Nonviolent Peace Training as a Means of Linking Research and Action

by George Lakey

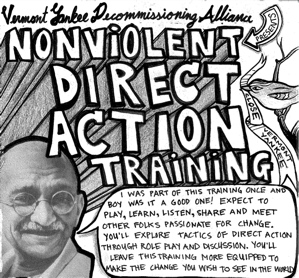

Poster art courtesy wrongkindofgreen.org

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished essay was a paper presented at the International Conference of Peace Researchers and Peace Activists (Noordwijkerhout, Netherlands, July 1-6 1975), and is another in our series of important discoveries from the War Resisters’ International archive. Please see the notes at the end for archival information, and for a note about George Lakey. JG

Training for peace action is a fairly new phenomenon. By training I mean the systematic sharing of skills and knowledge. Activists in former years could learn by apprenticing themselves to experienced leaders, or could pay special attention to those conferences and institutes featuring nonviolent organizers. But there was nowhere they could go to get systematic, long-term training.

The burst of nonviolent action in the nineteen-sixties stimulated people in a number of countries to seek to remedy this. In 1965 the first international conference on training for nonviolent action was held in Perugia, Italy, by War Resisters’ International. Activists came from as far away as India and the U.S. to compare notes on training experience.

One stimulus in the U.S. was the civil rights movement in the South, where the shootings and beatings helped activists realize that experience can be a very expensive teacher, and that it pays to learn from the experience of others as well as our own.

Another stimulus to long-term training programs in the U.S. was the growing anti-war movement, which increased along with the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. The establishment of the Peace Corps by President Kennedy, its equivalent inside the U.S. known as VISTA, and the so-called war against poverty declared by President Johnson, all contributed. But the U.S. lacked a training center where people could learn organizing skills and knowledge with a nonviolent orientation.

In 1965 the Martin Luther King, Jr., School of Social Change was created in Chester, Pennsylvania, to answer this need. It was a graduate school with about two-dozen students and a faculty of five the first year, including myself. Although administrated by Crozer Theological Seminary, the King School was secular in spirit. After three years it was accredited to give an M.A. degree in Social Change.

From the beginning the King School recruited students interested in peace as well as domestic issues such as racism and poverty. That choice influenced the character of the school, because the intermeshing of a variety of issues pushed us all to develop a broader understanding of the structures of violence which underlay the various social problems.

From the beginning too, we tried to connect field training with theory. The Quaker pacifist, economist and philosopher Kenneth Boulding was one of our first guest lecturers, and there was a stream of visiting scholars as well as activists who shared their perspectives. Each student worked with an agency — often a movement group — and seminars were held in which people tried to join theory and practice. There was also some training in basic sociological tools of action research, partly to help students become more rigorous in finding out the parameters of their situation, and partly to help them become consumers of research on peace and social problems.

The five years of the King School were exciting and in many ways productive, and the experiment ended only when the parent institution, Crozer, merged with another seminary. In my opinion (and that of several other faculty members and a number of students), however, the King School failed to realize our hopes for it. The chief failing (for the purposes of our discussion here) was that not nearly as much intellectual learning happened as we’d hoped.

There were a number of reasons for that, but two stand out in my mind. One was that the graduate school setting itself, with its hierarchical order and its homage to the forms of academia, stood in the way of learning. The school structure so frequently reminded students of the Old Order which they were rebelling against, that it was hard not to be distracted. The egalitarian values and simplicity of spirit, which often brought the students into the peace and social change movements, were contradicted by the King School as an institution, and the contradiction impeded communication and hindered learning.

The second major reason was related to the first: there was little support for the changes which students were expected to make. Change usually is risky, and we usually need support in order to take risks. The King School was highly individualistic; interaction was too often a slice of the teacher meeting a slice of the student rather than whole people becoming sisters and brothers. Since real learning means change, the lack of support for change resulted in substantial loss of learning opportunities.

Reflection and Action

A basic tension exists between the learner (researcher) and the activist in the psychological strategies employed: to learn, one maximizes uncertainty, whereas to act, one minimizes uncertainty.

To overcome this contradiction requires considerable personal growth. These strategies may have started as ways of coping with past hurts. The distress we still carry around from past hurts prevents the resolution of the tension. Fear of conflict, shyness, low estimates of self-worth can add up to avoidance of action, so that researchers turn their uncertainties to intellectual account and try to learn more about the world. Fear of authority, anxiety about integrity, fear of the absence of love can result in compulsive action, which leaves little room for ambiguities or questions. Lack of self-confidence on both sides reduces communication between activists and researchers, making them defensive about the choices they’ve made.

The King School students were caught in this tension, as I was and other people I know. The weakest part of the King School curriculum was probably the integration of theory and practice; students and faculty alike complained about the difficulties of translating one into the other. What we did not do was to put our own personal growth on the collective agenda.

An Alternative Model: The Philadelphia Life Center

In 1971 we started a new approach, which has provided a community of support for the practical application of theory: the Philadelphia Life Center. Two of the founders of the Life Center had been professors at the King School (George Willoughby and myself). The need for training seemed to us even more imperative than ever, and we were determined not to repeat our old mistakes.

The Life Center is a community for action, learning, and personal growth. Its commitment is to fundamental social change through nonviolent means. At the moment it consists of fifteen communal households clustered together in a working class/middle class neighborhood in the city of Philadelphia. Over a hundred people are involved, from three other continents as well as around the U.S. Many have come because it is a training center, and intend to go back to their homes when they have gained more strength and skill.

The structure of the community is decentralist and egalitarian. Nearly all decisions are made in household units (about issues of living together) or in working collectives. The few Life Center-wide decisions are made by consensus in plenary sessions. Some volunteers compose the executive committee, which oversees the community-owned property (most property is owned by the household units).

Life Center members start from the assumption that we were brought up to be individualistic rather than cooperative, and therefore need to pay conscious attention to the collective process. Normally, meetings close with an evaluation of this process, with attention paid to possible masculine dominance, among other things.

There is, of course, pain involved in the struggles to change. A major purpose of community is to give support at the hardest times. Since everyone is in the throes of change on one of their frontiers, people learn the skills of giving support. This is especially important for men, who traditionally have left nurturance to women; at the moment there are three men’s groups where men are learning to support each other while giving up sexist behavior patterns. Peer counseling techniques, workshops in which personal growth issues are thought about and felt, and (for some) meditation and worship are some of the conscious ways Life Center members prepare ourselves for the long struggle for peace.

The typical mode of intellectual learning is the study group. Life Center members (who already may interact through folk dancing, playing with children, or cooking, demonstrating, counseling) start study groups to learn cooperatively about theory. The most popular subject is economics, since members are often poorly grounded in that area and need the group support to tackle it. A cooperative study process called “macro-analysis seminars” was invented at the Life Center and has been used by hundreds of groups in the U.S., and is now starting in Britain. Additionally, visitors to the Life Center often share their latest thinking; in that way we learn from E.F. Schumacher, Elise Boulding, Gene Sharp, and others.

The first action by Life Center people was blockading the ports of Baltimore and Philadelphia to prevent weapons from being shipped to Pakistan during the war against Bangladesh. By means of small craft and picket lines, longshoremen were persuaded not to load weapons. The same collective led Life Center people and others in a blockade on the New Jersey coast of weapons bound for Indochina. Unlike the Pakistan action, weapons were not actually prevented from departing on Navy ships. However, the direct action on the water and on land (sit-downs on the railroad tracks) encouraged U.S. sailors to defect and added publicity to the anti-war movement.

Through these and other campaigns (just now a campaign on the Namibia issue is being developed) Life Center people get ample chance to test theory by action, and to evaluate action by theory. Alternative institutions (e.g. a cooperative printing workshop) are also being developed. The values of the Life Center are such that the members who write books feel strong pressure to participate in campaigns, and the initiators of action feel strong pressures to do intellectual work. Just as important as the pressures, however, are the supports, which enable them to do what is scarcest for them — whatever that may be.

A Community of Scholar/Activists

The Philadelphia Life Center is a very young institution, still with many gaps and problems. However, its influence and that of the network it is part of — the Movement for a New Society — have grown quickly. That may be partly because it offers a very unusual synthesis in American life. Traditionally, citadels of learning are separate from areas of action. We see the gap bridged at the upper levels of social power, where “think tanks” serve the elites. What we are not used to is seeing the gap bridged at the lower levels of power. Whether the Life Center will fully become a community of scholar/activists, or activist/scholars, I cannot yet say, but after three years I can affirm its importance to me as one person who cares about reflection and action.

Reference: IISG/WRI Archive Box 72: Folder 2, Subfolder 1. We are grateful to WRI/London and their director Christine Schweitzer for their cooperation in our WRI project.

EDITOR’S NOTE: George Lakey is director of Training for Change and editor of the invaluable website Global Nonviolent Action Database. He has taught peace studies at Swarthmore College, Temple University, and the University of Pennsylvania, and was co-founder of Jobs with Peace Campaign, director of the Quaker Action Group and founder of Men Against Patriarchy. He has been the recipient of the Ashley Montague Peace Award, and has published six influential books and countless articles. Among his works are: Strategy for a Living Revolution , Exploring Nonviolent Action, and Strategy for Non-Violent Revolution. The website of Training for Change gives a more extensive biography and bibliography.