Nonviolent Social Movements: The Street Spirit Interview with Stephen Zunes

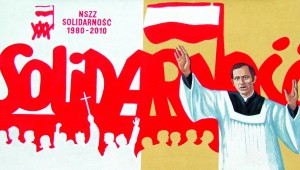

Polish mural commemorating 30 years of the Solidarity Movement; Father Jerzy Popieluszko foreground; artist unknown.

“In Bolivia in 1979, when there was a coup by a general named Natusch Busch, the whole country went on strike and 600,000 people massed in the Bolivian capital of La Paz, which was bigger than the total population of the city at the time. Trade union leaders and others walked into the president’s house, walked into his office, and they asked him, “What’s your program?” He looked at them, and then he looked at the 600,000 people out in the streets, and he said, ‘Yours!’” Stephen Zunes

Street Spirit: In your book, Nonviolent Social Movements: A Geographical Perspective, you and your co-authors described how nonviolent movements all over the world have undermined powerful systems of oppression through the mass withdrawal of cooperation. How can such a seemingly passive act as non-cooperation overcome a military dictatorship?

Stephen Zunes: Well, basically, for the state to operate, it needs people to carry out its orders — ranging from the security forces, to government bureaucrats, to sympathetic people in the media, to academics, and to many other people that may, in normal times, do the duty of the state, but can be convinced to be on the side of the people.

This is striking. I was in Bolivia a few years ago where they have had a long history of nonviolent resistance against right-wing dictatorships and neo-liberalism and all sorts of injustices. And it was amazing when I talked to everyone from illiterate peasants, to intellectuals, to people in the government, to urban workers — they’ll all tell you that the most powerful person in Bolivia is not the president or any elected officials, but the head of the trade union federation. Why? Because the unions can shut down the entire country.

So if there’s a general strike or other forms of mass resistance, it doesn’t matter if the government occupies various government offices, and has a monopoly of weapons, or, in some cases, a monopoly of media. If people refuse to obey their orders, then they don’t have any power.

Spirit: Yet a military regime still has the power to slaughter its nonviolent opponents, and throughout history, many have done just that. Even if a movement can erode support for an unjust regime, doesn’t it still have the power of violent repression?

Zunes: Well, the people in power — the elites — have this remarkably naive view of their own power. They assume that people love them and they have a bunch of yes men around them, and this is why they have a tendency to overreach.

I’ll just give you one example, from the Philippines. The dictator Ferdinand Marcos tried to steal the presidential election in 1986 by claiming that he won, when the opposition candidate, Cory Aquino, was the clear winner. Marcos was getting prepared for his inauguration, but at the same time, a massive rally was held to inaugurate Cory Aquino. And the question was which person would be recognized as the legitimate president — and it was very clear that it was Cory Aquino.

What’s interesting about the Philippines is that the people didn’t have to storm Malacañang Palace to overthrow Marcos. Instead, Marcos found out that Malacañang Palace was now the only part of the Philippines he still had any control over.

So we keep hearing stories saying, “Oh, nonviolence wouldn’t work in countries like Libya and Syria because these dictators are so brutal and they order their troops to kill innocent nonviolent protesters.”

But Marcos ordered his troops to murder nonviolent protesters in the Philippines. Erich Honecker, the last Communist leader of East Germany, ordered his troops to massacre nonviolent protesters. Repeatedly in history, we’ve seen dictators ordering troops to massacre unarmed protesters. Recently, Ben Ali in Tunisia ordered his troops to massacre protesters. But the military said, “No, we’re not going to do this.”

So it’s not a matter of how ruthless a dictator is. It comes down to whether the soldiers and others are willing to obey illegitimate orders.

Spirit: Does your research show that nonviolent movements historically are more effective than armed movements in eroding public support for unjust regimes?

Zunes: Very, very much so. Violent movements tend to get people to rally in support of the authorities, because violence turns people off. Now, it depends on the context. In some countries, the threshold is lethal force. In other countries, like the United States, even minor property damage can turn people off. But the fact is, you’ve got to think about what tactics you can use that are going to “grow” the movement. What kind of tactics are going to get people to see us as more legitimate than our opponents? It comes down to thinking strategically.

Spirit: Recent studies have shown that nonviolent uprisings can facilitate far broader popular participation in a movement. Have you found that to be the case?

Zunes: Yes. Armed struggle traditionally has been the province of young, able-bodied men who have access to weapons. Nonviolent struggles can involve everybody, pretty much. One of the key variables in determining the success of a movement is the level of participation. Many people who are willing and able to engage in nonviolent protest are not willing and able to engage in armed struggle. While certainly nonviolent protesters can get shot and killed, historically they’re far less likely to do so than if they’re being violent. So that is also something that makes people more likely to participate. The state pretty much has the advantage at every turn when it comes to the tools of violence, like guns. Where the state is most vulnerable is this idea of withdrawing cooperation. Nonviolent struggle is the ultimate asymmetrical warfare.

Spirit: What do you mean by asymmetrical warfare?

Zunes: It’s like jiu-jitsu or like Aikido, in that you can use the weight of the state, the force of the state, against it. That’s why some of the martial arts teach that when someone much bigger and stronger is attacking you, you don’t attack them in the same way. You use their own force and energy in such a way that you can disarm them. That’s exactly how nonviolent tactics work. Instead of going up against the state where they’re strongest, you simply change the rules. You use the tactics that give you the advantage.

The other thing is that maybe you don’t always want to focus on massive street demonstrations. This is particularly important if it is a situation where the regime can get away with killing people in large numbers. In that case, maybe you need to use tactics such as a general strike, stay-at-home actions, or boycotts — things that can weaken the state that people can get involved in without as much personal risk.

It’s just like in a guerilla movement — you don’t have a frontal assault on the capital first thing. A guerilla movement does low-risk, hit-and-run operations, builds the base in peripheral areas and gradually builds up from there.

Similarly, in a nonviolent struggle, you can’t expect to suddenly have hundreds of thousands of people in the streets that can force a regime to fall. It may seem that way sometimes, because often the news media doesn’t get to a country until it gets to that point. What we saw in Egypt, what we saw in Serbia, what we saw in the Philippines, what we saw in Poland, what we’ve seen in other cases of successful unarmed insurrections, was the culmination of many years of struggle.

Spirit: In her book, Why Civil Resistance Works, Erica Chenoweth found that when nonviolent movements are successful, they tend to create more democratic societies, with a greater commitment to human rights, than armed uprisings do. Do her findings resonate with your research?

Zunes: Oh, very much so. Again, it’s pretty logical when you think about it, because armed struggles traditionally are characterized by martial values, the ethos of an elite vanguard, a clear military hierarchy, and using force to get your way. That kind of model is one that tends to lead towards authoritarianism, where guerilla fighters take on the same kind of leadership style once they assume the reins of government.

By contrast, a successful nonviolent movement requires building diverse coalitions throughout civil society. That requires compromise. It requires a more pluralistic model in terms of organizational development as you build this coalition and bring people in and decide on your strategy and tactics. That can serve as the basis for more democratic institutions.

So instead of the message that power comes through the barrel of a gun, which encourages a more authoritarian model, we have the message of nonviolent movements, which encourage building alliances and getting as many people as possible involved in the process of change.

Spirit: So rather than power coming from the barrel of a gun in the form of military power, power comes from the people; people power?

Zunes: Exactly.

Spirit: You have written extensively about the conflicts in the Middle East. What would you say were the key factors that enabled the nonviolent uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt to grow so quickly and spread so widely?

Zunes: I think a key was that people were pretty clear that they did not accept this view that the fate of the Middle East was simply between al-Qaeda and other reactionary Islamic forces on the one extreme, and the United States and the neoconservative push for U.S. empire and domination, on the other.

They realized that, as opposed to what al-Qaeda said, they could overthrow these U.S. backed dictatorships nonviolently, and, unlike what the United States said, they could do it themselves, and they didn’t need foreign interference to do it.

Even though the transition to democracy in Tunisia and Egypt has been a bit rockier than some people had hoped, the fact is that you have this new generation that has been empowered, and now recognizes that they are the masters of their own fate. The traditional kind of fatalistic view was that their corrupt leaders or the foreign imperialist powers would forever impact what happens on the so-called Arab street. Instead, the Arab street has shown its ability to impact what happens to foreign powers.

It’s amazing, in the cases of Tunisia and Egypt, how the United States was defending those regimes in the early days of these rebellions, and as the movement grew, the U.S. called for reforms within the regime. And as the movement grew more, the U.S. started talking about the transition to democracy, and finally as the pro-democracy forces threw out the dictators, the U.S. ended up praising the movement.

Spirit: It seemed almost unbelievable that so many people could find the courage to confront such heavily armed regimes in Egypt and Tunisia. How do you think the common people found such an extraordinary level of courage?

Zunes: First of all, I think it showed how the vast majority of people in these countries did not consider those U.S.-backed dictatorships as legitimate. I think they realized that they could not work for reform within the system, but at the same time, that armed struggle was unworkable.

And they recognized that if you could get a certain critical mass of people out on the streets who were willing to defy the curfews and defy orders to disperse, it would demonstrate the impotence of a regime that people used to be just totally scared of and intimidated by.

So people were empowered by seeing those who were willing to face down the tanks and confront them with their bare hands and show that they’re not afraid. And when you did have those kinds of numbers, it was virtually impossible for even a well-armed government, even one with the support of the world’s one remaining superpower, to stop them.

Spirit: Courage seems to become contagious at key moments in a movement. Is the courage of the people an important component of nonviolent struggle?

Zunes: Yes, very much so. In some ways, this was a continuation of what we had seen from the Philippines to Czechoslovakia, and from Chile to Serbia. There have been scores of these kinds of uprisings. In fact, I was one of the few people who did predict that Egypt would likely have this kind of uprising because I had seen in Egypt over the previous years, a dramatic growth of civil society and a growth of nonviolent organizing by people who had a real interest in the power of strategic nonviolent action.

And while this is not news to me, I think it is news for a lot of people that Arabs and Muslims don’t like living under dictatorships any more than Christians in the West do. The form a democracy may take will inevitably vary according to a country’s unique history and culture, but the desire for freedom is universal. The desire for social justice is universal. And the recognition that strategic nonviolent action is the most effective way of moving in that direction is becoming increasingly universal as well.

Spirit: There were so many hopes engendered around the world by the Arab Spring. In its aftermath, how successful do you think these rebellions were in transforming these nations?

Zunes: Egypt’s situation is complex in that the younger and more politically progressive and more secular elements that led the revolution against Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak did not have the kind of experience and resources that some of the more conservative religious opponents of the old regime had.

So those elements, working in collusion at times with elements of the military, have succeeded in consolidating some degree of political power and continue to engage in human rights abuses. And the commitment of the Muslim Brotherhood to a more democratic future is certainly questionable.

However, the fact is that despite all the problems, there’s a lot more freedom than there was under Mubarak — more freedom both in terms of organizing and in terms of the media. And, more importantly, people have been empowered. People are not afraid to go out in the streets and confront those in authority.

I remember being in a café in Cairo recently and watching the TV news. The TV news in Egypt used to always be the president giving a speech, or the president meeting a visiting foreign dignitary — and that’s what the news was. But this evening, the news was about a labor strike in Alexandria. It was about the relatives of the martyrs of the revolution having a vigil in front of the Interior Ministry. It was about the revolution going on in Syria. All the news was about ordinary people engaged in acts of resistance. I think that, more than anything, shows how Egypt and the Middle East are changing. Who are the newsmakers? It’s ordinary people who are struggling for change. It’s not just the men in suits.

Spirit: That’s a beautiful legacy. The grass-roots resistance during the Arab Spring reminded me of the earlier insurrection in the Philippines, where “people power” overthrew a dictatorship.

Zunes: When the U.S. backed dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, brazenly stole an election in 1986, you had widespread protests, boycotts of crony industries associated with his regime, and dissent was brewing.

A couple of reformist military officers tried to stage a coup against Marcos, but they were cut short and the small base near the capital where they had set up their resistance was about to be overrun by elements of the military still loyal to the dictator. At that point, hundreds of thousands of people surrounded the base and protected the reformist officers.

Despite orders by Marcos for the soldiers to shoot their way in, they refused. You had nuns praying the rosary in front of the tanks. You had ordinary people giving flowers and treats to the soldiers, trying to talk to and communicate with them, trying to get them on the side of the people. Eventually, it got to the point where there was massive non-cooperation throughout the country, and it was clear that the gig was up and Marcos had to flee.

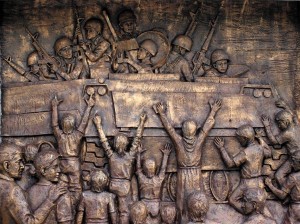

Unarmed citizens confront tanks and troops; statue commemorating the People Power revolution in the Philippines; artist unknown.

This was during the Reagan administration, and the United States was initially supporting Marcos, but with the news media showing the extent of the opposition and their democratic, nonviolent nature, it became almost impossible for the United States to get away with continuing their support for the dictatorship.

It was so inspiring to see that kind of nonviolent resistance on people’s TV sets at night. When people would see that kind of courage and nonviolence in the face of repression, it forced them to pick sides and to choose the nonviolent, pro-democracy, pro-justice side.

Spirit: The People Power movement in the Philippines was inspiring for people everywhere in the world. Didn’t it come not long after Poland’s Solidarity movement, another enormously powerful example of nonviolence in action?

Zunes: Poland was interesting because they were very smart strategically. In China, in 1989, the pro-democracy students all amassed in the heart of Beijing, in the heart of the Communist Party’s political power, and demanded the whole system be changed. And, of course, they were massacred.

In Poland, by contrast, though they had that same kind of goal — to bring down the Communist system — they were strategic enough to start small. They began by simply occupying the shipyards in a port city and demanding recognition of an independent trade union, along with a few specific concerns regarding the reinstatement of fired union activists.

But by having that, they could then grow the movement. Solidarity started getting members not just from other shipyards, but also from factories, mines and workplaces all over the country. They had intellectuals, farmers, and even government workers signing on. They gradually increased their demands — again, not calling for the downfall of the whole system, but pushing for greater democracy and fairness and justice.

The original Solidarity strikes began in the summer of 1980, and martial law was declared a year and a half later, in December of 1981. By the time the government cracked down, the movement was strong enough that it could survive underground and eventually bring down the entire system.

What they recognized was, just like in any other struggle, you can’t expect to have an immediate victory. You need to engage in a whole sequence of different tactics. You need to have small victories to show you can win and get more people on your side. As you get stronger, you can start demanding more. In other words, you’ve got to think strategically. You’ve got to think and plan for the long-term. The Polish Solidarity movement was particularly effective in that way.

Spirit: Despite these historical examples, many people still can’t understand that a nonviolent movement can overthrow a military dictatorship.

Zunes: In Bolivia in 1979, when there was a coup by a general named Natusch Busch, the whole country went on strike and 600,000 people massed in the Bolivian capital of La Paz, which was bigger than the total population of the city at the time. Trade union leaders and others walked into the president’s house, walked into his office, and they asked him, “What’s your program?” He looked at them, and then he looked at the 600,000 people out in the streets, and he said, “Yours!”

Well, to their credit, they didn’t insist that he adopt their program. They insisted that he step down, and democratic government was restored. I think that’s illustrative of this very important point: that if people refuse to cooperate, you don’t have power. That dictatorship lasted less than two weeks.

Spirit: But it often doesn’t go down that quickly and without bloodshed. It is hard for some to even comprehend why any people would continue on the path of nonviolent resistance in countries when they are massacred by the military.

Zunes: Well, an interesting case actually occurred in Mali. Until the military coup in March of last year, Mali had one of the longest running democracies in West Africa. Back in 1991, 20 years before the Arab Spring, they had a nonviolent uprising in Mali.

Even though the soldiers ended up gunning down literally hundreds of nonviolent protesters, people kept on coming until the military just threw down their arms and refused to fire anymore. The dictator, General Moussa Traoré, was removed from power and replaced with a civilian democratic government.

Now, what was interesting is that back then in Mali, they of course didn’t have the Internet or Facebook, and a large part of the population at that time was illiterate. They spread the word using griots, the traditional singing storytellers. They used these allegorical tales of resistance going back for centuries.

It’s an indication that you don’t need modern social media to organize. When people feel the need to communicate, they will communicate. People can figure out how to rely on their own unique cultural and historical resources to mobilize. And, despite severe repression, if people persist, they can win.

Spirit: Another dictator who was willing to use violent repression against unarmed demonstrators was the Shah of Iran. His regime was heavily armed and directly supported by the U.S. government, so how did a nonviolent uprising by the Iranian people ever turn the tide?

Zunes: There was a story I really liked in the uprising against the Shah of Iran. The Shah was a brutal, U.S. backed dictator, and he was kind of a megalomaniac. He put up statues of himself in almost every town in the country. So it was popular during this period for people to tear down the statues. So when soldiers would come into a particular area, the first thing they would do would be to surround the statue to protect it.

There was this one Iranian town where, instead of attacking the soldiers and creating a riot, the people came and talked to the soldiers and shared their grievances about the Shah. They brought the soldiers food, and they brought them blankets because it got cold at night after the curfew, and the soldiers had to stay out there.

They did this for a couple days and then one morning, when people came out after the lifting of the curfew at dawn, they found the soldiers gone and, before they had left, the soldiers themselves had torn down the statue!

Spirit: The soldiers themselves tore down the statue of the Shah? That’s amazing! What lesson do you draw from this?

Zunes: It’s an illustration, I think, of recognizing that even people in the security forces can be your allies, and they’re more likely to be won over if you’re nonviolent to them than if you’re trying to attack them.

Spirit: Do you think that people around the world are becoming more aware of the power of nonviolent resistance to overcome tyrannical regimes?

Zunes: Nepal is an interesting case, because in Nepal you had a long-running, armed struggle against the monarchy by Maoist guerrillas. They recognized that they could end up controlling some parts of the countryside, but they really did not have the means of bringing down the monarchy. It had been around for hundreds of years and it had a strong military.

So what they decided to do was to lay down their arms and join in an alliance with liberal democratic opponents of the regime. They ended up having a nonviolent revolution that overthrew the monarchy. So, after hundreds of years, Nepal is now a republic and able to have democratic elections. It shows that even Maoist guerillas can recognize that nonviolent action can actually be more powerful than guerilla warfare.

Spirit: In the analysis of many people, it was the threat of prolonged armed struggle by the African National Congress (ANC), along with the international boycotts, that enabled the people of South Africa to end apartheid. What role, if any, did nonviolent organizing play in overcoming apartheid?

Zunes: Nonviolent action in South Africa was far, far more significant than the fairly limited efforts by the armed wing of the resistance. The ANC never formally renounced armed struggle, but they recognized long before the downfall of apartheid that it would be civil resistance that would be the most decisive factor in bringing majority rule to South Africa.

Spirit: What forms of civil resistance were organized in South Africa?

Zunes: In the case of South Africa, we’re talking about strikes, which were particularly significant since the white minority regime was totally dependent on black labor. Boycotts helped turn the business community against the system, combined with international sanctions, which were made possible by nonviolent resistance in the United States and other countries and helped to halt foreign investment in the country.

Also important were the creation of alternative institutions such as parallel government in the townships and elsewhere, as well as demonstrations, civil disobedience and other methods of resistance.

The armed wing of the ANC was only one small component of the ANC. Their political wing within South Africa was allied with the United Democratic Front, and COSATU, the Congress of South African Trade Unions. They organized these massive nonviolent resistance campaigns, and despite severe repression and despite efforts to sow divisions within the black movement by the regime, it was the nonviolent component that was the most critical in overcoming apartheid. And indeed, I have talked to a number of former ANC activists who have acknowledged this themselves.

Spirit: Back during the anti-apartheid movement in the United States in the 1980s, did you think nonviolent resistance would end up playing such a crucial role in liberating South Africa?

Zunes: Everything from the geography of the nation, to the absence of sanctuary, to the South African security apparatus, made a military victory by the armed wing of the ANC impossible. During this period, I was very active in the divestment campaign and the anti-apartheid movement in this country. I was an organizer in this movement when I was an undergraduate at Oberlin College, and later at Cornell as a grad student.

While I could never make a moral judgment against the black South Africans who felt the need to take up arms, I wanted the people of South Africa to win, and I believed that nonviolent struggle was clearly the most effective means. The South Africans themselves were recognizing that unarmed civil resistance would be the most effective way of overcoming apartheid.

F.W. de Klerk, the last white president of South Africa, who negotiated the deal to end apartheid, acknowledged that the government was all ready to challenge any military threat. It was the nonviolent resistance that forced them to negotiate with the ANC and release Mandela. [F.W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 for their role in negotiating an end to apartheid. TM]

Spirit: How did nonviolent resistance force the South African regime to negotiate with the ANC?

Zunes: Basically, the country was becoming ungovernable due to the nonviolent resistance in South Africa — when combined with the international sanctions which were destroying the economy.

Spirit: And didn’t those international sanctions come about because of the widespread nonviolent resistance of groups in the United States and Europe?

Zunes: The United States and other countries were very reluctant to impose sanctions because investment in South Africa was very profitable to very powerful corporations. This U.S. policy was reversed because of the mass nonviolent movements led by church groups, labor unions, student groups and international organizations and others.

Spirit: Your book, Nonviolent Social Movements: A Geographical Perspective, seems to focus almost exclusively on analyzing cases where nonviolent movements aren’t simply going after piecemeal reforms, but are trying to topple brutal military regimes.

Zunes: Yes, I am referring to insurrections against autocratic regimes, as opposed to reform movements within various countries.

One of the key variables determining whether they’re going to be successful or not is the defections from the police, military and other security forces. People in these security forces are far more likely to disobey orders to fire into crowds of nonviolent protesters than they are with orders to fire on people who are shooting at them.

Another factor is that in any movement, even against a dictator, there are lots of people who either might support the regime, or may feel that even if they don’t like the current regime, they’re afraid of what the successful revolution might bring.

Spirit: They’re afraid a revolution might bring a new kind of repression?

Zunes: Yes, or chaos or other problems. So people are far more likely to join the movement if it’s nonviolent. A nonviolent movement is seen as a lot less threatening and more likely to lead to responsible governance than an armed group.

Violence can alienate a movement’s potential supporters, and the regime can use that violence as an excuse to depict the opposition as terrorists. People will be more open to accepting repressive actions by the state if it’s seen as necessary to combat a violent opposition. Repression is much less likely to be accepted if it’s against a nonviolent opponent.

Spirit: Even in a faceless regime with its seemingly faceless security apparatus, there are still individual soldiers who may be unwilling to shoot into a defenseless group of civilians. So do nonviolent movements succeed, in part, because they appeal to the individual conscience — even in a dictatorship?

Zunes: Yes, and one need not convert the people at the top. You merely need to make it impossible for them to continue to govern. At the same time, to make that possible, it helps to appeal to the consciences of the ordinary folks — ranging from police and soldiers to government bureaucrats to workers in key industries — to end their cooperation with the state. And a movement can do that by appealing to their moral sensibilities.

Spirit: The government and the state-controlled media often try to deceive the public by painting a movement as destructive and extremist. How can activists counter the disinformation of the state?

Zunes: The people in power will try to depict their opponents in the most negative light possible. They will depict them as being agents of foreign governments or terrorists or people who embrace extremist ideologies or outside agitators — all sorts of things. So it’s important for the opposition to engage in the kinds of tactics that would challenge these stereotypes and expose the lies of those in power.

What’s exciting about this nowadays is that a lot of people have smart phones and the ability to film or photograph what’s actually going on out in the streets, and can immediately post it out for everyone to see. It’s much harder now for the police and government officials to misrepresent confrontations. In other words, it’s not just for the people who witness a particular confrontation in person, but it can get out around the world — literally.

Spirit: Gandhi’s vision of nonviolence included the Constructive Program — the creation of independent institutions and economic programs. That aspect of nonviolent struggle is often neglected in the U.S. What kind of parallel institutions are important in successful movements?

Zunes: In places like the United States, it can mean everything from a food co-op to a battered women’s shelter and other alternatives to the status quo, with individuals taking on certain ways of meeting the needs of the people that help empower people.

In insurrectionary situations, you can actually have independent structures of governance. For example, in South Africa, the leadership of the black townships that had been appointed by the white minority rulers was ignored, and in some cases, physically driven out of the buildings. In their place, the resistance built up parallel governance and elections, and the people started governing themselves. They built their own parallel judicial system and a parallel system of distributing services and goods.

It showed the world, “Hey, black people can govern themselves, and we can do it more fairly and democratically than the white minority regime.”

Whether they are in a place like the United States or in South Africa or in the Palestinian territories, or other places where we’ve seen this happening, developing these alternative institutions have actually empowered a lot of people. They’ve been empowered by training in some very practical skills that can be useful after the revolution when they govern themselves.

But perhaps even more importantly, whatever kind of government comes forth, people will have become experienced leaders in the process — people who had previously felt disempowered. This is particularly true for people who have been subjected to racism and sexism and other forms of oppression, and who are given the message, “You’ve got to trust the State because you’re not smart enough. You don’t have the skills to take care of yourselves and your community.”

When people finally can do that for themselves, they’re empowered. This empowerment enables them to not just develop stronger, more effective alternative institutions, but can also empower them to be more active in challenging the status quo and working for change for everybody.

Spirit: Let’s look at a recent example of a nonviolent uprising in the United States. Did you take part in the Occupy demonstrations in 2011 and 2012?

Zunes: Yes, not on a daily basis, but I did join folks in both San Francisco and Oakland on Occupy marches.

Spirit: What do you think was meaningful about the Occupy movement? What lessons can be learned from it?

Zunes: Well, the good news, I think, is that Occupy changed the debate in this nation. The gross inequality in this country and the plight of the poor is now considered legitimate political discourse, and is now part of the mainstream. We don’t have nearly the progress we should have, of course, but at least people are talking about economic inequality and poverty and the concentration of wealth. I think that’s really important.

I think the main problem was that there wasn’t broader strategic thinking in terms of the next steps. The Occupy encampments were an important piece, but there needs to be a plethora of other kinds of tactics, including the kind of door-to-door organizing which may not be as exciting for some people as a demonstration or a takeover of a certain piece of territory. But it’s very important to bring in a diverse cross-section of the population. If you really are representing the 99 percent, you want to broaden the base of support.

Spirit: What kinds of door-to-door organizing could have been done?

Zunes: I think a lot of this has to do with political education. It means listening to a lot of people and seeing what their grievances are. Because I think you’ll find that a lot of people have a lot of grievances about their lives, and the movement will find that these grievances are rooted in some of the same structural problems that are related to other people’s grievances. And basically, in finding out what people’s concerns are, you will find what they might get involved in, and see how you might be able to bring them in, and plug them into the movement.

Spirit: Also, it seems that a movement that actually listens to the people is a good example of the kind of government that could arise, one that would listen to its own people and be responsive?

Zunes: Exactly, exactly. Yes.

Spirit: Do you think the sporadic acts of street violence helped to shorten the life-span of the Occupy movement?

Zunes: I think that the scattered violence — although it was primarily against property, and it was only a minority of people, and it was not all that significant — did end up turning off a lot of people to the movement as a whole. Whenever you have a movement that uses mixed tactics, the media will always concentrate on the most violent element, and will try to portray the whole movement as the most violent element.

We saw it that day (Nov. 2, 2011) when 10,000 people shut down the Port of Oakland nonviolently with the support of the longshoremen’s union. That was one of the most remarkable events of the entire Occupy movement in the entire country. But the media coverage the following day was primarily of a handful of self-described anarchists smashing windows in downtown Oakland later that evening.

There was not a really concerted effort, as much as there should have been, to try to separate the movement from the handful of people who were engaged in irresponsible tactics, and to marginalize those kinds of narcissistic elements who were more interested in exercising their own selfish, cathartic expressions of rage, than advancing the movement as a whole.

You find that police forces will traditionally use agents provocateurs, that is, government agents who will pose as protesters and do something violent or provocative as a means of enabling the police to crack down even harder and discredit the movement as a whole. So it seems quite logical that you do not want to do what the authorities want you to do — by being violent.

Spirit: During the Occupy actions, you wrote that there was an inability — nearly a refusal — to state clearly what the demands of this movement were and to formulate strategies and tactics that could advance those demands. What could this movement have done in that area?

Zunes: While maintaining a fairly long-range vision of more radical change, it also could have had more specific, targeted campaigns that a lot of people from a wide variety of orientations might have been able to identify with and get behind, such as ending foreclosures.

It’s important for even the most radical movement to have more immediate, short-term campaigns on specific goals that are winnable and which people would be willing to support and be part of — even those who may not necessarily share the long-term vision.

Spirit: You also wrote that the Occupy protests were very inspiring, but added that “being right isn’t enough, especially when you’re up against the powers of Wall Street.” Beyond being right, what else did this movement need in order to challenge the powers of Wall Street?

Zunes: I think the movement needed to build more alliances with working people, and with people of color, and with others who have been negatively affected by the growing concentration of corporate wealth. Also, it needed to channel this energy into specific campaigns with more immediate, achievable goals — and make the movement an environment where people would enjoy taking part, where they felt safe, where they could bring their kids, and where there could be something that people would be inclined to get involved with and want to come back for more.

Spirit: Why do you think the Occupy movement has seemingly faded away so quickly, when just last year it seemed to hold such great promise?

Zunes: I think part of it was that when they started just using the same basic tactics over and over again, people got bored, people got tired. You need to keep it fresh, and there are times when you also need to make tactical withdrawals and then reappear in different ways, with a new focus on specific campaigns that will spark new interest.

Spirit: Whatever its problems, Occupy was one of the most massive outpourings of popular dissent against economic inequality in our lifetime. Did its rapid emergence surprise you?

Zunes: I certainly didn’t expect it, but in hindsight, I can very much see how it happened. The vast majority of people in this country are feeling in their daily lives the negative consequences of the economic and political trends in this country that people in Occupy were protesting about. So it immediately had resonance for folks. People could identify with those demands. The fact that conventional politics was not addressing it made the movement particularly attractive, so it came at just the right time.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Stephen Zunes is Professor of Politics and International Studies at the University of San Francisco, and chair of the university’s Middle Eastern Studies Program. He serves as a senior policy analyst for the Foreign Policy in Focus project of the Institute for Policy Studies, is an associate editor of Peace Review, a contributing editor of Tikkun, and chair of the academic advisory committee for the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. Among his many titles are:

- ZUNES, S. & J. MUNDY. Western Sahara: War, Nationalism and Conflict Irresolution, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2010.

- ZUNES, S. & R. MCNAIR (eds.) Consistently Opposing Killing: From Abortion to Assisted Suicide, the Death Penalty, and War. Westport, CT.: Praeger Press, 2008.

- ZUNES, Stephen. Tinderbox: U.S. Foreign Policy and the Roots of Terrorism, Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press, 2002.

- ZUNES, S., L. KURTZ & S. ASHER (eds.) Nonviolent Social Movements: A Geographical Perspective. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing, 1999.

Please consult Stephen Zunes’s website for further information.

Terry Messman is the editor and designer of Street Spirit, a street newspaper published by the American Friends Service Committee and sold by homeless vendors in Berkeley, Oakland, and Santa Cruz, California; he is also editor of the website with the same name. He has been for the past 13 years the program coordinator for the AFSC’s Homeless Organizing Project. We are grateful to Terry Messman and Street Spirit for permission to post this interview.