“Peace and Love”: The Street Spirit Interview with Country Joe McDonald, Part Two

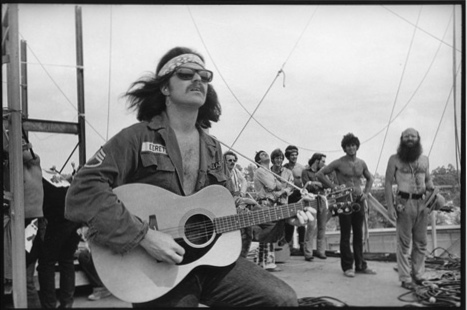

Country Joe McDonald sings “Fixin’ to Die Rag” for 300,000 people at Woodstock; photo by Jim Marshall, courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“It was magical. All at the same time, amazing stuff happened in Paris, London, and San Francisco — and BOOM! Everybody agreed on the same premise: peace and love. It was a moment of peace and love. It was a wonderful thing to happen. And I’m still a hippie: peace and love!” Country Joe McDonald

Street Spirit: During the Vietnam War, and while caring for the victims of PTSD and Agent Orange in the years after the war, Lynda Van Devanter and other Vietnam combat nurses helped many veterans to survive. Your song about Van Devanter says that the combat nurse is everybody’s savior but her own. Then it asks, “Who will save her now?”

Country Joe McDonald: Yes, who will save her now?

Spirit: Well, who will save her?

McDonald: That’s the question. I don’t know. I’m sort of the Greek chorus. I just ask these questions, and give a voice to people who don’t have a voice. That’s one of the things I do in that song.

Spirit: Did you feel that Van Devanter and Florence Nightingale had experienced so much death and destruction, that they suffered the same kind of post-traumatic stress as a combat soldier?

McDonald: Absolutely! Absolutely! Or the stress of a rape victim. Or any inexplicable, sudden trauma. You don’t get over being raped.

Spirit: Van Devanter was one of the very first women to speak out publicly and remind the nation of how many women served in Vietnam. Didn’t she also write a book about her experiences in Vietnam?

McDonald: She wrote Home Before Morning. It’s her autobiography. Great book. The first woman to write about this — and there haven’t been a lot. China Beach, the TV show, was based on her book and her experiences in Vietnam.

Spirit: Lynda helped so many people with PTSD and Agent Orange ailments, but she herself died in 2002 at the age of 55 due to her exposure to Agent Orange. How were you affected by her death?

McDonald: Lynda and I participated in a few veterans things together and I liked her very much. She was the person that sent me on my journey to discover and explore the life of Florence Nightingale. Just her presence as a visible female soldier and Vietnam veteran opened doors to other women and introduced the public to the reality of women in the military. Even today, women are for the most part invisible.

Over the years, I was a witness to her health problems getting worse and worse. Like so many others who died of war-related wounds, her death was tragic. Had she lived, she would have been such a strong witness to the realities of war from the female perspective.

I don’t think anyone picked up where she left off. That is, of course, sad. We so need to de-romanticize war in order to stop it, and she was working towards that end. For me personally, I felt I lost a friend and comrade and felt so sorry for her daughter and husband.

Her book Home Before Morning about her life and the Vietnam War, and the collection of poems she did with Joan Furey, Visions of War, Dreams of Peace, are must-reads for anyone who thinks that they know about war.

Even after her death, she can continue to open your mind about military women and war, like she did for me. I really miss her very much. Vietnam veterans continue to die every day from war-related wounds and very little is done about it. So sad.

The Heroic Work of Florence Nightingale

Spirit: Everything you have learned from Lynda Van Devanter and Florence Nightingale must have even more impact considering how many members of your immediate family are nurses.

McDonald: My wife Kathy is a labor and delivery nurse and midwife. My niece is a nurse in San Francisco. My daughter just became a nurse. My brother retired as a nurse practitioner from Kaiser after 36 years. And, of course, my mother was named Florence. Another coincidence in my life.

Spirit: Why did you become so captivated by Florence Nightingale that you made a pilgrimage to England to visit her home and amassed a huge archive about her life?

McDonald: I identified with her a lot. I identified with her being misunderstood by her family, and being isolated, and the way she was following a call. Her family had two homes. They had a country home and their main home. In their main home, they had 70 gardeners. Florence had her own French maid her whole life. She was part of the upper class. Her family was part of the 20,000 families that owned England at that time. So she could have lived in luxury her entire life, and was never expected to work. Yet she worked herself to exhaustion in a horrifying war zone.

When she went off to study nursing in Germany at the age of 33, it was the first time in her life that she had ever dressed herself and done her own hair. And she went from that into the hell of the Crimean War with 2,000 deaths in her first year, and dysentery, bleeding, vomiting, moaning and groaning. Then she went on after that to sanitize the country of India. Her story is incredible. And the other thing that fascinated me is how ignored she is. Almost nobody idolizes Florence Nightingale today — except me.

She was one of the most courageous and compassionate leaders the world has known, and the founder of nursing. Her achievements are on the same level as Gandhi or Martin Luther King, yet she’s not honored as they are. There hasn’t even been a realistic movie made about her. She’s almost forgotten now. And even though her name is still known, she was, and is, misunderstood.

Spirit: In your “Tribute to Florence Nightingale”, you described her nursing 2,000 dying soldiers in the Crimean War. She called them “living skeletons, devoured by vermin, ulcerated, hopeless, speechless, dying as they wrapped their heads in their blankets and spoke never a word.” Then she says something amazing: “I stand at the altar of the murdered men and while I live I fight their cause.”

McDonald: Isn’t that beautiful? Isn’t that gorgeous?

Spirit: It’s electrifying. And you recite those words with a lot of urgency. Why did you want to make those words come alive for a modern audience?

McDonald: Oh, I just love it! Because in the first part of what you just read, she gives you her credentials. She tells you that she personally knows what she is talking about. She had this personal experience of war that caused a change in her life and caused her to be transformed. She said, “I stand at the altar of the murdered men.”

I love the word “murdered.” MURDERED. These men were murdered. They didn’t serve their country. They were murdered. They were murdered not by the enemy — they were murdered by war. They were murdered by their government. They were murdered.

And as long as I live, she said, I’ll champion their cause, because they don’t have a voice of their own. And she did it. She did it! For the rest of her life, she did it!

Spirit: Another highly moving moment in your tribute is when she said, “I will never forget.” You really emphasized the importance of those words.

McDonald: That’s the thing that really got me. And that’s the thing that got me with the other Vietnam War nurses. They also found out: “I can never forget.” Those are Florence Nightingale’s own words: “I can NEVER forget!” And she wrote it on pieces of paper for the rest of her life. “I can never forget.” She took extensive notes, and wrote constantly, just volumes and volumes of stuff. And she was always writing: “I can never forget.”It means, of course, that she wants to forget it, but she can never forget it! And that drove her on, that she could never forget the experience of war.

Haunted by War

Spirit: On the one hand, it was like a sacred trust for her to never forget the soldiers who had died. But on the other, she can’t forget because she was always haunted and traumatized by their deaths.

McDonald: She was haunted! She was haunted! Like everybody is haunted when they’re the trauma-victims of war. And everybody has his or her own capacity. She attended to 2000 deaths and she could never forget that. But we don’t know what our own capacity is. We like to think, “Well, I could be a firefighter. I could be a soldier. I could be an emergency medical technician. I could be a doctor. I could help somebody through cancer.” But we don’t know. We don’t know what our capacity is. It could be the smallest thing or the largest thing. It can be one death or two deaths or one frightening thing. But there are things that happen in your life that cause you to say: “I can never forget.”

Spirit: You said that after the Crimean War, she carried that nervous condition with her until she died at the age of 90.

McDonald: There are a lot of theories about it. One is that she suffered from brucellosis (or Crimean fever), and maybe she did. Maybe she had lead poisoning or mercury poisoning. But part of the mix, the gestalt that made up Florence Nightingale, was her war experiences. The other fascinating thing about Florence Nightingale was that in an age when women did not have careers, she chose to have a career. She chose to never get married. She decided she didn’t want to do that. She was going to have a career.

Spirit: In many ways, she was a woman who opened doors.

McDonald: That’s right. She walked that road. She broke those doors down. She is very interesting.

The Permanent Damage of War

Spirit: The thread that runs through nearly everything you’ve said in this interview is the terrible damage caused by war — combat nurses who can never forget, veterans who go on suffering long after the war is over, families who were blown apart just as much as their soldier sons were blown apart. What does all this have to say to governmental leaders who wage wars that will cause permanent damage and suffering to countless people?

McDonald: I love Kurt Vonnegut, and he wrote a book called The Sirens of Titan. It’s a really great book. I’ve read it so many times. He talks about the Tralfamadorians who would think in the form of a cloud above their planet. A cloud would form above their planet and all their consciousnesses would merge into one and they would make decisions.

[Editor: The Tralfamadorians also appear in Slaughterhouse-Five where Vonnegut writes: “All moments, past, present and future, always have existed, always will exist. The Tralfamadorians can look at all the different moments just the way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains, for instance. They can see how permanent all the moments are, and they can look at any moment that interests them.” TM]

We don’t have such a thing. So in making decisions about war, we have governmental bodies. We have the rule of law. We have customs and ethnicities and grudges that go back for generations that prevent us from merging our consciousness together. We do have a collective consciousness of being a planet now, because we’ve seen pictures taken from outer space that show we are a planet, and we are on a sphere, and we are a species on this planet of sapient beings.

But we haven’t developed the ability to communicate collectively. So without that, we’re at a loss. We’re at a loss and we don’t know what to do. How do we decide these great questions of war and peace? What can we do? I don’t know.

In my own consciousness, there are the civilians, and then there are the veterans; there are the anti-war people and the pro-war people. What we need is a dialogue, but how do we have a dialogue? How do we have a collective dialogue with seven billion people? Seven billion people! But we need to have a dialogue. Don’t we need a dialogue to decide these things?

Spirit: Albert Einstein looked to international law and the prosecution and abolition of war crimes, the strengthening of the United Nations. He called for every individual to refuse to participate in war, and called for governments to abolish weapons of mass destruction.

McDonald: But that’s only a piece of it. For some reason, I’ve been obsessed over the past couple years with how you use language to describe the totality of what surrounds us on this planet. I don’t mean the horizons. I don’t mean the northern hemisphere or the southern hemisphere, but the totality of everything that surrounds us. What language do we have for that? We don’t have a language. But we need to be able to conceive of and describe and communicate everything that exists. All religions, all thoughts, all points of view. We need to get together and make a decision: Are we going to continue doing this destructive dance that we do? Maybe we’ll decide yes. Maybe we’ll decide no. But how do we even begin?

There was once this concept that the United Nations would do that. But we used to play this game when you were a kid when you had to form a circle and you would whisper something in someone’s ear, and they’d whisper in another person’s ear and it goes around the circle and by the time it gets around, it’s a different message. Sometimes with the translations that take place at the United Nations, you wonder what the hell is going on.

During the Crimean War there was the Charge of the Light Brigade where Lucan wrote a little message to this other guy Cardigan and they misinterpreted it and they charged into heavy artillery and many were killed. Miscommunication. None of us are dealing with a full deck. I’m looking for the full deck. [laughs] Where is the full deck? Anybody got a full deck?

Spirit: Empathy is one crucial part of understanding others. On the institutional level, there is international law that applies to all nations. On the person-to-person level, there is empathy where you really begin to understand others. Like when an anti-war activist begins to understand a little about what a veteran has gone through. And that changes both of them, doesn’t it?

McDonald: Yeah! That was the fascination with me for the veterans and their families and the women in the military and the combat nurses. It’s INCLUSIVE, not exclusive.

Spirit: And when you were talking about that common language, I was thinking of John Lennon’s first line in “I Am The Walrus.” “I am he as you are he and you are me and we are all together.”

McDonald: Right! Yeah. Yeah.

Spirit: So I just solved it. You just need to listen to the Beatles more often. [both laugh]

“The Lady With the Lamp”

Spirit: In your “Tribute to Florence Nightingale”, “Lady with the Lamp” is such a beautiful song about her acts of mercy. You describe how she nurses soldiers dying thousands of miles from home. “She will hold his hand, stay with him to the end. You know she understands, she’s the soldier’s friend.”

McDonald: That’s what they called her — they called her “the soldier’s friend.” The soldiers hadn’t had a friend before. As a matter of fact, Florence Nightingale is the person who started charting. In other words, when she had a patient, she wrote their names down and what happened to them. Before her, when the war was over and the ships came back, the families stood on the dock and waited to see if their loved ones came off the ship. That was the only way they knew the fate of their loved ones. That is one of the terrible things about war. You can become missing in action. She started that whole thing of keeping records, which is a grisly task.

People would often just disappear into death, and their families would always wonder. If you were just a working-class grunt in the army, nobody knew what happened to you. Nobody ever knew. If you were upper class, one of the officers, it was different. But the lower classes are the nameless ones.

So back then, if you wanted to find out if your friend died in the war, your loved one, nobody’s keeping their records. But Florence Nightingale kept records, and that’s one reason they called her “the soldier’s friend.” Because nobody was the soldier’s friend before then.

Spirit: In your song, a dying soldier asks Nightingale to write to his mother and send a keepsake home “to those I’ll never see again.”

McDonald: She literally did that — the first time it had ever been done. Even while nursing hundreds of soldiers, she’d write to their families and send a keepsake or photo — and at her own expense.

In Search of Florence Nightingale

Spirit: Can you describe your pilgrimage to Florence Nightingale’s home in England? And what were your feelings when you visited her gravesite?

McDonald: Oh wow, it was like a fantasy. It was like a dream of mine because I had been studying her life for years, actually, and I never dreamed that I would be able to go to her burial site.

It just so happened that I made a connection with an ex-nurse and her husband who had a Nightingale Society. They go over there every year and do this commemorative Florence Nightingale thing on her birthday. I happened to be going to England at the same time for some gigs, and they took me over there to that little parish church where she’s buried.

Oh my God, it was fantastic. It was a missing piece in my journey through Florence Nightingale’s life because I had been to some other places, and that was the one place that I hadn’t been. And through them, I got to attend the commemorative ceremony that happens there every year in Westminster Abbey, too. So it was amazing, really. It was just incredible.

Spirit: You had already done a lot of research into her life. Did the trip change your picture of her life and work?

McDonald: It just really brought her life down to earth, rather than it being a fantasy in a book. I had been just looking at pictures for a number of years. I got to actually see her gravesite. I got to go into that church. I got to have a feel for what her life was actually like. We went to the main building, the main mansion, that she lived in, which is now a boys school. It was open on that day to the public.

I got to walk on the grounds that I had only seen pictures of. I got to stand under the tree where she supposedly got her call from God. All these things just had been pretty abstract to me, but I was fascinated with them, and then I got to physically be right there. It was incredible. It was also incredible that it all fell together like that on that trip. It was just in a few days that all of that stuff happened to me. And I took some pictures of it and got to put it up on my website of her life. It was amazing. You know, I’m a rabid fan of hers.

Spirit: Your “Tribute to Florence Nightingale” teaches a great deal about the destructive effects of war on soldiers. She also is one of the greatest teachers in history about the importance of compassion and care-giving.

McDonald: I don’t exactly know why I find Florence Nightingale so interesting. She recognized the dehumanizing effects of war on the warriors. She talks of the effect that war has on the soldiers, making them drink and be sadistic.

She came to tend to their physical wounds and, in that, she was different from the way the military treated them. She was caring and kind. The old soldiers accused her of “spoiling the brutes.” She tended to their last wishes and desires before death. No one had done that before. Then she noted the psychological and emotional effect war had on their personalities and decided to do something about it.

On her own dime, she built little cafes and got people to give lessons to the soldiers and provided writing materials for them to write home. And on her own, she developed a system so that they could send money home to their families. In that sense, she was the inventor of the USO with reading rooms, educational courses and savings plans.

She did this over 150 years ago. And today we live in a world of warrior worship. We don’t hate and disrespect soldiers any more, but we place them on a pedestal that dehumanizes them. So I just think it is important to examine war from every angle possible.

I do believe that war is caused by civilians, not soldiers. So anything we can do to see war from the point of view of soldiers is important, because after all, they do not exist alone like robots or projections of our minds. They are our family members and when they feel something, we feel it. When they dysfunction, we dysfunction. The cost is huge, not only in physical terms, but in emotional and spiritual terms. I think that if we open up to see it, we have no choice but to stop doing it or die. Thanks for getting me to think about all this. It is a challenge to put into words. I, of course, mostly put things into song.

Country Joe and the Fish

Spirit: Country Joe and the Fish were deeply involved in the counterculture of the Bay Area. That period is now seen in almost mythic terms as a utopian and revolutionary time. What was it like for you to be part of the so-called Aquarian Age?

McDonald: It was important for me to be part of the Aquarian Age. Up until then in my life, I had never felt a real part of something like the Aquarian Age. We were collectively something. I don’t know how to describe it, except that it was magical. It was like all at the same time, amazing stuff happened in Paris, stuff happened in London, stuff happened in San Francisco — and BOOM! Everybody agreed on the same premise: peace and love. It was a moment of peace and love. And it really happened. I don’t know how or why it happened. But it was a wonderful thing to happen. It was so great to be called a hippie! I wanted to be a hippie my whole life. And there I was — a hippie! And I’m still a hippie. Peace and love.

Spirit: In his book, The Year of the Young Rebels, Stephen Spender described the same spirit of freedom in Mexico, Paris, London, Czechoslovakia and the U.S. The spirit of peace and love was happening all over the world in 1968.

McDonald: Yeah! A friend of mine, Fito de la Parra, who plays drums with Canned Heat, grew up in Mexico. He made a documentary about the hippie peace-and-love thing in Mexico and what happened in Mexico City with these little coffeehouses. These people started rock bands and then they had their little Woodstock thing out in the country where thousands of people came. I’ve seen footage of it. And right after that, the government shut down every single radio station and club, and it took 20 years for rock and roll in Mexico to come back.

Spirit: The government saw the music as a threat.

McDonald: I don’t know why, but rock and roll is a threat to the leaders. You know, it’s illegal to have a rock band in Iran. You can’t. You’ll get arrested. We’re lucky to be in America. If I wasn’t in America, I would have been in prison or killed like Joe Hill (the IWW union activist and songwriter).

Spirit: There is a kind of lazy revisionism that mocks the 1960s counterculture. But there was a great outpouring of freedom and imagination and rebellion — an uprising of peace and love. A whole generation felt that.

McDonald: I really agree with what you’re saying. And it was accessible to everyone. It was completely democratic. Total, pure democracy. We called them hippies. Anybody could become a hippie just by being a hippie.

I could be something that I’d wanted to be my whole life. I felt free. I felt part of it all. I felt safe. I was part of something and I felt useful. I felt like I had found a niche, something that I could do. I had a talent — I could make music. I could be a part of it all. And it was fun. It was a lot of fun.

The other thing about being a hippie that was really great was that soon after it began in 1967, everyone in the mainstream began to hate hippies. And that made it even more exciting. It was a good thing to be hated by the mainstream, because we were the anti-heroes. If they hated us — all these squares and fascists and Nazis and the mainstream people that had let us all down — if they hated us just because we were having fun, then it had to be great. We could be pretend heroes, and soon, Marvel Comics began coming out with all these superheroes — the birth of Spiderman, X-Men and all that stuff.

Spirit: Long-haired and mystic heroes like Dr. Strange, Thor, Silver Surfer?

McDonald: Dr. Strange was great! He had an astral projection of his spirit. I mean, wow, how cool was that? And with LSD you could imagine having astral projection yourself. And it was fun. That was the missing element with all the other stuff in my life. It was pure, unadulterated fun.

Spirit: You had good timing in moving to Berkeley in 1965 right when the whole counterculture was about to take off.

McDonald: Being a hippie was something that I had dreamed of, because it was something I could turn myself into. I had tried a lot of things before which were not very satisfying. And being a hippie was easy to do, because you could just wear cheap clothes from the second-hand shops, or anything that you wanted.

Also, it had that peace and love vibe to it, which was free from politics, and from dogmatism and from what I considered theoretical bullshit. I hadn’t found that freedom before in all the traditional things I had explored from the military and high school and the left-wing politics from my family.

Spirit: What was it like for Country Joe and the Fish to play at the Fillmore Auditorium and the Avalon Ballroom in the glory days of psychedelic music?

McDonald: We played a lot at the Fillmore and the Avalon starting in 1967. People would do these crazy psychedelic dances. There would usually be three bands playing two sets each. So it was six sets of music during the night. And there was just one dressing room, so all the guitar cases and everything would be crammed in there. Everybody was just mingling together. There was no hierarchy of the top-billed group and the bottom of the bill, or “We’re more famous than you.”

I used to stand in front, next to the stage, right at Jerry Garcia’s feet, watching his hands really closely because he did a really neat thing when he played the guitar that I wanted to figure out. And eventually I did figure it out. It was the way he bent the guitar strings.

Spirit: Did the new music and the new counterculture make you feel like you were now part of a community?

McDonald: We were part of a community. We were just across the Bay in Berkeley, and we did find our way into San Francisco, just because the phone rang. Things happened really fast in 1966, ‘67 and ‘68 — unbelievably fast. So we became part of that community, and that was really nice because I think pretty much everybody who was a part of that community didn’t feel like they were a part of the American society.

We had been rejected in one way or another by that society, and we found this new identity as a hippie, and a lifestyle that was disdained by the establishment. And we created a music that was disdained by the establishment. Everybody brought their own unique kind of music and then they began struggling with the definition of it. Was it West Coast rock? Was it psychedelic music? What the heck was it? [laughs]

The music industry could not figure out what the hell it was. Then very quickly, they figured out that they had found a gold mine and they began signing up bands, and making albums and putting it out there. The industry wanted to make money off the music. But we never thought about money — never. Country Joe and the Fish never thought about money. The Grateful Dead probably never thought about money.

Spirit: Still, the San Francisco sound became huge and vastly influential, almost overnight.

McDonald: Oh, it exploded nationally and internationally, and it all happened on the West Coast. And most of it happened here in the San Francisco Bay Area. It was magic. It was really magic. Because you couldn’t explain why it happened. I think the Bay Area has something that allows things to happen. The Gold Rush, beatniks, the longshoremen’s union. Every now and then, something explodes in the Bay Area and then people begin coming to the Bay Area. The Steve Miller Band came to the Bay Area and the Bay Area had it all. It was fun and magic and unpretentious.

Monterey Pop Festival

Spirit: The Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967 was a peak moment for the counterculture. Country Joe and the Fish are shown playing in D.A. Pennebaker’s film, Monterey Pop. What was it like to play at Monterey?

McDonald: Well, I played at Monterey with the Fish as part of the group, but I also had my own separate experience. I wandered around and I watched a lot of the concert. I took Owsley’s new invention called STP. He was passing it out and I took a tab and a half of that and I felt like I was walking through a Monet painting the whole entire time. I remember being on the beach yelling to porpoises and having them look back at me.

I watched pretty much the whole show and I had a good time. You know, I enjoyed being part of the Aquarian Age and those incredible moments of musical history when just all that stuff was happening — like the best potluck you’ve ever attended in your life. It was unbelievable.

I was right there in the front row when Jimi Hendrix played and set his guitar on fire with some lighter fluid. I’d never seen a person do that. I also saw The Who play and they were really great, but the amazing thing was that they smashed their instruments. I couldn’t understand that because we had saved up to buy our instruments. I was a poor kid when I was growing up so I couldn’t understand why anybody would smash their instruments. Otis Redding was incredible. Oh my God, he was so good! Those are the highlights that I remember and, of course, Janis Joplin.

Spirit: I thought Janis doing “Ball and Chain” at Monterey was amazing.

McDonald: Yeah, I thought she was good. She obviously mesmerized the audience and they were just all gaga over her. It was a great show. We had been boyfriend-girlfriend for two or three months in the Haight-Ashbury before Monterey. We were breaking up at the time of Monterey. Before Monterey happened, I was there when Chet Helms introduced her at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco when she first hooked up with Big Brother and the Holding Company. I loved her with Big Brother and the Holding Company. I thought that was a great rock and roll band.

Spirit: I did too. Some critics were putting them down as excessive, but I thought Big Brother was a great band and worked well with Janis. You wrote a moving song called “Janis.” How did that song come about?

McDonald: When I broke up with Janis, she said, “Would you write a song for me before you get too far away from me?” So I was up in Vancouver and I played a little thing on my guitar and I quickly wrote the lyrics and the song, “Janis.” I liked the song.

Spirit: It’s a really pretty song. You wrote, “Into my life on waves of electrical sound and flashing light she came.”

McDonald: Yeah, people really liked the song. And I do too. I think it’s really nice.

Spirit: What was Janis like in person?

McDonald: Well, Janis was really obsessed with turning herself into Janis Joplin and she was very aggressive. She wanted to be Otis Redding. She had heard Otis and she really loved Otis Redding and she wanted to be Otis Redding. She really wanted approval. She was kind of an ordinary, down-home girl, you know, and she was very, very smart. Very aggressive and didn’t want anything to do with politics. She said, “I don’t need no-fucking-body telling me nothing, man.”

Singing for Peace at Woodstock

Spirit: Speaking of historic festivals, there’s that amazing moment at Woodstock when you were able to get hundreds of thousands to join you in singing to stop the Vietnam War. How did you end up all alone on the Woodstock stage, without the rest of the Fish, singing to that massive audience?

McDonald: By the time Country Joe and the Fish came to Woodstock, the band was pretty much falling apart. Three of the original members were gone and we had new members. Chicken Hirsh, our drummer, had just quit the band abruptly, less than two months before that. I was really not liking the band anymore.

The magic that we had in the original arrangements — the complicated, wonderful, psychedelic songs that we were playing on the first album — could not even be played by this new band. We were making money, but we were on the treadmill of a road band going out and playing gigs. I felt really estranged from the band.

But I have always loved playing outdoors and I loved these festivals. We had played the Monterey Festival and I loved watching all the other bands because I just love music and I loved this new music. So I went to Woodstock on Thursday without the band. The band came on Friday. I went out to the stage to see what was happening because I loved watching the production get going before the bands come, and then the bands setting up and playing. I love the whole gestalt of a rock show. On the second day, I was there early when Santana was supposed to go on. I was hanging around the stage just digging the scene, and Santana couldn’t get through because of the traffic.

So Bill Belmont, the guy who was our road manager, was kind of moonlighting on the production staff of Woodstock, with John Morris who was the production coordinator. They were upset because they couldn’t put Santana on as the next act. So I was sitting on the stage and John and Bill came over and said, “How would you like to start your solo career?” I said, “What the hell are you talking about?” They told me, “Just go out and play some stuff until Santana gets here.”

I didn’t really want to do it, so I told them I didn’t have a guitar. They went and found a cheap, really great Yamaha guitar, a Yamaha FG 150, and they gave it to me. I was looking for excuses then, so I said, “I don’t have a guitar strap.” So Bill Belmont cut a piece of rope off the rigging and tied it to the guitar and they pushed me out on stage.

I didn’t know what the hell to do, so I sang a couple country-western songs off my album and I sang a couple other songs from my repertoire, and nobody in the audience was paying any attention to me at all. It was like a giant family picnic out there. But I decided to do the “Fish Cheer” and “Fixin’ to Die Rag” and I started feeling a little bit excited about it.

I went up to the microphone and I just yelled, “Give me an F!” And they all stopped talking to each other and looked at me and yelled, “F!” And I thought, “Oh boy, here we go.”

So I got pretty brave because they did the whole Fish Cheer with me, and then I was singing the song, “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag.” I could see that the crowd seemed to be having a good time and they started to stand up, so I got really brave. I started haranguing them to sing louder, because if you want to stop the war you have to sing louder than that.

I went on and finished the song and they were all standing up and jumping up and down — and there you go. But I didn’t know they were making a movie of it. I didn’t even notice that.

Spirit: What did you think the first time you watched the movie and saw “Fixin’ to Die Rag” with the bouncing ball to the lyrics and a huge crowd singing and cheering along to your anti-war message?

McDonald: Well, I was delighted. You know, Michael Wadleigh, the director, had drawn upon documentary film crews to put together his film crew to shoot Woodstock in 16 millimeter. All of those crews were people who had been working on sociopolitical documentaries up to the time of Woodstock, and Michael himself had roots in sociopolitical documentaries and social movements in America.

So he really jumped onto putting in “Fixin’ to Die Rag” as being a sociopolitical statement — a contemporary statement about the Vietnam War, because generally speaking, no one was making a political statement in the film. Joan Baez talked about her husband being in jail as a draft resister, and the Richie Havens song “Freedom” seems to have overtones of being political, but really nobody was making a political statement.

So Michael Wadleigh really liked that song, and he called me about three months after the festival to go down to L.A. We sat in the projection room together, just me and him, and he showed me what you see in the Woodstock film of me singing with the bouncing ball. I couldn’t believe it. It was really cool. He said, “How do you like it?” And I said, “Whoa, that’s great.” I had no idea it would change my life.

Spirit: How did it change your life?

McDonald: When I walked off stage, John Morris said into the microphone, “That was Country Joe McDonald.” So it established me as Country Joe McDonald and that identity of making a statement about the Vietnam War. It allowed me to go on and have a solo career, and travel all over the world and make records and have bands.

It also enabled me to be somebody Vietnam veterans could look to, and in hearing that song, to cope and deal with the insanity of the Vietnam War. Because the song does not say anything bad about soldiers. It just makes a statement about the war and the social and political roots of the war and how it came to be.

Just recently, I got asked by Bob Santelli, who is the executive director of the Grammy Museum in L.A. and also worked at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland, to be a participant at a symposium on the Vietnam War in Austin, Texas. [Editor: The Vietnam War Summit will be held April 26-28 (2016) at the LBJ Presidential Library. TM]

There’s one session called “One, Two, Three: What Are We Fighting For? The soundtrack of the Vietnam War, in country and at home.” I will be there, being interviewed by Bob Santelli and singing some songs. I never dreamed that would happen.

Spirit: Singing those words — “One, two, three, what are we fighting for” — took you from a street corner in Berkeley to Woodstock and now, all the way to the Vietnam War summit at the LBJ Library.

McDonald: Well, especially because in 1965, when we made that little EP, that 7 inch record in the jug-band style of music, it had “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” on it. But it also had another song called “Superbird,” which was about Lyndon Baines Johnson. I joked with Bob and I said maybe I’ll sing “Superbird.” I think he got a little bit nervous because it has that chorus: “We’re going to send you back to Texas to work on your ranch.”

All that never, never would have happened if it hadn’t been for Woodstock. So there you go!

[NOTE: This is Part Two of a four-part interview; Part One has also been posted today. Parts Three and Four will be posted in June.]

EDITOR’S NOTE: Terry Messman is a regular contributor to this site. Please click on his byline to view his Author’s page, for an index of his interviews and articles. He is the editor and designer of Street Spirit, a street newspaper published by the American Friends Service Committee and sold by homeless vendors in Berkeley, Oakland, and Santa Cruz, California. Country Joe McDonald’s personal website is a lively source of information about him, his recordings, and books by and about him.