courtesy of Mark Shepard. For an audio interview with Desai and other material on nonviolence please consult Mark Shepard’s website.