Author Archive: Mary Elizabeth King

MARY ELIZABETH KING is professor of peace and conflict studies at the University for Peace and a Rothermere American Institute Fellow at the University of Oxford (UK). She is also distinguished scholar with the American University’s Center for Peacebuilding and Development, in Washington, D.C. She is the author of

The New York Times on Emerging Democracies in Eastern Europe,

A Quiet Revolution: The First Palestinian Intifada and Nonviolent Resistance,

Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.: The Power of Nonviolent Action, and

Freedom Song: A Personal Story of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. During the U.S. civil rights movement, she worked alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. (no relation), in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. She co-authored “Sex and Caste” with Casey Hayden, a 1966 article viewed by historians as tinder for second-wave feminism. For biographical information, more articles, bibliography, et al.

please consult her website.

by Mary Elizabeth King

Nonviolent struggle, also called civil resistance or nonviolent resistance is often misunderstood or goes unrecognized by diplomats, journalists, and pedagogues not trained in the technique of nonviolent action; to them, events ‘just happen’. To the contrary, however, nonviolent struggle requires that practitioners, who take deliberate and sustained action against a power, regime, policy, or system of oppression, consciously reject the use of violence in doing so. The technique of nonviolent action has been employed successfully in diverse conflicts—such as abolition of the trade in human cargo, establishment of trade unions and workers’ rights, voter enfranchisement, colonial rebellions and national independence movements, interstate strife, and religious conflicts—all without resort to violent measures, guerrilla warfare, or armed struggle. Mohandas K. Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. were emboldened by the collective nonviolent action of Africans in Ghana, Kenya, Zambia, and elsewhere, in the nationalist drive for independence. If violence is to be significantly reduced or abandoned in acute conflicts today, a realistic alternative must be presented, accepted, and understood. Contemplated in this article is the need for study, documentation, and teaching of nonviolent strategic action as a technique for securing justice that lends itself to a host of applications. As Gandhi and King learned from the African nonviolent struggles of their times, and relied on observations of African campaigns to improve their sharing of knowledge, so can the rest of today’s world.

Read the rest of this article »

by Nina Koevoets

Nonviolent resistance constitutes an influential idea among idealist social movements and non-Western populations, one that has moved to center stage in recent events in the Middle East. Mary King has spent over 40 years promoting nonviolence through her involvement in the women’s movement, nonviolence studies, and civil action.

Theory Talks: What is, according to you, the central challenge or principal debate in International Relations? And what is your position regarding this challenge, in this debate?

Mary King at the University for Peace; photographer unknown

Mary Elizabeth King: The field of International Relations (IR) is different from Peace and Conflict Studies; it has essentially to do with relationships between states and developed after World War I. In the 1920s, the big debates concerned whether international cooperation was possible, and the diplomatic elite were very different from diplomats today. The roots of Peace and Conflict Studies go back much further. By the late 1800s peace studies already existed in the Scandinavian countries. Studies of industrial strikes in the United States were added by the 1930s, and the field had spread to Europe by the 1940s. Peace and Conflict Studies had firmly cohered by the 1980s, and soon encircled the globe. Broad in spectrum and inherently multi-disciplinary, it is not possible to walk through one portal to enter the field.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mary Elizabeth King

Leymah Gbowee, Liberian activist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate; photographer unknown

One of the most extraordinary nonviolent, transnational movements of the modern age was the women’s suffrage movement of the first two decades of the 20th century. New Zealand first extended the franchise in the late 19th century, after two decades of organizing efforts. As the new century began, women’s suffrage movements gained strength in China, Iran, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Russia, Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), and Vietnam. Another 20 years and women were enfranchised in countries around the world, from Uruguay to Austria, the Netherlands to Turkey, and Germany to the United States. Few if any of those leading the campaigns for the ballot for women would have identified their approach as one of nonviolent action, nor would they have known its philosophical underpinnings or strategic wisdom. Like most who have turned to civil resistance, they did so because it was a direct method not reliant on representatives or agencies and a practical way to oppose an intolerable situation.

What exactly is the link between the rights of women, gender, nonviolent action, and building peace?

The word gender originates with Old French and until recently pertained mainly to linguistic and grammatical practices of classifying words as either masculine, feminine or (in some languages) neuter. The Oxford English Dictionary cites the earliest English usage in 1384. Chaucer used the French spelling gendre in 1398. UNESCO’s Guidelines on Gender-Neutral Language note that a person’s sex is a matter of chromosomes, whereas a person’s gender is a social and historical construction—the result of conditioning. I would further define the “feminist” project as the struggle for women’s emancipation, the insistence that women should be free as human beings to make fundamental choices in their lives.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mary Elizabeth King

Portrait of Gene Sharp; photograph by Conor Doherty; courtesy of the photographer

Six years ago, Brian Martin (Professor of Social Science, University of Wollongong, Australia) wrote in the journal Peace and Change, “Whereas Gandhi was unsystematic in his observations and analyses, [Gene] Sharp is relentlessly thorough. Most distinctively so in his epic work, The Politics of Nonviolent Action, Sharp has had more influence on social activists than any other living theorist.”

I would go further. Gene has in my opinion done more for the building of peace than any person alive. This is because I consider the knowledge of how to fight for justice and social change without a resort to violence to be the most critical and essential component of building peace.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mary Elizabeth King

How does one learn nonviolent resistance? The same way that Martin Luther King Jr. did—by study, reading and interrogating seasoned tutors. King would eventually become the person most responsible for advancing and popularizing Gandhi’s ideas in the United States, by persuading black Americans to adapt the strategies used against British imperialism in India to their own struggles. Yet he was not the first to bring this knowledge from the subcontinent.

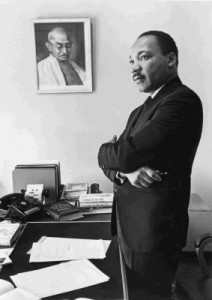

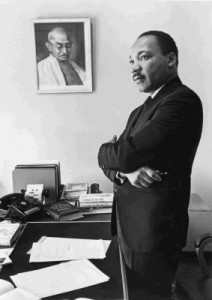

Martin Luther King, Jr. beside a picture of Gandhi; photograph © Bob Fitch

By the 1930s and 1940s, via ocean voyages and propeller airplanes, a constant flow of prominent black leaders was traveling to India. College presidents, professors, pastors and journalists journeyed to India to meet Gandhi and study how to forge mass struggle with nonviolent means. Returning to the United States, they wrote articles, preached, lectured and passed key documents from hand to hand for study by other black leaders. Historian Sudarshan Kapur has shown that the ideas of Gandhi were moving vigorously from India to the United States at that time, and the African American news media reported on the Indian independence struggle. Leaders in the black community talked about a “black Gandhi” for the United States. One woman called it “raising up a prophet,” which Kapur used as the title of his book.

While a student at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, King was intrigued by reading Thoreau and Gandhi, yet had not actually studied Gandhi in depth. A friend, J. Pius Barbour, remembered the young seminarian arguing on behalf of Gandhian methods with a reckoning based on arithmetic—that any minority would be outnumbered if it turned to a policy of violence—rather than on principle.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mary Elizabeth King

Around the time that my book A Quiet Revolution was published in 2007, detailing the Palestinians’ use of nonviolent resistance, I recall that The Atlantic was publishing an article by Jeffrey Goldberg. In it, he asked, “Where are the Palestinian Gandhis and Martin Luther Kings?” — or words to this effect. Upon reading this, the question burned for me. How can historical reality be so ignored, and how can history be told in a way that is so one-sided?

The violent responses to Zionism have been assiduously documented. Yet in archives, newspapers, interviews and conversations, I found numerous uncelebrated Palestinian Gandhis and Kings. Indeed, I identified at least two dozen activist intellectuals who had worked openly for years to change Palestinian political thought — many of whom would be deported, jailed or otherwise compromised by the government of Israel for their efforts. More to the point, the 1987 intifada was only the latest manifestation of a Palestinian tradition of nonviolent resistance that goes back to the 1920s and 1930s. Similar oversights have occurred in the histories of peoples all over the world.

Read the rest of this article »