Kasturba Gandhi and Women Satyagrahi in South Africa

by E. S. Reddy

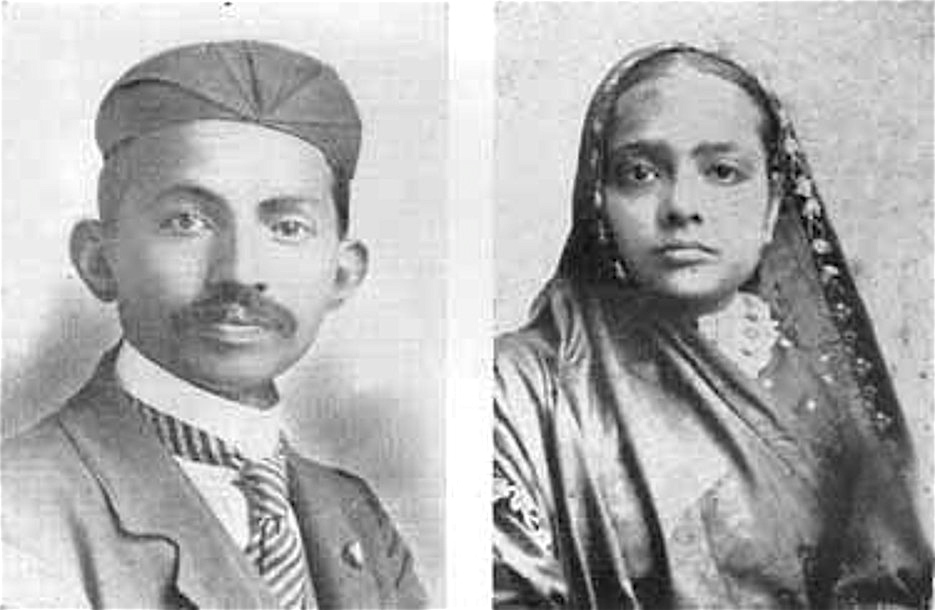

Portraits of Mohandas and Kasturba Gandhi at the time of the South African campaign; courtesy en.wikipedia.org

Editor’s Preface: We have posted several articles on significant figures in the Satyagraha movement, other than Mahatma Gandhi. We have also featured articles on women nonviolence leaders such as Vandana Shiva and Dorothy Day. This article concentrates on the role Gandhi’s wife, Kasturba Gandhi (1869–1944), played in the South African satyagraha campaign. Please also see the note at the end for biographical information about the author, and acknowledgments. JG

Kasturba Gandhi by her “silent suffering” as a prisoner sentenced in 1913 to three months rigorous imprisonment, made a crucial contribution to the success of the nonviolence civil resistance campaign (satyagraha) in South Africa, but this is little known.

In early 1913, when satyagraha in the Transvaal had been suspended, Justice Malcolm Searle of the Cape Supreme Court ruled that marriages performed according to a religion which allowed polygamy – that is, all Muslim and Hindu marriages – would not be recognised in South Africa. If this ruling had prevailed, almost all married Indian women would have been reduced legally to the status of concubines and their children treated as illegitimate. The women and children would have lost the right of inheritance and the right to enter South Africa. The government ignored repeated appeals from the community for legislation to remedy the situation.

Gandhi consulted his associates in the Transvaal about renewing the satyagraha with two principal demands: recognition of the status of Indian marriages and the abolition of an onerous tax of three pounds imposed on former indentured labourers, their wives and children to force them to re-register their indenture or leave South Africa. They agreed that women should be invited to join the satyagraha as the honour of Indian womanhood was involved.

In the Transvaal many wives of satyagrahis volunteered for their own campaign. They had been for years eager to join their husbands in resistance and share the suffering for the honour of India. It was decided that they would court arrest by hawking their wares on the street without permit and, if they were not arrested, go to Newcastle in Natal to persuade the mineworkers to strike.

Gandhi then went to Phoenix ashram and spoke to the community. Kasturba, his wife, was the first to volunteer, despite her poor health. (1) Indian Opinion (1 October 1913) reported:

The ladies [in Phoenix] were allowed to join the struggle after great effort was made by them to take part in it. When Mrs. Gandhi understood the marriage difficulty, she was incensed and said to Mr. Gandhi: ‘Then I am not your wife, according to the laws of this country.’ Mr. Gandhi replied that that was so and added that their children were not their heirs. ‘Then,’ she said, ‘let us go to India.’ Mr. Gandhi replied that that would be cowardly and that it would not solve the difficulty. ‘Could I not, then, join the struggle and be imprisoned myself?’ Mr. Gandhi told her that she could but that it was not a small matter. Her health was not good; she had not known that type of hardship and it would be disgraceful if, after her joining the struggle, she weakened. But Mrs. Gandhi was not to be moved. The other ladies, so closely related and living on the Settlement, would not be gainsaid. They insisted that, apart from their own convictions, just as strong as Mrs. Gandhi’s, they could not possibly remain out and allow Mrs. Gandhi to go to jail.

The first batch of satyagrahis – twelve men and four women – went from Phoenix to the Transvaal border on 15 September 1913; they were arrested for crossing the provincial border without permits. Three of the women – Mrs. Kasturba Gandhi, Mrs. Chhaganlal Gandhi and Mrs. Maganlal Gandhi – were from the Gandhi family and the fourth, Ms. Jayakunwar Mehta, was the daughter of Pranjivan Mehta, a friend of Gandhi in London. They were sentenced on 23 September to three months with hard labour.

Twelve women, with six babies in arms, crossed the border from the Transvaal to Free State at the end of the month and were not arrested. They returned to Vereeniging in the Transvaal and hawked their goods without permits, but were again not arrested. They then proceeded to Newcastle in Natal according to plan. Thambi Naidoo, the veteran satyagrahi, led them on their mission to persuade workers to strike. The twelve women included the wife and mother-in law of Thambi Naidoo and the sister-in law of Mrs. Thambi Naidoo. All of them were Tamils, except for Mrs. Bhawani Dayal.

Thambi Naidoo took them around the railway barracks and the coalmines to exhort the Indian workers to strike. He addressed thousands of people at meetings in the coal-mining area. The strike was in full swing when Gandhi rushed to Newcastle on 20 October. “The appearance of the brave ladies simply acts like a charm and the men obey the advice given them without any great argument being required,” reported Indian Opinion on 22 October. The workers had already heard of the imprisonment of Kasturba and other members of the Gandhi family. The strike spread like wildfire after Gandhi arrived.

The Transvaal women were charged on 21 October under the Vagrancy Act. They admitted that they had come to Newcastle to advise the mineworkers to suspend work until the government promised to repeal the three pound tax. They were sentenced on the same day to three months with hard labour, and taken to the jail in Maritzburg where the Phoenix women were incarcerated. A second batch of women – including Valliamma, the teenage heroine of the satyagraha – followed early in December. They too were sentenced to three months rigorous imprisonment.

The brutal treatment of the striking workers and the harsh sentences on the women outraged public opinion in India. Sir Pherozeshah Mehta, “the lion of Bombay” who had not supported the satyagraha until then, roared after the arrest of the women that “his blood boiled at the thought of these women lying in jail herded with ordinary criminals, and India could not sleep over the matter any longer.” There were demands for an impartial investigation into the treatment of the striking workers and the satyagrahis. Lord Hardinge, the Viceroy, in an unusual move, publicly expressed his sympathy with the satyagrahis and conveyed to the South African and British Governments the strength of feeling in India.

To appease Britain and to divide the Indian community, the South African Government set up an Indian Grievances Commission on 11 December 1913. Sir William Solomon, a respected judge, was appointed Chairman. The two other members were Ewald Esselen and J.S. Wylie, two prominent advocates, who were both well known as anti-Indian. The Indian community, at meetings all over the country, protested against the composition of the Commission and called for the addition of two members acceptable to the Indians.

On the recommendation of the Commission, Gandhi was released from prison on 18 December [having been sentenced to nine months on 11 November]. He addressed mass meetings in Johannesburg and Durban, which decided on a boycott of the Commission unless it was expanded and all satyagrahis in prison released. It was agreed that if these requests were rejected, the Indian community would resume civil resistance with a march on 1 January (1914). Gandhi expected that 5,000 people would join the march and that their ranks might swell to 20,000. (2) General Smuts rejected the requests of the community.

Lord Ampthill from London and Gopal Krishna Gokhale from India strongly urged Gandhi not to boycott the Commission and to abandon the renewal of civil resistance. Gandhi informed them that the mass of the people were so indignant that if any attempt was made to advise acceptance of the present Commission, they would kill the leaders. Gokhale appreciated Gandhi’s position and, though ill, was almost in daily contact with Gandhi while pressing Lord Hardinge for appropriate action.

Gandhi was faced with a dilemma. The Indian community would resent abandoning the march, while proceeding with it would alienate sympathy in Britain and India, which he had cultivated over many years. Moreover, there was the likelihood of violence by Europeans and the government if resistance was resumed. (3)

In the midst of these events, Kasturba and her party of satyagrahis were released from prison on 22 December. The Indian community had planned a huge procession in Durban to welcome them. But that had to be abandoned as Kasturba came out emaciated.

Describing the heroism of the women satyagrahis, Gandhi wrote in his book, Satyagraha in South Africa:

The women’s bravery was beyond words. They were all kept in Maritzburg jail, where they were considerably harassed. Their food was of the worst quality and they were given laundry work as their task. No food was permitted to be given them from outside nearly till the end of their term. One sister was under a religious vow to restrict herself to a particular diet. After great difficulty the jail authorities allowed her that diet, but the food supplied was unfit for human consumption. The sister badly needed olive oil. She did not get it at first, and when she got it, it was old and rancid. She offered to get it at her own expense but was told that jail was no hotel, and she must take what food was given her. When this sister was released she was a mere skeleton and her life was saved only by a great effort.

The “sister” was obviously none other than Kasturba.

Gandhi had to deal with the critical stage of the satyagraha while nursing Kasturba who was hanging between life and death. On 27 December, he received two messages, which provided a solution for his dilemma. One was a message from Gokhale that Lord Hardinge was sending a senior civil servant, Sir Benjamin Robertson, to South Africa to assist the Indians and was asking the British Government to secure adjournment of the meetings of the Commission. The other was a surprise: a telegram from Miss Emily Hobhouse appealing to him as a “humble woman” to postpone the march for fifteen days.

Emily Hobhouse (1860–1926) had staunchly opposed the Second Boer War, and went to the concentration camps where Boer women and children were kept in such deplorable conditions that 27,000 women and children died. Her courageous campaign against the war, braving denunciation that she was a traitor, had much to do with the end of the war and the efforts at reconciliation between the British and the Boers. For Gandhi, who had been seeking support of persons with influence on the Boers, her message was a godsend. He wrote in Satyagraha in South Africa: “The Boers looked up to her with great respect and affection. She was very intimate with General Botha.”

According to Raojibhai Patel, Gandhi consulted his colleagues on the appeal of Miss Hobhouse and decided to postpone the march by fifteen days. Whether it was due to the appeal of Miss Hobhouse or the telegram from Gokhale or both, a crisis was averted. Gandhi was able to announce at a public meeting in Maritzburg on the same day that important negotiations were proceeding in connection with the grievances of the Indians and that the march might not take place until 15 January.

The papers of Miss Elizabeth Molteno in the archives of the University of Cape Town explain the intervention of Miss Hobhouse. (4) Miss Molteno, a member of one of the most prominent families in the Cape, had also opposed the Anglo-Boer War and went to live in London for several years. She became a friend of Emily Hobhouse and met Gandhi during his visit to London in 1909. Returning to South Africa, she bought a cottage in Ohlange, near Phoenix, and took a keen interest in the Indian struggle. She went to see Kasturba on her release and spent a long time with her enquiring about her health and the conditions in prison. She sent a message, through her friend Alice Greene, to Emily Hobhouse who had come to South Africa to attend the unveiling of a memorial to Boer women in Bloemfontein but had to remain in Cape Town because of illness.

This is how Alice Greene described the origin of the telegram to Gandhi:

She (Miss Hobhouse) was sitting up on her couch … I told her I had sent off a telegram to Gandhi and that you had suggested her sending one too. She instantly took pencil and paper and wrote down a long telegram which I sent off … She sent it to Maritzburg to catch him at the mass meeting that afternoon. It was to the effect that her personal sympathy was intense but that she would venture to advise patience. It would not do to alienate sympathy and even endanger the very cause itself. Could he not wait until the meeting of Parliament before having recourse to further resistance? Even yet English women had not achieved full freedom. She used much gentler language than this, but that was the gist of it. She told him also that everything was being followed with much sympathy and feeling.

When Gandhi agreed to the postponement of the march, Miss Hobhouse wrote a long letter to General Smuts recalling her special connection with India through her uncle. She said that as a woman without a vote, she sympathised with other disenfranchised folk as the Indians. She then pressed him to meet and talk to Gandhi:

You see January 15 (1914) is the date now proposed for another march. Before then some way should be found of giving private assurance to the leaders that satisfaction is coming to them. Their grievance is really moral … never will governmental physical force prevail against a great moral and spiritual upheaval. Wasted time and wasted energy.

General Smuts could not possibly ignore an appeal from her. On his invitation, Gandhi went to Pretoria on 9 January. C.F. Andrews, who accompanied Gandhi to Pretoria, wrote:

There can be no doubt that during the days that followed, the influence of Miss Hobhouse with the Boer leaders did much to pave the way to a reconciliation. While we were in Pretoria she wrote again and again both to Mr. Gandhi and myself. She thus kept herself in touch with the whole negotiations and took part in them. (5)

Gandhi was surprised to see a great change in the attitude of General Smuts. Negotiations were delayed by a railway strike but soon after it ended, a provisional agreement was reached quickly and signed on 22 January.

Gandhi and Kasturba went to Cape Town in mid-February to bid farewell to C.F. Andrews and to follow the developments on the Indian question. Kasturba’s condition deteriorated and gave cause for grave concern.

Miss Molteno and Miss Greene frequently visited the Gandhis at the home of Dr. A.H. Gool where they stayed and enquired about her health. Miss Molteno introduced Gandhi to many influential personalities. She arranged for the Gandhis to meet Miss Hobhouse who was staying at Groote Schuur, the residence of Prime Minister Louis Botha. There they met Mrs. Botha, as well as Mrs. Gladstone, wife of the Governor-General, who were both friendly and considerate.

Gandhi had written many times to General Botha for an interview but without success. But a few days after meeting the Gandhis, Miss Hobhouse invited Gandhi again for a discussion at Groote Schuur – and General and Mrs. Botha joined them. When the Indian Relief Bill came before Parliament it was reported that Prime Minister Botha threatened to resign if the Bill was not passed. (6) Why did he take the adoption of a bill to end injustices to a small, voteless and vulnerable community as a matter of vital importance? Was he thinking of Miss Hobhouse and the meeting with Gandhi which arose out of the “silent suffering” of Kasturba?

When Miss Hobhouse died, Gandhi wrote in an obituary in Young India on 15 July 1926: “She played no mean part at the settlement of 1914 … Let the women of India treasure the memory of this great Englishwoman.” Kasturba, whose “silent suffering” persuaded Miss Hobhouse to intervene, equally deserves the gratitude of the people of India and Indians in South Africa.

Endnotes:

(1) Gandhi made an error in Satyagraha in South Africa, written from memory in prison many years later, in stating that he had spoken to Kasturba after other women in Phoenix had agreed to court imprisonment. He wrote to Gokhale on 19 April 1913: “Mrs. Gandhi made the offer on her own initiative…” Raojibhai M. Patel, a resident of the Ashram and a member of the first batch of satyagrahis from Phoenix, was present during the conversation between Gandhi and Kasturba. He wrote in The Making of the Mahatma: Gandhiji ki Sadhana (Ahmedabad: Published by the author, 1990) that he had pointed out the error to Gandhi and that Gandhi agreed, after consulting Kasturba, to correct the text. Note also that the first English edition of Gandhi’s Satyagraha in South Africa was published in Madras (India) by Ganesan Publishers in 1928; Gandhi was the translator, from his original Gujarati.

(2) Gandhi, cable to Gokhale, 26 December 1913.

(3) C.F. Andrews, who had been sent by Gokhale to South Africa to assist the Indians, informed Gandhi that Europeans had told him: “If the Indians go out again, there will be shooting.” C. F. Andrews, “Mr. Gandhi and the Commission”, Modern Review, Calcutta, July 1914.

(4) Please see my article, “Some Remarkable European Women Who Helped Gandhiji” in E. S. Reddy, Gandhiji: Vision of a Free South Africa, New Delhi: Sanchar Publishing House, 1995.

(5) C.F. Andrews, “Mr. Gandhi at Phoenix”, Modern Review, Calcutta, May 1914.

(6) Gandhi said in a speech in Kimberley on 2 July 1914: “General Botha, it must be admitted, has done much for us, seeing that, for the sake of a community as docile as the Indians, he threatened to resign if the Bill was not passed.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Enuga Sreenivasulu Reddy (b. 1924) has held several positions at the United Nations. He was the driving force behind the Special Committee against Apartheid, for which he was Secretary (1963–1965) and was also the director of the Centre Against Apartheid (1976–1983). He has served as Director of the UN Trust Fund for South Africa, Director of the Educational and Training Programme for Southern Africa and was also Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations (1983 to 1985). Among his many works he is the author of Gandhiji: Vision of a Free South Africa. New Delhi: Sanchar Publishing House, 1995. This article has been shared with mkgandhi.org, under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.