Nonviolent Tactics: How Anti-Vietnam War Activists Stopped Violent Protest from Hijacking Their Movement

by Robert Levering

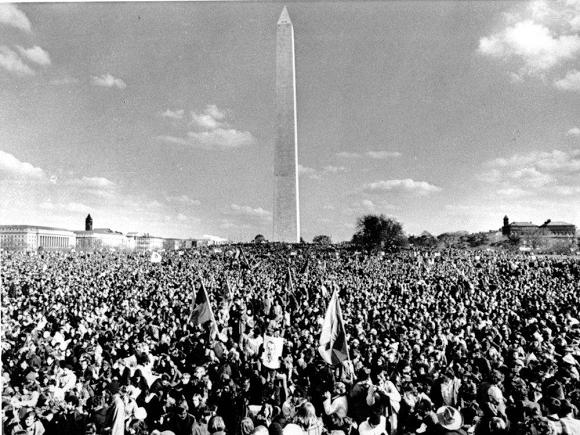

Anti-Vietnam War rally at Washington Monument, Nov. 1969; courtesy npr.org

Only the Vietnam era protests match the size and breadth of the movement unleashed by the election of Donald Trump. One point of comparison: The massive march and rally against the Vietnam War in 1969 was the largest political demonstration in American history until the even more massive Women’s March on January 23. All around us we can see signs that the movement has only just begun. Consider, for instance, that a large percentage of those in the Women’s March engaged in their very first street protest. Or that thousands of protesters spontaneously flocked to airports to challenge the anti-Muslim ban. Or that hundreds of citizens have confronted their local congressional representatives at their offices and town hall meetings about the potential repeal of Obamacare and other Trump/Republican policies.

As activists prepare for future demonstrations, many of us are rightfully concerned about the potential disruptions by those using Black Bloc tactics, which involve engaging in property destruction and physical attacks on police and others [See Chris Hedges’ controversial article about Black Bloc, which we previously posted here]. They often appear at demonstrations dressed in black and cover their faces to disguise their identities. Their numbers have been relatively small to date. But they garner an outsized amount of media coverage, such as a violent protest in Berkeley to block an appearance by an alt-right provocateur or the punching of a white nationalist during Trump’s inauguration. The result is that an otherwise peaceful demonstration’s primary message can get lost in a fog of rock throwing and tear gas. Even worse, fewer people are likely to turn up at future protests, and potential allies get turned off.

This is not a new phenomenon. Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. confronted this issue. So did those of us active in the struggle against the Vietnam War. I played a major role in organizing the national antiwar demonstrations between 1967 and 1971, as well as dozens of smaller actions during that time. Today’s protest organizers and participants can learn much from our experiences on the frontlines half a century ago.

A good place to start is to consider the Weathermen, the most prominent of the counterparts to the Black Bloc in our day. As proponents of violent street tactics, the Weathermen capitalized on an aspect of the 1960′s counterculture that glorified violent revolution. Posters displaying romanticized images of Che Guevara, Viet Cong soldiers (especially women fighters) and Black Panthers with guns were plastered on many walls.

The Weathermen didn’t just spout revolutionary rhetoric. One of their most memorable actions was what they proclaimed as the “Days of Rage.” They urged people to join them in Chicago in early October 1969 to “Bring the War Home.” They recruited extensively among white working-class youths to come to the city with helmets and such weapons as clubs, prepared to vandalize businesses and cars as well as assault police. They believed their action would help provoke an uprising against the capitalist state.

During the “Days of Rage,” the Weathermen did not attach themselves to a larger peaceful demonstration. They were on their own. So, the action provides a great case study about the feasibility of violent street tactics.

For starters, they discovered that it was hard to find recruits for their violent street army. Only about 300 people showed up despite months of effort. And they found it harder to enlist support for their actions even among those who were friendly towards them politically. In fact, Fred Hampton, the leader of the Black Panther Party in Chicago, publicly denounced the group’s action, fearing it would turn off potential allies and lead to intensified police repression. “We believe that the Weathermen action is anarchistic, opportunistic, individualistic, chauvinistic and Custeristic [referring to General George Custer’s suicidal Last Stand]. It’s child’s play. It’s folly.”

It would not be overstating the case to say that the “Days of Rage” was a flop. They did trash some stores and engage in fights with police. But Chicago police easily contained their violence and rounded up virtually all of the militants and charged them with stiff crimes. Some suffered serious injuries, and several were shot by the police (none fatally). The Weathermen soon gave up on violent street protests, became the Weather Underground and confined themselves to bombings of “symbolic” targets such as police stations and a bathroom in the U.S. Capitol.

In point of fact, the “Days of Rage” showed the ineffectiveness of violent street tactics. The Black Bloc anarchists understand this reality, too. They need us as a cover for their actions. Put another way: We don’t need them, but they need us. So, the primary way to deal with those who advocate violent tactics is to isolate them, do everything possible to separate them from the peaceful demonstration. That was one of our goals when organizing the November 15, 1969, antiwar march on Washington, D.C.

As organizers, we knew that it was not enough to stop potential disrupters. We knew we had to make sure that the demonstration itself would channel people’s indignation with the war more creatively than yet another conventional march and rally. People take to the streets because they are upset, angry or disillusioned. They want to express their outrage as powerfully as possible. Although some people prefer disruption for its own sake, almost everyone else wants to deliver their message so that it leads to positive social change, rather than makes matters worse.

We adopted a tactic first used by a group of Quakers the previous summer. To personalize the war’s impact, the Quaker group read the names of the American soldiers killed in Vietnam from the steps of the Capitol. Their weekly civil disobedience action received a lot of media attention, particularly after some members of Congress joined them. Before long, peace groups throughout the land were reading the names of the war dead in their town squares and other public spaces.

For our demonstration in Washington, we planned what we called the “March Against Death.” Here is how Time magazine described it at the time:

Disciplined in organization, friendly in mood, [the march] started at Arlington National Cemetery, went past the front of the White House and on to the west side of the Capitol. Walking single file and grouped by states, the protesters carried devotional candles and 24-in. by 8-in. cardboard signs, each bearing the name of a man killed in action or a Vietnamese village destroyed by the war. The candles flickering in the wind, the funereal rolling of drums, the hush over most of the line of march — but above all, the endless recitation of names of dead servicemen and gutted villages as each marcher passed the White House — were impressive drama.

First in line was the widow of a fallen serviceman, followed by 45,000 marchers (the number of Americans killed in the war to that date). After walking the four-mile route, the marchers reached the Capitol, where they placed their placards in coffins. The march began the evening of November 13 and went on for 36 hours. No one who was there would ever forget. It also set the tone for the later massive march and rally.

While the “March Against Death” was taking place, we were busily training marshals who would oversee the demonstration — that is, essentially be our own force of nonviolent peacekeepers. We were rightfully concerned that groups of Weathermen-style protesters would disrupt our demonstration regardless of how creative our tactics were. The Chicago action had taken place only a month earlier, and we knew that there were many individuals and small groups for whom the appeal of violent street tactics had not diminished.

With the help of several churches that provided us with spaces, we recruited trainers, many with previous experience in nonviolent training. After giving an overview of the march’s objectives and logistics, we had the trainees do several role-playing exercises. For instance, we had a scenario where a group of Weathermen-style protesters tried to disrupt the march by trying to get people to join them in more “militant” actions. One tactic we suggested was to get the marchers to sing the then-popular John Lennon tune “Give Peace a Chance” to divert attention from the disrupters. Another was to get the marshals to link their arms to separate the disrupters from the rest of the marchers.

At the end of the two-hour-long session, the newly trained marshals were given a white armband and told where to meet the next day. We trained more than 4,000 marshals who were deployed along the entire route of the march. The armbands were an important symbol to help us isolate would-be disrupters.

Although there were a few incidents after the rally had broken up, they did not detract from the powerful message that the half-million war opponents in Washington conveyed to the public and the nation’s leaders. The war didn’t end the next day, or even the next year, but the peace movement played a major role in stopping it — something that was unprecedented in American history.

Not everyone was pleased with our marshals. In Clara Bingham’s interview of Weathermen leader Bill Ayers for her recently published book, Witness to the Revolution: Radicals, Resisters, Vets, Hippies, and the Year America Lost Its Mind and Found Its Soul (New York: Random House, 2016) Bill Ayers says: “…the problem with the mass mobilizations at that time was that the militants — us — were always contained. We were pushed aside by peace marshals and demonstration marshals.”

The man in the White House also did not like the peaceful character of our actions. The historian Rick Perlstein in his Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America (New York: Scribner, 2009) tells a story that indicates what kind of protest Richard Nixon would have preferred: “A briefing paper came to the president’s desk in the middle of March [1969] instructing him to expect increased violence on college campuses that spring. ‘Good!’ he wrote across the face.”

This anecdote points out another significant lesson from the Vietnam era. Governments invariably welcome violent protests. With soldiers, police and huge arsenals of weapons, they know how to deal with any form of violence. They also infiltrate protest groups with provocateurs to stir up violence — something we experienced repeatedly then and is certainly happening today. The Black Bloc is especially vulnerable to infiltration because of their anonymity. And, as we learned then, those in power will willfully mischaracterize peaceful demonstrators as violent to help turn those in the middle against us.

What makes any resort to violence, including property destruction, on the part of the movement especially dangerous today is the current occupant of the White House. Most of us have seen video clips of the campaign rally last year where Trump said he would like to see a heckler “carried out on a stretcher.” We can only imagine what this man would do if given any excuse to fully deploy the forces of violent repression against us. Nor can we forget that this man has shown a willingness, if not eagerness, to encourage his gun-toting supporters to turn on his opponents.

The movement must keep its focus on the issues. We must not allow ourselves to get distracted. Too many lives are threatened by Trump’s reckless rhetoric and heartless policies. We can succeed, just as we did in stopping the Vietnam War. It will take time, but we can create a more just and peaceful society. It starts with us.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Robert Levering was a full-time peace activist from 1967 to 1973, helping organize demonstrations for the New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, Peoples Coalition for Peace and Justice, the Honeywell Project, a Action Group, and the American Friends Service Committee. He is on the board of Peaceworkers. Posted in conjunction with wagingnonviolence.org (March 7, 2017), per the Creative Commons agreement.