Book Review: Dark Hope: Working for Peace in Israel and Palestine by David Shulman

1. The Activist Author

Around a decade ago I would see American news programs showing ambulances at a scene of broken glass and chaos, caused by a Palestinian suicide bomber targeting Israeli civilians. Those scenes made me wonder what life must be like for ordinary Palestinians and sympathetic pacifists among the Israelis.

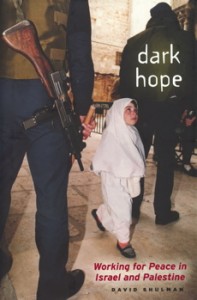

Dark Hope (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007) is a poignant book about Israeli activists’ outreach efforts to befriend and support Palestinians whose homes and fields had been impinged upon by settlers and security measures. The author belongs to a voluntary group named Ta’ayush, Arab-Jewish Partnership, formed in 2000. This alliance is “dedicated to the pursuit of peace, to ending the occupation, and to civic equality within Israel proper.” (p.1) Israeli members of Ta’ayush go out of their comfort zones to publicly take a stand to support endangered Palestinian villagers.

Of course, Ta’ayush is not alone in this work. There are similar Israeli groups, such as Rabbis for Human Rights, The Israel Committee Against House Demolitions, Bar Shalom, Gush Shalom, Kids4Peace, etc. Shulman writes of Ta’ayush: “We follow the classical tradition of civil disobedience in the footsteps of Gandhi, Thoreau, Martin Luther King.” He says the goal is “to construct a true Arab-Jewish partnership” and he quotes Ta’ayush literature: “A future of equality, justice, and peace begins today, between us, through concrete, daily actions of solidarity to end the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories and to achieve full civil equality for all Israeli citizens.” (p. 11)

The author, David Shulman is a distinguished scholar and translator. He is a poet who writes his verses in Hebrew, and an insightful writer on cultures, and he notes that politics is not his métier. (p. 4) He grew up in Iowa, migrated to Israel as a youth, and served in the Israeli army and reserves. For years he has been a tenured professor in the Comparative Religion Department at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. In his academic work he studies and translates the literature of South India, and occasionally some of the imagery and ideas of that culture are part of the discussion in Dark Hope, shedding reflected light on Israeli/Palestinian matters.

“I have… a profound feeling that the conflict raging in this tormented country is not a zero-sum game in which only one side can win,” Shulman writes. “The transparent truth is that either both sides win or both sides lose.” (p. 9) Shulman supports “a negotiated two-state solution, with Israel’s permanent borders established more or less along the pre-1967 Green Line, with suitable security arrangements for both parties… in this I apparently belong with the overwhelming majority of people on both sides of the conflict.” (p. 9) Shulman’s experiences with the Palestinians seem full of positive good will, friendship and sharing, but the problems bringing them together do not constitute a simple matter. Shulman is well aware of this.

“Political activism… is riddled with the ambiguous. Hence the fanaticism that sometimes characterizes die-hard activists. It is not easy to contain the nagging sense that dependably arises from this kind of work, that we are reducing complexity to some kind of manageable, operative slice of reality; that our ideas and plans impinge, at best, rather obliquely on that reality; and that tremendous displacements and surreal reconfigurations are taking place at every moment. Everyone brings his or her own world to politics and we inevitably project our own cosmology onto the shadowy externalities with which we are engaged. Some choices are unconscious. We all have a tendency to polarize, making our declared opponents the embodiment of dark forces and our chosen friends the messengers of light. Sometimes we may end up doing more harm than good. We read the world as best we can, and we are often wrong.” (p. 12) To be engaged is to be humbled. So be it, Shulman seems to say—it is better to do what one can than to do nothing at all.

2. The Book’s Structure

The form of the book is like an extended log, with dated entries of specific activities on a calendar of activism. But it is not strictly in chronological order. There are developing themes which allow Shulman to cluster some entries in sequences that are out of chronological order. The form works well, telling a soulful human story, and yet fixing the shifting sands of time with exact dates, as we follow him through a variety of experiences of nonviolent protest and nonviolent civil resistance.

Shulman calls these reflections “notes” about his own “small slice of reality in Israel and the occupied territories in the unhappy years 2002-2006”, a time during which he “went to demonstrations, wrote letters to the minister of defense and chief prosecutor of the army and the prime minister, went on convoys bringing food and medical supplies to Palestinian villages; was beaten up by settlers” (p.1) besides carrying on his usual academic work of teaching and research, and family activities. Most of his activist work is reminiscent of Satyagraha civil resistance work – non-violent actions of conscience reaching out to victims of injustice, trying to right social wrongs.

Dark Hope is a very rich narrative full of life experiences, hard-won insights and troubling issues. It is a documentary drama of incidents in a long struggle for humane treatment of Palestinians, and the striving of concerned activists to fulfill Israel’s highest aspirations. There are too many clichés and one-dimensional views of Israelis in the world—it seems common for many around the world to see all Israelis as the same. This heartfelt document presents much-needed nuances.

3. Satyagraha (nonviolent conscientious) Activities

The reader of the author’s narrative accompanies Shulman as he goes with a caravan of volunteers in 2002 to distribute blankets to displaced Palestinians who have been living in caves. Along the way the activists encounter a blockade of settlers’ vehicles. Shulman asks the questions that occur to a person of conscience as he walks on beyond the blockade to reach his goal: “I wonder, as I walk, whether there are soldiers there who see the whole lunatic scenario—this struggling army of blanket holders stumbling through the mud over the hills—and for a moment, at least, see through the veil: see the misery, the occupation, the human evil, the coercion and cruelty, the pointlessness, the falseness, our own deep and enduring foolishness. Is there one of them who would resist an order to demolish an innocent Palestinian’s home? Does what we are doing have any meaning? Evil is rampant on both sides of this conflict, and perhaps we are caught up in a gesture of quixotic futility. What difference does it make? On the other hand, surely one must act from this point, only this point, which is the steady, recurrent, dependable matrix, a place of utmost ambiguity. There is work to be done within, though, and beyond the confusion; because of the confusion.” (pp. 21-22) Shulman’s honesty is refreshing.

After overcoming various hurdles, Shulman writes of the moment of tossing a blanket into a container in a Palestinian’s tractor, and then going to join the villagers, and the embraces of friendship, the sharing of tea, the words of thanks spoken, and expressions of tired people hopeful for peace. Shulman goes into one of the caves where people have lived for many years. Generations of the particular Palestinian family he visited had been there since the 1830s. (p. 22) The mother of the family says, “Even if you offer me a villa in Paris, I want to live here in my home. This cave is where we were born and where we grew up. We prefer to die here rather than leave our land.” (pp. 22-3) Be it ever so humble, home is home.

Musings on being with villagers whom he helps harvest grain follow. He describes taking part in the wheat and barley harvest. This means walking bent over, using an old style sickle. With the harvests of wheat and olives he describes, there are constraints in time, and so the Palestinians need help to ensure they can gather up the food they have toiled to grow to ripeness. (pp. 24-5) It is a world of dry earth, goats and sheep, dependent on rain-fed wells for water, rather remote from the modern world. Shulman notes how it is like village life everywhere, including India, with rhythms of seasonal cycles and changes of nature. (p. 26) With each experience of reaching out, there are rewarding moments of friendship and gratitude, as well as episodes of discomfort, risk and danger.

Shulman shows the emotional toll of this work, glimpses of frustrations of activists angry at forces which uproot people living close to the land, and the feelings of those mistreated by settlers and security forces, their hurt and anger. At home again after one mission, Shulman experiences a rare sense of fury: “What we are fighting in the South Hebron Hills is pure, rarefied, unadulterated, unreasoning, uncontainable human evil. Nothing but malice drives this campaign to uproot the few thousand cave dwellers with their babies and lambs.” The vulnerable ones are powerless in their poverty, peaceful, terrified by hostility, and not a security threat. Shulman wonders what drives people to become violent and cruel to them. (pp. 27-8)

While in Twaneth in the South Hebron Hills (“something between a village and another set of caves”) to help at the time of plowing and sowing, Shulman hears gunshots in the distance. Settlers have been terrorizing farmers here with guns for weeks, but now the activists, including Shulman, hear bullets whizzing through the air close by, as barley seeds are being sown in the fields. This is a 2003 incident. Suddenly, shots are fired from the settlers nearby. “These young men have found a way and a reason, to unleash their hatred without check or restraint”—screaming, the youths rush down the hill, throwing rocks with slings and shooting guns, and some protestors are assaulted and hurt. The settlers, mostly in their twenties, yell: “You should be ashamed…What kind of Jews are you?” And Shulman yells back, “I am a Jew. That’s why I am here.” And he gets knocked down and beaten. (p. 32)

Helping in a time of plowing, giving a tree to a farmer, excavating a home which has been buried by Israeli bulldozers (p. 49), and going to collect and safely remove poison that has been left by settlers on the Palestinians’ land, are other examples of the projects the members of Ta’ayush are engaged in. The poison pellets were placed at various spots to kill herds of goats and sheep. Wild animals—such as deer and weasels—were also poisoned. Shulman and others found and gathered the pellets, putting them in sacks for disposal. (pp. 53-56) Their activities show that there are some Israelis who care deeply about the plight of the Palestinians.

When actions are taken by the Israeli government in attempts to protect the lives of Israelis from suicide bombers and other terrorists, such as the erection of a wall, which prevents Palestinian farmers from getting to their fields, there are some Israelis who refuse to accept or keep quiet about it. At the time of the wall’s erection, suicide bombs and other hostilities had killed 500 Israelis. The “refuseniks,” refusing to agree to go along with injustices which were the side-effects of the protective wall, give voice to feelings of opposition shared by many silent Israelis too. The wall made it difficult for Palestinians to tend their fields, and also made it easier for the settlers to occupy land, which belongs to Palestinians. Hearing an articulate spokesmen for the refuseniks, Shulman reflects on that basic power of taking a stand against injustice: “To be able to say no defines the human being. That and a talent for empathic imagination—so strangely rare among us. Perhaps it is because imagination is so active a mode, the first antidote to passivity. Violence corrupts precisely because of its subtle mutedness, its way of happening somewhere else, around the corner, out of sight, in Ramallah, in Jenin.” (p.131) The corruption he refers to is the taint of numbness and indifference.

In the bleakness of the Palestinians’ plight there are sometimes “stabs of hope”. (p. 137) The Hebrew word Tzedek means justice, and it is this ancient value which the refuseniks refuse to forget, whether going to harvest olives, lending a hand in house building, or protesting the wall, or dismantling barricades, or participating in programs at Hebrew University involving public speakers on controversial topics. In reality, nothing is cut and dried, black and white. Shulman does not shy away from reflecting on the nuances—there are some in the army who do not want Palestinians treated badly, and they themselves sometimes protest official policies, for example. The settlers and the army, security forces and policemen are a constant presence. The fauna and flora of Israel play their parts, as do stun grenades, tear gas and rubber bullets.

The hostility from the settlers is always dismaying. This includes throwing stones, shooting, physically attacking and breaking a video camera recording their illegal activities. The settlers harass, beat, poison, and shoot seemingly without restraint. What are the resources in Judaism to insist on treating Palestinians humanely? Shulman eloquently brings them up. The symbolic attempts to give support are signs of Israelis loyal to deep traditional values. The “dark hope” is that using intelligence, cooperation and good will can succeed where violence fails.

Sometimes all the efforts (which for a busy professor and family man must not be easy) seem like a drop in the bucket. Other times acts of civil disobedience bring violent repercussions, as when protestors work to remove a barricade, using pick-axes to remove a roadblock mound and police on horseback charge with clubs. (pp. 70-1) Sometimes Shulman is among the roughed-up, and sometimes he bandages the ones who are hurt. (p. 47) There are moments of satisfaction, when perseverance rewards the activists with experiences of connecting with other human beings, building bonds of friendship. Other times one is reminded of seemingly never-ending conflicts in places like Kashmir.

Refusing to go along with oppression and reaching out to the underdog means breaking the law sometimes. Shulman notes that Augustine wrote, “An unjust law is no law.” The logic is that when injustice appears, civil disobedience may be necessary. The idea is something like Tagore’s statement, “Poets obey higher laws than the ones they break.” Gandhi is quoted as saying it is unmanly to obey laws that are unjust—and that as long as men obey unjust laws slavery will exist. (p. 139) Gandhi also said, “There is a higher court than courts of justice and that is the court of conscience. It supersedes all other courts.”

Shulman writes, “I know this from long experience: just at the point where you yearn for some Gandhian voice—for someone to say, ‘On no account is killing justified, not for any goal on earth; violence is the wrong path’—at that point you hear chanted war cries of youth, ‘in blood and spirit’ vows of forced victory. These teenagers are not Gandhians, not now, not ever”. (p. 106) This, Shulman notes, is the worst-case scenario—16 year olds with machine guns making rash decisions. But he shows understanding and compassion for all, whether they share non-violent philosophy or not. The narrative does not get caught in a trap of one-sidedness.

Often there is a Kafkaesque sense of taking part in an absurd drama of denied rights. For example there is a Supreme Court scene, which involves authorities in Israel sitting in judgment over land which was not in Israel. “A few days ago I stood in the caves; I worked in the field; I held a baby goat and spoke with the young mothers. Only a madman could consider judging these people’s right to be at home: it is like appointing triumvirate of solemn judges to decide if a tree can stand beside a pool, a cloud drift across a sky.” This is the way the crisis ends—not with a gavel slam but with delay after delay. Problems aren’t solved, but more likely become obsolete and fade as other problems loom up. It made Shulman gag when he tried to protest on this particular occasion at the Court. (p. 29)

Another Kafkaesque example concerns the tall wall of concrete slabs. A friend of Shulman’s was arrested for writing graffiti on it. One of the verses protestors wrote there was “Have we not all a single father? Did not one God create us all? Why does one man betray his brother, to desecrate our fathers’ covenant? Judah has betrayed, and an abomination has been committed in Israel and Jerusalem.” (Malachi 2:10-11) When the writer was arrested, he told the police there is a law allowing verses from the Bible to be inscribed anywhere in Israel. (p. 164) Kafka saw ironies in laws, too.

There are distinctive landscapes and atmospheres, which Shulman brings to life on the page. Some are beautiful, some bleak. The experiences of cold weather in Israel surprised me—I pictured that region as mostly warm. Shulman is a poet, whether writing in Hebrew, translating Telugu, or writing prose in English, and he can describe places, and personalities of fellow activists vividly. The pacifist encounters between the underdog and the people with power on their side are often poignant. The touching moments of appreciation and warm friendship and sharing among the Palestinians and the Israeli supporters are moving.

Shulman describes attempts to protest non-violently, and the settlers’ attacks, and the impatience that develops among youths who begin to throw stones at the police. Even-handedly writing of his observations in a kind of extended journal, he not only describes events, but also reflects on history, human nature, injustices and the non-violent philosophy developed by Gandhi and others. Shulman mentions security officers who are kind and sensitive, little things in daily life.

One of the famous authors who turns up to protest is Amos Oz. The other activists and companions are interesting professional people from Israel, America, Europe, South Africa and elsewhere. (p. 108) These fellow-activists are colorful, from a variety of backgrounds and geographical locations—students, a poet, a longshoreman, an octogenarian (p. 88), an anthropologist from Berkeley (p. 176), a poet/anthropologist from Columbia University, Physicians for Human Rights, Women Who Refuse, etc.

The occasional humor is effective too, bringing out the humanity of Israelis and Palestinians—as when jeering settlers try to insult protestors with knee-jerk accusations, yelling that the Israeli protestors are probably having sex with the Palestinian women. They intended it as a slur and a condemnation—but Shulman comments it was no doubt wishful thinking among the protestors, if only they were so lucky—men after all, are men, and beauty is beauty. Another example comes when a police van door refuses to close so that arrested protestors can be taken to jail—“The Gandhian non-violent resistance” of the van door mechanism finally gave in. (p. 192) There is a strangely moving music made when Palestinians use a fence preventing them from going about their lives freely as a percussive device. (p. 207)

The loneliness of the long-term activist, conscientious and persistent with soulful doubts and uncertainties, which Shulman eloquently expresses, is a specific yet universal experience. The poignant struggle of believers in the non-violent path in Israel is as committed to peaceful solutions as any Satyagraha activity in the world. Doggedly refusing to ignore injustices which feel unconscionable, activists keep working, sometimes wondering how to face a feeling of futility as time goes by.

Shulman confesses he does not believe, as some activists do, that “history” will someday look back and think about what the activists did at this time, and be able to say which actions made a difference. That is not Shulman’s concern. “What is real is this moment, these people, the sliver of moon in the summer sky, the Passiflora tree in the courtyard, the crimson wine, the inevitable sweetness of confusion, the musical murmur of the words, and the profound, ironic happiness of doing what is right in circumstances of rooted, inherent, unresolvable ambiguity.” He says, “There is a past rushing away from us minute by minute…dead voices… in my memory”, and he poignantly voices that insistent whispering: “‘Bind the wounds. Heal the sick. Don’t forget you were slaves. To save one person is to save a world. Don’t be afraid. All that lives is holy. Forgive. Wake up. Shake off the dust and stand up. Feed the hungry. Bring the poor into your home. Cover the naked. Break your chains.’… It is nothing to be right, and a true disaster to be righteous, but it is everything to do what you can”. (p. 212)

Furthermore, Shulman vows to maintain the resistance, to refuse to go along with injustices: “We will meet our foe at every point—every house he demolishes, every olive tree he uproots, every rocky field he is intent on stealing. We will engage him over and over, without violence. We will watch and record and bear witness, and, from time to time, we will stop him. He has guns; we have each other, determination, and some dogged convictions about what it means to be human. That and a certain dark hope.” (p. 212) Shulman refers to various world cultures in his reflections, including the Zen practice of acting for what is right. (p.160)

It is a poignant account, evoking a sense of hope that the story will someday go like the memory of other struggles commemorated by the line “they won the war after losing every battle.” Gandhi wrote that: “In every great cause it is not the number of fighters that count, but it is the quality of which they are made that becomes the deciding factor. The greatest men of the world have always stood alone.” (Oct 10, 1929 Young India, a weekly journal edited by Gandhi, published in Ahmedabad.) It is a crazy gentle wisdom of not resisting evil violently, which in the long term can win. Violence is a linear strategy, which forgets that we live in a non-linear universe. Short-term gains made by violence are not enduring; they breed deep animosity.

Shulman is aware that the machinations of injustice are massive and stubborn. “For now, the settlers will remain in place; for now, the greed, the hate, the killing of innocents with impunity—all this will continue against the constant background screech of the self-righteous. Policemen will do their duty. Soldiers will follow orders, no matter how wrong or foolish their orders may be… There will be the lonely few, on both sides, who refuse to be enemies, who will take any ride for the other’s sake and for the sake of peace.” (p. 220) That following of conscience is enough. The epigraph for the book emphasizes the importance of acting in the moment and seeing the horror of regret: “Hell is realizing that one did not help when one could have.” (James Mawdsley, The Heart Must Break.)

At a protest in Hebron, Shulman contemplated the courage of the young, then reflected—“No heroics, please. We don’t need any more heroes; they are always a huge nuisance. Sometimes they’re positively dangerous—I remember them well from the (first) war in Lebanon.” He celebrates ordinariness: “We’re not so special. Probably everyone here has come, as I have come, for all sorts of wildly obscure, oblique reasons. Out of loyalty to one another, to friends; nothing is worse than the shame of letting them down. Out of a certain insouciant taste for adventure, for something outside the usual routine. Out of anger—the rage at having been lied to by our government for years and years, at having been made silently complicit in their crimes. Out of the need to put oneself to the test. And then—last on the list—out of some kind of inchoate, stubborn moral sense, after all, projected on to the shadow-play screen of politics.” (pp. 215-6) Such honesty shows that he, like the other protestors, is a mensch, an earnest, able human being with heart.

4. The Dialogue Between Hope and Fear

Reading Shulman caused me to remember a tradition from Hasidic stories, about 36 hidden righteous pillars of the world, Tsadikim Nistarim, unknown righteous ones who prevent chaos from overwhelming humanity and causing the world to end. The 36 preserve existence just by their presence on earth. I do not intend to take this symbol of decency too literally—all people of conscience are like the 36. All people sincerely working for peace and goodwill in a world of conflicts may play a role like that—staving off chaos. Shulman’s reflections about carrying on in the face of a stubborn political situation to which even the most optimistic people cannot see a solution on the horizon are helpful. (I heard a joke once: a man asks God when the Israeli Palestinian conflict will finally end, and God responds, “Not in my lifetime.”) We live in a time of psychic numbing forces and events too large and crushing to deal with.

Perhaps the central point of Shulman’s narrative boils down to this: “the horrific struggle to establish a human self results in a self whose humanity is inseparable from that horrific struggle… our endless and impossible journey toward home is in fact our home.” (David Foster Wallace, “Laughing with Kafka,” Harper’s, July, 1998.) The life of the conscience takes many forms—the quiet work of lending a hand harvesting wheat and olives, engaging in non-violent confrontations, reasoning in public talks and letters to officials, among others.

I arrived at the end of Dark Hope reflecting that the life of conscience is its own reward, whether the actions “succeed” or not. To take a stand is always risking the unknown. As the poet Antonio Machado wrote, “Travelers, there are no paths, paths are made by walking.” Shulman’s account and reflections are dramatic illustrations of what Simon Schama says near the end of his documentary series “The Story of the Jews.” There, Schama speaks of an eternal dialogue between “laments and rejoicing, history and hope, earthly world and visionary possibility.” The tension between these sides is always working, always in play. Acts of kindness and simple friendship may not seem as impactful as acts of violence—but that does not mean they are unimportant. Societies are made up of different groups, scholars and merchants, vigorous workers and frail elders. There are some whose work is to be the armed law-enforcers and defenders of citizens’ rights. Some are creative academics and hopeful thinkers. Humanity needs those who are the advance guard of peacemakers. The only way crippling fear and deadly animosities are ever overcome is by acts of hope and kindness. The “eye for an eye” answer to violence is very natural. By instinct those who are violated and afraid naturally seek to strike back in revenge. It’s good if humanity always has some who say no to that, so blindness doesn’t prevail.

EDITOR’S NOTE: William J. Jackson is our Literary Editor. Please consult his author’s page for biographical information, and an index of his previous articles.