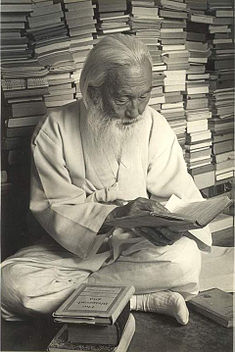

The Legacy of Ham Sok-hon: The Korean Gandhi

by Kim Sung-soo

Portrait of Ham Sok-hon courtesy en.wikipedia.org

Ham Sok-hon (1901-1989) was known as the “Gandhi of Korea.” He sought to affirm the identity of Koreans at a time when Korea had fallen prey to Japanese imperialism. Ham believed that discovering one’s identity, especially as a colonized nation, was extremely important as it also determined one’s destiny. Without knowing who you are, it is very difficult to know what to do.

Ham was a civil rights activist when his country was ruled by dictatorial regimes (in both the North and South). Yet, as a maverick thinker, he tried his best to merge diverse religions and ideologies. Although he passed away nearly three decades ago, his legacy still inspires a considerable number of civil rights activists and liberal thinkers in Korea today.

Ham was born in North Korea and died in South Korea. He grew up on a small island in the Yellow Sea at the beginning of the 20th century. His father was a gentle and quiet herbal doctor, while his uncle was a man of action with vigorous Christian faith and a strong sense of patriotism as Korea began to lose her sovereignty to Japan. From an early age, Ham was influenced a great deal by his uncle in terms of merging Christian faith and a spirit of national independence under Japanese oppression.

The March 1 Independence Movement of 1919 was the turning point in Ham’s life, which changed him from a shy boy of eighteen to a courageous young man. From that point on he became very aware of his identity, as well as the identity of his country as a colonized nation. Later, in the 1930s as a history teacher, he began to write what would be Korean history from the oppressed people’s perspective. Because of his view on Korean history, he was imprisoned and suffered greatly at the hands of the Japanese colonial regime. His books, starting with the controversial Korean History in 1948, and the later Queen of Suffering: A Spiritual History of Korea (Seoul, Korea: Friends World Committee for Consultation, 1985) are still recognized as among the most notable books in Korea.

Although Korea regained its independence in 1945, sadly Ham encountered another oppressive regime, the Soviet Union in North Korea. Since he was a Christian activist and took a non-cooperative stance against the communization policy in the North, he was imprisoned by the Soviet military government. So although Korea was “liberated,” still Ham was imprisoned and beaten, this time by the communists as a Korean patriot. What irony!

Man of Suffering and “Foolish Bird”

The Soviet military government in the North tried to force Ham to be a spy for them, and he escaped to the South in March 1947. But as he also criticized the corrupt and dictatorial regimes of Syngman Rhee, Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan successively, Ham was again repeatedly persecuted, tortured and imprisoned by the South Korean regimes. His life was full of suffering. Yet despite his constant suffering, Ham never lost his optimism and sense of hope for humanity, and even provided a vision for his downhearted fellow countrymen.

Although Ham lived under oppressive regimes throughout his entire life, he always stressed the importance of nonviolence and pacifism. At the same time, he eagerly promoted democracy and the freedom of the press, while he heavily criticized the obedient, passive and fatalistic attitude of the people. Perhaps his fundamental thinking can be summarized as “malice toward none” with a strong sense of justice.

While Ham had an open view toward any religion and was happy to stay a maverick thinker rather than promoting a particular religious institution, he was formally a Quaker, a nonsectarian Christian denomination. He regarded the least form of religious institutionalization as the best religion. Ham was especially impressed by the Quakers’ pacifism, egalitarianism, community spirit (group mysticism), and active participation in here-and-now social affairs rather than longing for a “heaven or Kingdom of God” in the afterlife.

At the same time, Western Quakers firmly and steadily backed Ham’s civil rights movement when Korea was ruled by authoritarian regimes. As Quakers tried to merge and keep a balance between science and religion, between rationalism and mysticism, Ham also had such a tendency.

Thanks to Ham’s tireless activities for the democratization movement of Korea with a principle of nonviolence, American Quakers nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979 and 1985, making him the first Korean to be nominated. Ham himself felt that he was unworthy. Nonetheless, his life as a Christian, particularly as a Quaker, was an attempt to find the truth within his specific historical era, an era of political oppression and religious narrow-mindedness.

Ham went by the pen name of “Foolish Bird” or “Albatross.” Perhaps his life-style was the same as the albatross. Though his heart beheld and stayed with the blue sky or idealism, he was not able to earn even a piece of bread to eat. His daily bread was given by his friends and neighbors. In sociological terms, Ham was a marginalized individual. However Lao-tzu, Jesus, Socrates and John the Baptist were also marginalized individuals in their time. Perhaps it was this social marginality that helped to form his unique character.

Despite a life of suffering, poverty and persecution, Ham was free from anger or resentment, thanks to the cultivation and nourishment of his “Inner Light” (strength), as Quakers called it. Ham’s wife may have respected him as a “righteous man,” but living hand to mouth below the poverty line possibly showed him as a man unfit to be the head of a family. Although his son admired him as a great leader of the nation, he also regarded Ham as a “tiger father” rather than a “friendly dad.” Perhaps this was Ham’s limitation as a fragile human being.

Moral Man and Eternal Visionary

Ham left the following legacies for today’s Korea. First, there is democracy. Ham’s activities were the voice of deprived Korean people when the masses had lost their rights, dignity, and a voice for themselves. When, in the minds of countless Koreans, democracy was but a dream, not a reality, Ham was the symbol of the free man and the personification of democratic ideals. It seemed to Ham that democracy was a kind of religion, and that he wanted it to be in a real sense the religion of his fellow Koreans.

Ham also left as a philosophical legacy his idea of the intersection of Western Christianity and Asian philosophies stemming from his view on religious pluralism. He combined the essence of Christianity, such as an awareness of social justice, human rights and protestant spirit, with the essence of Asian philosophies, such as transcendentalism, comprehensiveness and magnanimity. As an alloy of copper and zinc makes a new product, brass, so Ham fused the Asian philosophies and Western Christianity to attain a yet higher stage of humanity.

Due to such legacies, in 2000 Korea selected Ham posthumously as a national cultural figure. His idealistic view can be compared to the position of the Pole Star, which at vast distances can prove to be a more definite marker than a nearby hill. No matter how far one walks in the direction of the Pole Star, one may never reach it. But that is no reason to suggest that the Pole Star is not there or that it is a vain goal. Rather, if one can reach the goal, like the nearby hill, it cannot be used any more as a definite marker.

While Park Chung-hee or Kim Il-sung were considered by some to be heroes on account of their successful economic policy and political indoctrination of the people, respectively, Ham can be considered a moral hero. He was not a dexterous politician, but was a moral man and eternal visionary.

It seems that everyone is born an idealist, but as we grow most of us lose our “natural piety” when faced with the real world, the world of “war against all.” Only a few good people maintain their ideals and dreams, regardless of the harsh conditions of the outside world. Certainly Ham was one of them. Ham was born in Korea, lived with us, and he is still among us in spirit, a man of conscience, a Korean Gandhi.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dr. Kim Sung-soo is the former head of the International Cooperation Team at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Republic of Korea, and currently the UK correspondent for Ohmynews; international.ohmynews.com. He is the author of Biography of a Korean Quaker, Ham Sok-hon, Seoul (Korea): Samin Books, 2001; with thanks to the author and to the Korea Times for permission; koreatimes.co.kr.