John Lewis and the Spirit of Selma

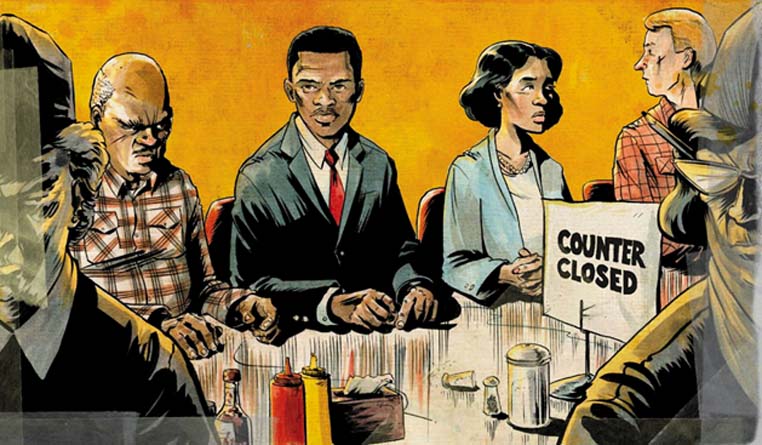

John Lewis at Nashville sit-in, book cover of March: Book One, courtesy topshelfcomix.com

Editor’s Preface: John Robert Lewis (b. 1940) is the U.S. Representative for Georgia’s 5th congressional district, and the dean of the Georgia congressional delegation. His district also includes the northern three-quarters of Atlanta. His Wikipedia page is a reliable starting point for information about his nonviolent civil rights activities and his political career. JG

It has now been 50 years since “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama, when John Lewis and Hosea Williams led some 600 civil rights marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7, 1965. The demonstrators attempted to march peacefully from Selma to Montgomery in support of voting rights, but state and local police viciously attacked the nonviolent procession, brutally beating them with whips and clubs, firing tear gas and charging the defenseless marchers on horseback. Hundreds of people suffered bloody beatings and some were clubbed nearly to death.

Fifty years have passed and yet Rep. John Lewis remains just as strongly committed to the Freedom Movement’s vision of nonviolent social change, just as dedicated to building a world based on its values of love, peace and human rights. On February 18, 2015, 50 years after Selma, Lewis spoke to a gathering in San Francisco and vividly recalled the moment when the marchers first encountered Alabama state troopers and local police on the bridge. “We got to the highest point on the Edmund Pettus Bridge,” Lewis said, “and down below we saw a sea of blue — Alabama’s state troopers. And behind the state troopers we saw the sheriff’s posse on horseback.” Major John Cloud told the civil rights marchers they were conducting an unlawful march, and when Hosea Williams asked him for a moment to pray, the major said, “Troopers advance!”

Lewis soberly described what happened next, in the first moments of the police attack before he lost consciousness. “You saw these men putting on their gas masks. They came towards us, beating us with nightsticks, trampling us with horses and releasing the tear gas. I was hit on the head by a state trooper with a nightstick. My legs went out from under me. I fell to the ground. Apparently, I lost consciousness. The doctor said I had a concussion. I thought I was going to die on that bridge. I thought it was my last nonviolent protest. But somehow I survived. And a group of nuns took care of us at a local hospital.”

This police assault on the Selma marchers is also brought back to life in the first pages of March: Book One (Marietta, Georgia: Topshelf Productions, 2013), a graphic novel by John Lewis, co-author Andrew Aydin and artist Nate Powell that offers a highly personal, eyewitness account of the civil rights movement.

When Lewis was a young man, he was greatly influenced by a widely distributed comic book, Alfred Hassler and Benton Resnick’s Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story (New York: Fellowship of Reconciliation Publications, 1958), a pictorial history of the Montgomery bus boycott published by the Fellowship of Reconciliation. The comic book influenced Rep. Lewis to work with Congressional Aide Andrew Aydin to create a trilogy of graphic novels about the Selma marches and the entire Freedom Movement of the 1960s. March, books 1, 2 and 3 are New York Times bestsellers and the first graphic novel to win a Robert F. Kennedy Book Award.

Selma More Timely Than Ever

Even though it has been 50 years since the march on that Bloody Sunday, the story and lessons of Selma have perhaps never been more timely and meaningful. Fifty-year anniversary events are being held in honor of this turning point in the struggle to win voting rights. The excellent movie, Selma, is telling the history of the struggle for a new generation. Also, the nationwide protests of the police killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner are a reminder that social-change movements are needed more than ever.

Rep. Lewis spoke about his experiences in the civil rights movement at the San Francisco Public Library (February 18, 2015) just three days before his 75th birthday. Lewis was a 25-year-old firebrand activist when he delivered his brilliant, outspoken speech at the massive March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (August 28, 1963), a speech that was so uncompromising in its militant demands for justice and freedom that march organizers pleaded with him to tone it down.

Fifty years later, in his speech in San Francisco, the 75-year-old Lewis proved to be an extraordinarily eloquent and inspiring teacher in conveying the lifelong lessons in nonviolence he learned during Nashville sit-ins, Freedom Rides in Alabama, Mississippi Freedom Summer, and during the Selma marches. But Lewis is much greater — much deeper — than merely a skilled orator. He speaks in a modest, somewhat unassuming way, without overly dramatic flourishes, yet he connects with people at a very profound level, because he speaks from some deeply thoughtful place within.

His stories about nonviolent resistance to racism and oppression have an eye-opening impact. Both in his public speeches and in the pages of his graphic novels, his storytelling is so vivid and realistic that he is able to make his listeners feel the life-and-death stakes of the struggle for freedom that fell on the shoulders of very young activists in the 1960s. As a young man, Lewis was often on the radical, cutting edge of nonviolent resistance. Today, he is one of the nation’s most powerful voices for the values of nonviolence, love, peace and justice.

John Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, on a small farm near the tiny town of Troy, Alabama. His parents were sharecroppers who finally were able to buy their land and raised hogs, peanuts, cows, cotton, corn — and chickens. In his speech in San Francisco, Lewis recalled those days with affection, especially his childhood years of raising chickens. Lewis was too tenderhearted to cooperate in selling his chickens or letting them be killed for food, preferring instead to preach to his barnyard congregation of chickens. I couldn’t help but recall St. Francis preaching to the birds.

Getting into “Necessary Trouble”

As a child, when his family visited the towns of Montgomery, Tuskegee and Birmingham, Alabama, Lewis noticed the signs that said, “White Men, Colored Men, White Women, Colored Women.” At the movie theaters, he said, all the black children would go upstairs to the balcony and all the white children would stay downstairs. Lewis said, “I would ask my parents and grandparents, ‘Why?’ They would say, ‘Well, that’s the way it is. Don’t get in the way. Don’t get in trouble.’”

In 1955, when Lewis was 15 and in high school, he heard about the arrest of Rosa Parks because she refused to go to the back of the bus. “The action of Rosa Parks and the leadership and words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. inspired me to find a way to get in the way, to get into trouble,” Lewis said. “And I got into trouble — necessary trouble!”

Inspired by Dr. King and Rosa Parks, Lewis went to the Pike County Library in 1956 when he was 16, and tried to check out books. “The librarian told us that the library is only for whites and not for coloreds,” he said.“ I never went back to the Pike County Pubic Library again until July 5, 1998, for a book signing for my first book, Walking with the Wind. Hundreds of black and white citizens showed up.”

After a large reception and book signing, the library gave him a library card, 42 long years after the 16-year-old Lewis had been denied one. “It says something about the distance we’ve come and the progress we’ve made in laying down the burden of race,” Lewis said.

A Progressive Congressman

Lewis himself has come a long way from that small farm in Alabama. He was elected to the House of Representatives in Georgia’s 5th District in 1986. Today, he is one of the most progressive members of Congress, speaking out for national health insurance, gay rights, and measures to fight poverty. He sponsored the Peace Tax Fund Bill to give taxpayers a way to conscientiously object to military taxation, and he opposed NAFTA and the Clinton administration’s attacks on welfare.

Learning Nonviolence

While the college-age Lewis was attending American Baptist Theological Seminary and Fisk University in Nashville, students from several colleges began attending nonviolence workshops conducted by Jim Lawson. Lawson “had lived in India and studied the way of peace, the way of love, the way of nonviolence,” Lewis said. Along with strategy sessions and role-playing, “We became imbued with the way of peace, with the way of love, with the way of nonviolence. Many of us started accepting the way of nonviolence as a way of life, a way of living.”

That all sounds very lofty and utopian until we consider that these very young men and women began putting the ideals of love and peace into action in a climate of extreme violence and racial intolerance. They had to find the strength to endure the hatred directed at their nonviolent protests by thousands of white people who defended the system of segregation with acts of brutality and bloodshed. Another great figure in the history of nonviolence, Dorothy Day, quotes Dostoyevsky as saying: “Love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing compared to love in dreams.”

In his recent speech in San Francisco, Lewis described the sit-ins of the Nashville Student Movement when college students risked their lives in an effort to integrate lunch counters, restaurants and movie theaters. “You’d be sitting there in an orderly, peaceful, nonviolent fashion waiting to be served, and someone would come up and spit on you, or put a lighted cigarette out in your hair or down your back, or pour hot coffee on us, or pull us off the lunch-counter stool. You’d just look straight ahead.” Neither threats nor beatings nor jail could shake their commitment to freedom for their people.

The Last Supper

Lewis had just turned 20 the week before he was first arrested. “The first time I was arrested was in February 27, 1960,” he said. “I felt liberated. I felt like I’d crossed over. So I said to myself, ‘Arrest us, jail us, beat us, what else can you do?’ We started singing, ‘I’m not afraid of your jail.’”

His next trial by fire was on an interstate bus trip through the Deep South. Lewis was one of the first Freedom Riders, an integrated group of black and white activists who boarded a Greyhound and a Trailways bus in Washington, D.C., in an attempt to pressure the U.S. government to uphold the 1960 Supreme Court decision that had declared segregated interstate bus travel to be unconstitutional.

On May 3, 1961, the night before the first Freedom Riders left Washington, D.C., the group of 13 activists gathered at a Chinese restaurant. John Lewis, the young man from Troy, Alabama, had never been to a Chinese restaurant before. “It was wonderful,” he said. In the middle of the “wonderful meal,” a member of their group reminded them all of the life-and-death nature of their mission. He said, “As you eat, remember this may be like the Last Supper.”

This meal is compellingly portrayed in March: Book Two, (Marietta, Georgia: Topshelf Productions, 2015) with a full page showing the names and faces of each of the Freedom Riders. After the Last Supper remark, Lewis wrote, “We all knew what he said was true — the wills we’d signed that week served as testament.” The next day, May 4, 1961, members of the group boarded the two buses and left Washington, D.C., to travel through the South as an integrated group.

Lewis was literally floored by an attack that took place a few days later in Rock Hill, South Carolina, when he and his seatmate, a white man named Albert Bigelow, “tried to enter a so-called white waiting room. Members of the Klan attacked us and left us lying in a pool of blood.” When the white men began assaulting John Lewis, Bigelow stepped between him and his attackers, trying to protect Lewis, but the mob started beating Bigelow, pounding him to the floor. Bigelow had been a U.S. Navy Commander in World War II, but then became a pacifist. In 1958, Bigelow sailed his four-man ship, The Golden Rule, into the atomic testing site in the South Pacific to disrupt U.S. nuclear weapons tests in the Marshall Islands.

After Lewis and Bigelow were beaten to the ground and bloodied, the police arrived and asked if they wanted to press charges. “We said, ‘No, we come with peace and love and nonviolence.’ They left us bloodied. The Freedom Rides continued.”

The Burning Bus

When their buses pulled into Anniston, Alabama, on May 14, a racist mob and the Ku Klux Klan attacked the Greyhound bus, slashed its tires, then firebombed it a few miles outside of town, and began beating the Freedom Riders as they escaped the burning bus. Shortly after that first bus was burned, the second bus arrived in Anniston, and Klansmen boarded it and brutally beat the Riders. Walter Bergman, age 61, was beaten nearly to death and repeatedly kicked in the head, causing permanent brain damage. He soon suffered a severe stroke that left him paralyzed and in a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

As nightmarish as was this violence, the Freedom Rides were a trailblazing achievement on the road to civil rights. The entire nation witnessed the unbelievable courage of the Freedom Riders, and became more aware of the deadly levels of brutality and hatred being used to preserve the system of racism and segregation.

When Lewis was describing for us the way he and Bigelow refused to press charges against their assailants, I was stunned to hear how a 21-year-old man found the forgiveness to say, “We come with peace and love and nonviolence.”

Yet, this story has an even more unforgettable ending. In February of 2009, one of the Klan members who had taken part in the beating of Lewis and Bigelow came to visit Rep. Lewis in his Washington office. Elwin Wilson was now in his 70s, and he came with his son, in his 40s. The man said to him, “Mr. Lewis, I’m one of the people that attacked you and your seatmate. I want to apologize. Will you forgive me?” As Lewis told it, he said to the man, “‘Yes, I accept your apology. Yes, I forgive you.’ And that man, he started crying. His son started crying. They hugged me. I hugged them back. And I started crying.”

We are one family. We all live in the same house,

not just the American house, but the world house.

Lewis said he visited with “this gentleman” three other times, and he told us what this encounter truly meant, and what the spirit of nonviolence was all about. Lewis said, “That is the power of the way of peace, the power of the way of love, the power of the way of nonviolence — to be reconciled. In the final analysis, we are one people. We are one family. We all live in the same house, not just the American house, but the world house.”

This lesson was given to us by a man who had lived through a lifetime of segregation and cruel mistreatment; who had endured many beatings from violent mobs and unjust jail sentences at the hands of racist police, a man who saw buses burning, who endured the hellish conditions of Mississippi’s infamous state penitentiary, Parchman Farm, and who was part of a movement where too many friends and ministers and activists and Sunday School students were murdered and martyred.

Shining Vision of Hope

It is horrible what this nation allowed to happen to idealistic young people who gave so much of themselves — sometimes even their very lives — in the struggle for freedom and equality. It is a terrible crime that our nation has never fully atoned for. Yet, Lewis ended his presentation in San Francisco with a shining vision of hope about creating Martin Luther King’s beloved community.

He said, “I must tell you tonight that in spite of 40 arrests, jailings, and being beaten and left bloody not only in Rock Hill, South Carolina, but at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery where I was hit on the head by a member of an angry mob with a wooden Coca-Cola crate, I am still hopeful, still optimistic. We must never, ever give up. We must never, ever give in. We must never get lost in a sea of despair. We must keep the faith. I’m not going to turn back. And you must not turn back. You must not give up. You must not give in. We can create the beloved community here in America.”

Those who were able to listen to John Lewis in San Francisco were amazed and illuminated by his spirit. One of the most radical champions of civil rights, one of the strongest fighters from the movement days of the 1960s, is also one of our most eloquent defenders of love and peace.

You must continue to spread the good news,

the way of love, the way of peace, the way of nonviolence.

His last words that night shine like the stars. They should be engraved as a living legacy on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. John Lewis said, “You must continue to spread the good news, the way of love, the way of peace, the way of nonviolence.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Terry Messman is a regular contributor to this site, and the editor and designer of Street Spirit, a street newspaper published by the American Friends Service Committee and sold by homeless vendors in Berkeley, Oakland, and Santa Cruz, California. Please click on his byline to view his Author’s page, for an index of his interviews and articles.