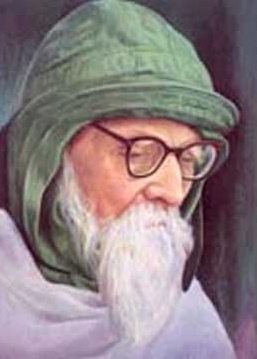

The King of Kindness: Vinoba Bhave and His Nonviolent Revolution

by Mark Shepard

Once India gained its independence, that nation’s leaders did not take long to abandon Mahatma Gandhi’s principles. Nonviolence gave way to the use of India’s armed forces. Perhaps even worse, the new leaders discarded Gandhi’s vision of a decentralized society, a society based on autonomous, self-reliant villages. These leaders spurred a rush toward a strong central government and a Western-style industrial economy. But not all abandoned Gandhi’s vision. Many of his “constructive workers”, development experts and community organizers working in a host of agencies set up by Gandhi himself, resolved to continue his mission of transforming Indian society. And leading them was a disciple of Gandhi previously little known to the Indian public, yet eventually regarded as Gandhi’s “spiritual successor”, Vinoba Bhave, a saintly, reserved, austere man most called simply Vinoba. How did he assume this status?

In 1916, at the age of 20, Vinoba was in the holy city of Benares trying to come to a decision about his life. Should he go to the Himalayas and become a religious hermit? Or should he go to West Bengal and join the guerillas fighting the British? Then Vinoba came across a newspaper account of a speech by Gandhi. He was thrilled, and soon after joined Gandhi in his ashram. Gandhi’s ashrams were not only religious communities, but also centers of political and social action. As Vinoba later said, he found in Gandhi the peace of the Himalayas united with the revolutionary fervor of Bengal.

Gandhi greatly admired Vinoba, commenting that Vinoba understood Gandhian thought better than he himself did. In 1940 he showed his regard by choosing Vinoba over Nehru to lead a national protest campaign against British war policies. After Gandhi’s assassination on January 30, 1948, many of Gandhi’s followers looked to Vinoba for direction. Vinoba advised that, now that India had reached its goal of swaraj—independence, or self-rule—the Gandhians’ new goal should be a society dedicated to sarvodaya, the “welfare of all.” The name stuck, and the movement of the Gandhians became known as the Sarvodaya Movement. A merger of constructive work agencies produced Sarva Seva Sangh—“The Society for the Service of All”—which became the core of the Sarvodaya Movement, as the main Gandhian organization working for broad social change along Gandhian lines.

Vinoba had no desire to be a leader, preferring a secluded ashram life. This preference, though, was overturned by events in 1951, following the yearly Sarvodaya conference in what is now the central Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. At the close of that conference, Vinoba announced his intention to journey through the nearby district of Telengana.

He couldn’t have picked a more troubled spot.

Telengana was at that moment the scene of an armed insurrection. Communist students and some of the poorest villagers had united in a guerilla army. This army had tried to break the land monopoly of the rich landlords by driving them out or killing them and distributing their land. At the height of the revolt, the guerrillas had controlled an area of 3,000 villages. But the Indian army had been sent in, and began a campaign of terror. Villages were occupied by government troops during the day and by Communists at night. Each side would kill those they suspected of supporting the other side and so most lived in terror of either side.

Vinoba hoped to find a solution to the conflict and to the injustices that had not only spawned it but also that it had spawned. Refusing a police escort, he and a small company set off on foot. On the third day of his walk, Vinoba stopped in the village of Pochampalli, which had been an important Communist stronghold. Setting himself up in the courtyard of a Muslim prayer compound, he was soon receiving visitors from all the factions in the village, among which was a group of 40 families of landless Harijans. (Harijan or Untouchables means literally “child of God.”) The Harijans told Vinoba they had no choice but to support the Communists, because only the Communists would give them land, and asked if Vinoba would ask the government instead to give them land. Vinoba replied, “What use is government help until we can help ourselves?” But he himself wasn’t satisfied by the answer. He was deeply perplexed.

Late that afternoon, by a lake next to the village, Vinoba held a prayer meeting that drew thousands of villagers from the surrounding area. Near the beginning of the meeting, he presented the Harijan’s question to the assembly. Without really expecting a response, he said, “Brothers, is there anyone among you who can help these Harijans find land?” A prominent farmer of the village stood up. “Sir, I am ready to give one hundred acres.” Vinoba could not believe his ears. Here, in the midst of a civil war over land monopoly, was a farmer willing to part with 100 acres out of simple generosity. And Vinoba was just as astounded when the Harijans declared that they needed only 80 acres and wouldn’t accept more!

Vinoba suddenly saw a solution to the region’s turmoil. In fact, the incident seemed to him a sign from God. At the close of the prayer meeting, he announced that he would walk all through the region to collect gifts of land for the landless.

So began the movement called Bhoodan, or “land-gift”. Over the next seven weeks, Vinoba asked for donations of land for the landless in 200 villages of Telengana in south central India. Calculating the amount of India’s farmland needed to supply India’s landless poor, he would tell the farmers and landlords in each village, “I am your fifth son. Give me my equal share of land.” And in each village—to his continued amazement—the donations poured in.

Who gave, and why? At first most of the donors were farmers of moderate means, including some who themselves owned only an acre or two. To them, Vinoba was a holy man, a saint, the Mahatma’s own son, who had come to give them God’s message of kinship with their poorer neighbors. Vinoba’s prayer meetings at times took on an almost evangelical fervor. As for Vinoba, he accepted gifts from even the poorest—though he sometimes returned these gifts to the donors—because his goal was as much to open hearts as to redistribute land.

Gradually, though, the richer landowners also began to give. Of course, many of their gifts were inspired by fear of the Communists and hopes of buying off the poor—as the Communists were quick to proclaim. But not all the motives of the rich landowners were economic. Many of the rich hoped to gain “spiritual merit” through their gifts, or at least uphold their prestige. After all, if poor farmers were willing to give sizeable portions of their land to Vinoba, could the rich be seen to do less? And perhaps a few of the rich were even truly touched by Vinoba’s message. As Vinoba’s tour gained momentum, even the announced approach of the “god who gives away land” was enough to prepare the landlords to part with some of their acreage.

Soon Vinoba was collecting hundreds of acres a day. What’s more, wherever Vinoba moved, he began to dispel the climate of tension and fear that had plagued the region. In places where people had been afraid to assemble, thousands gathered to hear him—including the Communists. At the end of seven weeks, Vinoba had collected over 12,000 acres. After he left, Sarvodaya workers continuing to collect land in his name received another 100,000 acres. The Telengana march became the launching point for a nationwide campaign that Vinoba hoped would eliminate the greatest single cause of India’s poverty: land monopoly. He hoped as well that it might be the lever needed to start a “nonviolent revolution”—a complete transformation of Indian society by peaceful means. The root of oppression, he reasoned, is greed. If people could be led to overcome their possessiveness, a climate would be created in which social division and exploitation could be eliminated. As he later put it, “We do not aim at doing mere acts of kindness, but at creating a Kingdom of Kindness.”

Soon Vinoba and his colleagues were collecting 1,000 acres a day, then 2000 and 3000. Several hundred small teams of Sarvodaya workers and volunteers began trekking from village to village, all over India, collecting land in Vinoba’s name. Vinoba himself—despite advanced age and poor health—marched continually, touring one state after another.

The pattern of Vinoba’s day was always the same. Vinoba and his company would rise by 3:00 a.m. and hold a prayer meeting for themselves. Then they would walk ten or twelve miles to the next village, Vinoba leading at a pace that left the others struggling breathlessly behind. With him were always a few close assistants, a bevy of young, idealistic volunteers, teenagers and young adults, male and some female, mostly from towns or cities, plus some regular Sarvodaya workers, a landlord, a politician, or an interested Westerner.

At the host village a brass band would usually greet them, a makeshift archway, garlands, formal welcomes by village leaders, and shouts of “Sant Vinoba, Sant Vinoba!” (“Saint Vinoba!”) After breakfast, the Bhoodan workers would fan out through the village, meeting the villagers, distributing literature, and taking pledges. Vinoba himself would be settled apart, meeting with visitors, reading newspapers, answering letters. In late afternoon, there would be a prayer meeting, attended by hundreds or thousands of villagers from the area. After a period of reciting and chanting, Vinoba would speak to the crowd in his quiet, high-pitched voice. His talk would be completely improvised, full of rich images drawn from Hindu scripture or everyday life, exhorting the villagers to lives of love, kinship, sharing. At the close of the meeting, more pledges would be taken.

There were no free weekends on this itinerary, no holidays, no days off. The man who led this relentless crusade was 57 years old, suffered from chronic dysentery, chronic malaria, and an intestinal ulcer, who restricted himself, because of his ulcer, to a diet of honey, milk, and yogurt. As the campaign gained momentum, friends and detractors alike watched in fascination. In the West, too, Vinoba’s effort drew attention. In the United States, major articles on Vinoba appeared in the New York Times, the New Yorker—Vinoba even appeared on the cover of Time.

By 1954, the Gandhian Sarvodaya campaign had collected over 3 million acres, the total eventually reaching over 4 million. Much of this land turned out to be useless, and in many cases landowners reneged on their pledges. Still, the Gandhians were able to distribute over 1 million acres to India’s landless poor, far more than had been managed by the land reform programs of India’s government. About half a million families benefited.

Meanwhile, Vinoba was shifting his efforts to a new, higher gear. After 1954, Vinoba began asking for “donations” not so much of land but of whole villages. He named this new program Gramdan—“village-gift.” Gramdan was a far more radical program than the Bhoodan land-gift. In a Gramdan village, the village collectively owned the land and parceled it out to individual families according to need. Because the families could not themselves sell, rent, or mortgage the land, they could not be pressured off it during hard times, as normally happens when land reform programs bestow land title on poor individuals.

Village affairs were to be managed by a village council made up of all adult members of the village; the council could not adopt any decision until everyone accepted it. This was meant to ensure cooperation and make it much harder for one person or group to benefit at the expense of others.

While Bhoodan had been meant to prepare people for a nonviolent revolution, Vinoba saw Gramdan as the revolution itself. Like Gandhi, he believed that the divisiveness of Indian society was a root cause of its degradation and stagnation. Before the villagers could begin to improve their lot, they needed to learn to work together. Gramdan, he felt, with its common land ownership and cooperative decision-making, could bring about the needed unity. Once this was achieved, the “people’s power” it would release would make anything possible.

Vinoba’s Gramdan efforts progressed slowly until 1965, when an easing of Gramdan’s requirements accelerated the campaign. By 1970, the official figure for Gramdan villages was 160,000, that is, almost one-third of all India’s villages. It turned out, however, that it was easier to get a declaration of Gramdan than to set it up in practice. By early 1970, only a few thousand villages had transferred land title to a village council. In most of these, progress was at a standstill. What’s more, most of these few thousand villages were small, single-caste, or tribal—not your average Indian village. And, by 1971, Gramdan as a movement had collapsed under its own weight.

The Gramdan movement did leave behind more than a hundred Gramdan “pockets”, some made up of hundreds of villages—where Gandhian workers settled in for long-term development efforts. These pockets were to form the base of India’s Gandhian movement, in which Gandhians could help some of India’s poorest by organizing Gandhian-style community development and nonviolent action campaigns against injustice.

Vinoba returned to his ashram for the final time in June 1970, after thirteen years of continual marching. During his final years, he continued to inspire new programs—for instance, Women’s Power Awakening, a Gandhian version of women’s liberation. He also launched an ongoing campaign to try to halt the butchering of useful farm animals, a practice destructive of India’s traditional agriculture.

Vinoba died on November 15, 1982. In his dying, as in his living, he was deliberate, instructive, and, in a way, lighthearted. After suffering a heart attack, Vinoba decided to “leave his body before his body left him.” He therefore simply stopped eating until his body released him.

Further Reading: (MS)

Vinoba Bhave, Vinoba on Gandhi, Benares: Sarva Seva Sangh, 1973. Selected talks. Clear, lucid, and sometimes controversial.

Vinoba Bhave, Democratic Values, Benares: Sarva Seva Sangh, 1964. Selected talks on his social philosophy.

Erica Linton, Fragments of a Vision: A Journey through India’s Gramdan Villages, Benares: Sarva Seva Sangh, 1971. By a visiting Englishwoman. An inspiration for my own book.

Sriman Narayan, Vinoba: His Life and Work, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, Bombay, 1970.

Geoffrey Ostergaard & J. P. Amrit Kosh Nonviolent Revolution in India, New Delhi: Sevagram, and Gandhi Peace Foundation, 1985. An extensive scholarly treatment of the Gandhians after Gandhi though slanted more toward Jayaprakash Narayan.

Mark Shepard, Gandhi Today: A Report on Mahatma Gandhi’s Successors, Arcata, California: Simple Productions, 1987 (reprinted by Seven Locks Press, Washington, D.C., 1987). Includes the more complete account from which this article is drawn.

Mark Shepard, Since Gandhi: India’s Sarvodaya Movement, Weare, New Hampshire: Greenleaf Books, 1984. Booklet, mimeographed. An earlier, more detailed, more critical account—with much unauthorized editing. Also lists additional sources. Available only from Greenleaf Books.

Vishwanath Tandon (ed.) Selections from Vinoba, Benares: Sarva Seva Sangh, 1981.

Vishwanath Tandon, Acharya Vinoba Bhave, New Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, 1992. (Acharya is a title of respect meaning “spiritual teacher.”)

Hallam Tennyson, India’s Walking Saint: The Story of Vinoba Bhave, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1955. A first-hand account by a visiting American Quaker.

Lanza del Vasto, Gandhi to Vinoba: The New Pilgrimage, New York: Schocken, 1974. Biography, plus a journal of a Bhoodan tour. By a prominent European Gandhian and the founder of the Community of the Ark.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Mark Shepard describes himself as having been among other things “a journalist specializing in Mahatma Gandhi, the Gandhi movement, nonviolence, peacemaking, simple living, and utopian societies; a musician on flute, drums, and other instruments; and a would-be professional poet”. He is the author of Gandhi Today; Mahatma Gandhi and his Myths, and The Community of the Ark, besides which he is also the author of children’s books. His website can be consulted for excerpts from his books and further biographical information. For more information about L’Arche, the English language version of their site is at this link. But L’Arche’s French site has more information than the English about the original community and can be found here.