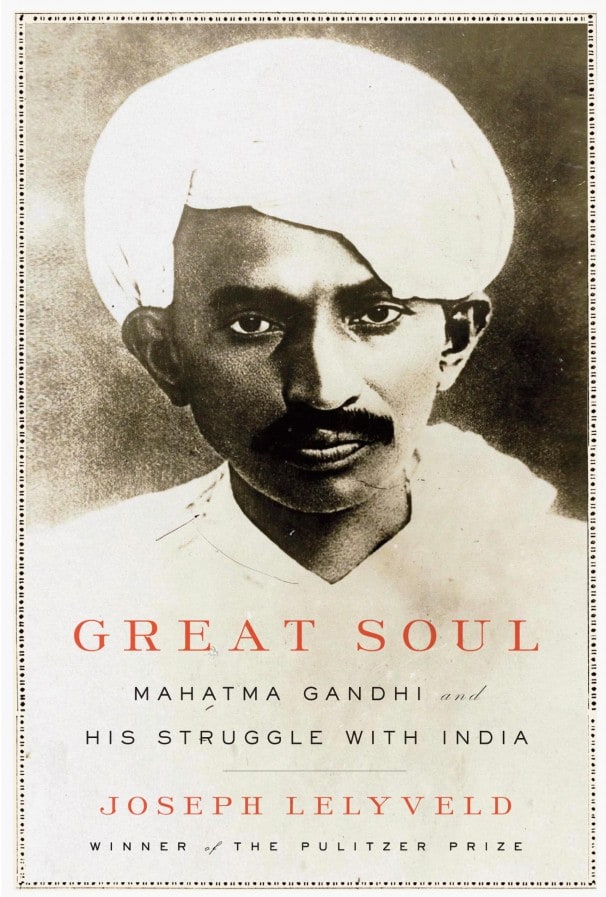

Mahatma Gandhi, Apostle of Nonviolence: An Introduction

by John Dear

Book cover illustration courtesy John Dear; johndear.org

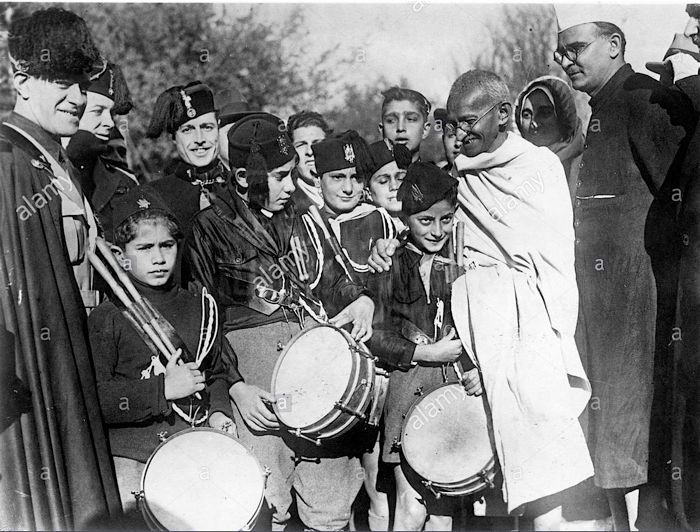

When Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated on January 30, 1948, the world hailed him as one of the greatest spiritual leaders, not just of the century, but of all time. He was ranked not just with Thoreau, Tolstoy, and St. Francis, but with Buddha, Mohammed and even Jesus. “Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth,” Albert Einstein wrote at the time.

Gandhi’s legacy includes not just the brilliantly waged struggle against institutionalized racism in South Africa, the independence movement of India, and a ground-breaking path of interreligious dialogue, but also boasts the first widespread application of nonviolence as the most powerful tool for positive social change. Gandhi’s nonviolence was not just political: It was rooted and grounded in the spiritual, which is why he exploded not just onto India’s political stage, but onto the world stage, and not just temporally, but for all times.

Gandhi was, first and foremost, a religious man in search of God. For more than fifty years, he pursued truth, proclaiming that the best way to discover truth was through the practice of active, faith-based nonviolence.

I discovered Gandhi when I was a Jesuit novice at the Jesuit novitiate in Wernersville, Pennsylvania. My friends and I were passionately interested in peace and justice issues, so we undertook a detailed study of Gandhi. We were amazed to learn that Gandhi professed fourteen vows, even as we were preparing to profess vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. I added a fourth vow—under Gandhi’s influence—a vow of nonviolence, as Gandhi had done in 1907. My friends and I undertook our own Gandhian experiments in truth and nonviolence, with prayer, discussions, fasting, and public witness, followed by serious reflection. My friends and I returned to Gandhi as a way to understand how best to respond to our own culture of violence.