The Spirituality of Nonviolence: The Soka Gakkai International Quarterly Interview with James Lawson

by SGI Quarterly

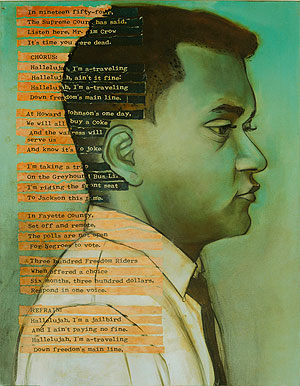

Painting by Charlotta Janssen based on mug shots of James Lawson after his arrest for a nonviolent protest in Jackson, Mississippi; courtesy charlottajanssen.com

Interviewer’s Preface: In the late 1950s, James Lawson moved to Tennessee as southern secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, where he began training students in Nashville in nonviolent direct action. Prior to that, he had spent a year in jail as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, and had also trained in nonviolence at various Gandhian ashrams in India. Described by Martin Luther King Jr. as “one of the foremost nonviolence theorists,” Rev. Lawson, now in his 80s, still remains a vibrant voice for social justice. SGI

SGI Quarterly: Do you remember a particular moment after you became involved in the Civil Rights Movement when you felt afraid?

James Lawson: I recall a number of moments of fear. But, I should say to you that those are isolated moments, and that from the beginning of my involvement character requirements froze out any fear. I was going to finish my graduate degree and then probably move south to work in the movement. I had spent three years in India, 1953-56, and then came back to Ohio for graduate school. I shook hands with Martin Luther King for the first time on February 6, 1957. By then I had been practicing and studying Gandhian nonviolence for ten years. And so as we met and talked, he said I should come south immediately. I said to him, “OK, I’ll come just as soon as I can,” which meant that I dropped out of graduate school and moved. There was no fear in making that move.

I don’t recall a single moment as I traveled around the South that I was frightened or fearful. And as we began the Civil Rights Movement in Nashville, I wasn’t aware of any moment of fear there either. I was expelled from the university and was made the target of many public attacks.

This is the movement that produced Diane Nash, Congressman John Lewis, Bernard Lafayette, C. T. Vivian, and a whole wide range of other people. Well, some of those people write about the fears they had in doing what they were doing. I had no such fear as we did it. Why? And of course for Diane and John Lewis and others, their fears largely evaporated as soon as we got past the first public demonstrations. Because they realized that they were fighting against that which is wrong—they knew that segregation was wrong, but they had not been given any clues as to what might follow after defeating it. Our workshops in Nashville gave them the nonviolent tools for civil resistance. Once we got past the first two weeks of demonstrations and the first face-to-face encounters with violence and the first arrests, they had no fears.

Fear is an issue of character, of building character. Courage is not merely, or primarily, the absence of fear. It is the taking on of tasks and concerns that are larger than the fear. It is discovering how to face your fears and moving through them as a whole person. That is what is essential. I know the testimonies of some of these persons with whom I worked back then; they discovered within the conquest of fear. Now, for all of them there may have been certain times when the fear was very strong, but they managed by virtue of the tasks they had assigned themselves to walk through those fears and overcome them.

SGIQ: How did you train young activists in nonviolence?

Lawson: We taught them about concrete experiences, of black people, Europeans and Asians, about nonviolent behavior in conflict situations. I gave them a picture of Jesus of Nazareth as a nonviolence practitioner, and an interpretation of his life from the point of view of his direct action. I especially gave them the methodology of Gandhi, as I and others had come to summarize it in 1957-58, and made him and his independence movement a major illustration of what nonviolent power can do. I put together a curriculum that helped them see that there were people not much different from ourselves who had decided that there was a better way of changing evil, rather than imitating it; and that Gandhi had called all of that nonviolence.

Secondly, we tried to come to grips with the dynamics of segregation, what it was really all about, what downtown Nashville was about and how it economically deprived and excluded people. Then we did a series of role-playing exercises to help them face the possibilities of certain scenarios both personal and then in a broader political context. We gave them the tools to live with tension and fear, to have a different vision and recognize that they have the resources within themselves to exercise that different vision.

With fear, if you follow it from the perspective of adrenalin, it will mislead you in your humanity. But if you follow the fear through the perspective of your character at its best or through the task of doing good—justice that needs to be done, the tasks at hand—then the fear becomes an ally for your work.

SGIQ: Is it right to say that the courage of the activists created a change in the hearts and attitudes of their opponents?

Lawson: Well, there is such a thing as a spirituality of nonviolence, the inner resources that one can shape and exercise that allows for the conquest of fear in a great variety of personal and social situations.

In the movement back then, society used two or three major tools to reinforce the racism. There was the threat that if you do not obey, do not conform to the white status quo, you are going to be punished. The second threat was the threat of actual violence. The third was that you would be arrested. And so in our workshops we tried to deal with all three of those elements that made possible Jim Crow segregation.

In the Nashville movement in 1960, we developed a spirit of laughing at all three of those threats. Among the students, and among the adults in the Movement, those threats were destroyed in our minds and hearts, and in the activity of the movement. So those powers that society had in Nashville for preserving segregation were no longer there in the minds of the people in the movement.

During the bus boycott, Martin Luther King said that the movement saw the “emergence of a new negro” in Montgomery, because people who joined the bus boycott basically told society, “You can threaten us, but it won’t mean anything to us. You can use violence against us. We are not going to be intimidated by it, and you can arrest us and we are not going to fear going to jail for the cause.” When the city government took out warrants against some 90 or 100 black folks in the boycott, people shocked the community and the police and the mayor, because they went to the police station to turn themselves in. The police had never heard of such a thing.

When the first group was arrested and officially booked, other people gathered. So there were some 90 other people outside the jail waiting to be booked and wanting to be booked and very cheerful about it. Well, that had never happened before in this country in these dimensions. So, it was astonishing that blacks, who had kept their place for 60 years, now suddenly were asking to be arrested. The threat of jail was no longer a threat.

SGIQ: Is nonviolence a strategy, or is it more than that?

Lawson: I know there are people who see and use it only as a tactic. But I don’t know what that means, because we human beings are not “tacticians.” We have more going on in our minds and spirits. For human beings to act, we must have faith, confidence, trust in what we do, whatever the methodology is, whatever the tactic is. And if we have doubts and fears that what we are doing will not work, we’re finished.

When Gandhi says nonviolence is a social science for social change, I think he’s including the intellect, the heart, the personality, the emotions, the tactics, the methodology and the philosophy that you have to develop to make this work. And I think it does become a lifestyle, just as when you launch a professional military career you develop a lifestyle, or when you become a lawyer you develop a lifestyle. In that lifestyle I think you can analyze methods and tactics versus spirituality, character. But in human beings it becomes a whole cloth, a whole garment.

Today in Western civilization we have this massive mythology that the way you effect change is through violence, and that violence offers effective change. So nonviolence comes along and offers a critique of war, a critique of violence; offers an alternative. We don’t think violence has worked.

SGIQ: Many people are concerned about the state of the world. What do you think is necessary to galvanize people to stand against social injustices today?

Lawson: Basically to understand that you embrace the nonviolent politics that was represented by the Civil Rights Movement: the politics of participation and engagement; developing the empowerment of people who blend their power together to put into the public agenda a new measure of power that can challenge the old powers.

When people collectively come together and strategize and plan, working together and acting together, they create a power they can effectively use in their situation to effect change.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The American activist James Morris Lawson, Jr. (b.1928) is professor emeritus at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. He was a leading theoretician and tactician of nonviolence in the Civil Rights Movement. During the 1960s, he served as a mentor to the Nashville Student Movement and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and to this day continues to train activists in nonviolence. The SGI Quarterly is a publication of Soka Gakkai International, as it states on their website, “a worldwide association of 93 constituent organizations with membership in over 190 countries and territories which aims to develop the potential for hope, courage and altruistic action. Rooted in the philosophy of Nichiren Buddhism, members of the SGI share a profound commitment to peace, culture, and education.” The name of the interviewer is not given on the site; courtesy www.sgiquarterly.org.