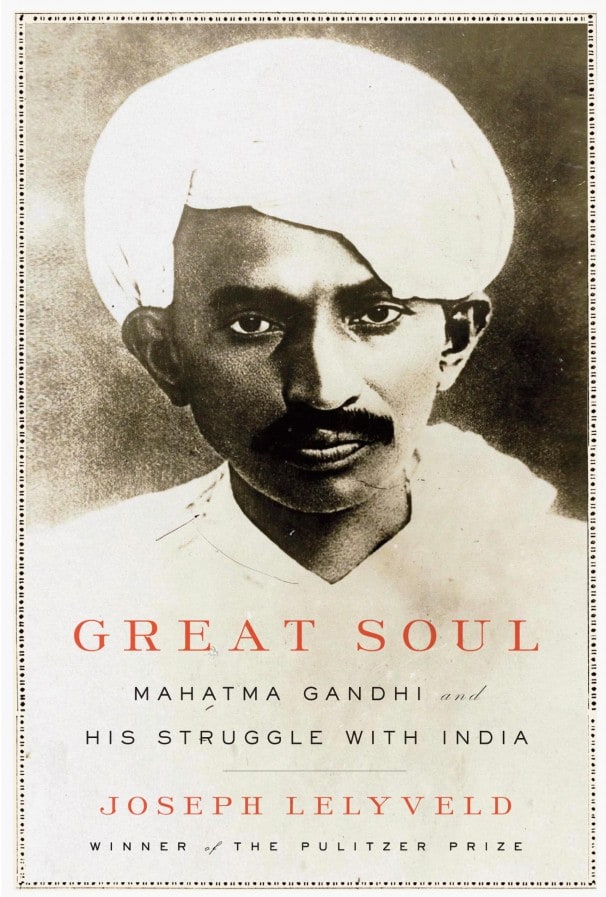

Book Review: Joseph Lelyveld’s Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India

Dustwrapper illustration courtesy Knopf; aaknopf.com

There is an old Indian saying that could very well have been intended for Gandhi: “There’s no one more difficult to live with than a saint.” As portrayed in Joseph Lelyveld’s biography (1) Gandhi was indeed a difficult “saint”, husband, and father. He told his wife and children many times that community came first, and often lived apart from them, sometimes for years on end. His vow of celibacy (brahmacharya), he writes in his Autobiography, was taken in agreement with his wife, after he had already decided on it. When his second son Manilal wanted to marry, as Joseph Lelyveld reports, Gandhi was quite “crotchety” about it, inveighing that he could not “imagine a thing as ugly as the intercourse of man and woman,” not precisely the sort of remark one would hope a father would make to a son anticipating a wedding night. The eldest son, Harilal was unstable, alcoholic, and was accused of embezzling. In the 1930s he converted to Islam, only six months later to reconvert to Hinduism, as if torn between defying or pleasing his father. Gandhi surely must bear some responsibility for his son’s dysfunction.

Gandhi’s attitude towards nonviolence also has its contradictions. If from the beginning of his career as a lawyer in South Africa he was committed to nonviolent resistance, that is, satyagraha, persistence in the truth, he also in South Africa held the rank of lieutenant colonel in the British militia, if as a noncombatant. He famously wrote, “Where there is a choice only between cowardice and violence I would advise violence.” And later he was also to say, “I would risk violence a thousand times rather than the emasculation of a whole race.” Lelyveld questions whether Gandhi’s numerous satyagraha campaigns had any lasting effect. His attempts to change the plight of the untouchables, his efforts to prevent the division of India and violence between Muslims and Hindus, were largely unsuccessful. Many scholars have argued that satyagraha was only one of many factors that led to Indian independence. Was the idea of nonviolence a greater achievement than any result?

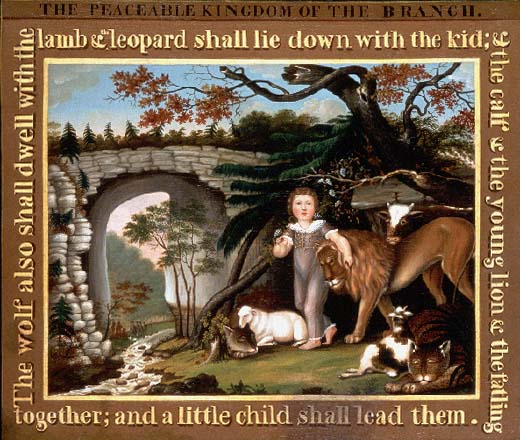

Editorial: Peace Be with You

Edward Hicks painting, c. 1823, from the Peaceable Kingdom series; courtesy Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum.

Peace has been for centuries a universal greeting and sign. We may recall that the World War II military victory V-sign was transformed in the 1960s into a peace symbol; signs of the times. Peace was always more than a simple hello; it was a bestowal of peace on someone, a blessing. In the Middle East, for example, that area of the world so riven by violence, it is perhaps not so strange an irony that a common greeting is (in Hebrew) shalom aleikhem (Peace be with you), and the reply aleikhem shalom (Peace also be with you). In Arabic it is as-sal alaykum (Peace be with you), common to Muslims in Turkey, Indonesia, Central Asia, Iran, India, et al. The response is as-salamu alaykum, and can also be translated as “Peace also be with you”.

Book Review: The Catonsville Nine: A Story of Faith and Resistance in the Vietnam Era by Shawn Francis Peters

The Catonsville Nine protest has often been described as one of the most significant pacifist protests of the Vietnam War era, or, in the words of the actor Martin Sheehan, “arguably the single most powerful antiwar act in American history.” But was it nonviolent, and why should it matter to ask?

All of the Nine were catholic clergymen or laity and took their inspiration, as they said, from the Sermon on the Mount, Vatican Council II, and the recent encyclical of Pope Paul VI, Populorum Progressio (“On the Development of Peoples”). They were grounded in the Christian pacifism of Tolstoy and Dorothy Day, and influenced by the social message and call to action of Liberation Theology.

As Shawn Francis Peters writes in his arresting history, The Catonsville Nine (Oxford University Press, 2012), “They framed their protest as a call to rouse their church from its slumber regarding peace and social justice issues.” And as one of the Nine, Tom Melville declared, “Our church has failed to act officially, and we feel that as individuals we’re going to have to speak out in the name of Catholicism and Christianity.” The protest action was rich in symbols; it resembled a ritual. As they set fire to the nearly 400 draft files with their own homemade napalm, they spoke of the flame as “more than a mechanism for destroying the draft files. It was an enduring Christian symbol that evoked Pentecost.” Daniel Berrigan prayed that the flame would “light up the dark places of the heart, where courage and risk were awaiting a signal, a dawn.”

The Catholic Worker Orchard at Tivoli

Vincent van Gogh, “The Flowering Orchard”; 1888; Metropolitan Museum, New York; courtesy of commons.wikimedia.org

There is a sense of satisfaction in planting a tree. Usually it will be around far longer than the planter. The oak that Shelley planted as a child at his family home became a memorial. People still collect leaves from trees near Tolstoy’s grave, trees that shaded him on his walks through Yasnaya Polyana. There are good reasons for planting trees. Even a Tolstoy had to be reminded of life’s brevity. Planting a tree that will shelter our grandchildren, and theirs, can silence us before a vast and timeless nature, so still, so much more in touch with the timeless than busy people.

Danilo Dolci: Nonviolence in Sicily

In March, 1969, Danilo Dolci was in New York for the publication of his book, The Man Who Plays Alone. Dorothy Day and I had the good fortune of meeting him for an hour and a half, in a quiet corner of the lobby of the famous Algonquin Hotel, along with ten or so others that included Dolci’s biographer, Jerre Mangione, his editor, the journalist and co-founder of Pax, Eileen Egan and various press people.

Dolci was actually born in Sezana, Yugoslavia, under Italian administration at the time of his birth. So, if you were to imagine a small Sicilian type, you would be surprised. He is over six feet tall and solidly built; his eyes dark blue, behind gold-rimmed glasses. He was wearing an inexpensive knit suit and tie, and spoke without gestures. His answers to our questions were short and precise, often only a yes or no; he always looked directly at the questioner, sometimes returned a question with a question, and sometimes made a joke. Dolci has also published a volume of poetry; he uses words carefully and precisely.

Danilo Dolci: The Gandhi of Sicily

A Passion for Sicilians: The World Around Danilo Dolci by Jerre Mangione. New York: William Morrow, 1968.

Danilo Dolci has been dubbed the “Gandhi of Sicily.” Since the mid 1950s he has attracted attention as one of the world’s leading social reformers and nonviolent activists. His methods and thought should have attracted considerable attention in America, where the need for both grassroots planning (pianificazione) and local redevelopment is apparent, although he remains relatively unknown.

Danilo Dolci, c. 1955; photographer unknown; courtesy of wikimedia.org

Who is Dolci? This is the question Mangione’s comprehensive book sets out to answer. Thanks to a Fulbright grant, Mangione was able to spend several months of 1965 in Partinico, living near Dolci, and his Center of Studies. Part journal, part travel diary, part biography, it holds surprises. For example, Dolci is not Sicilian, and is barely Italian. “His Italian father had German and Italian parents; his Slav mother had parents who were German and Slav. This makes him half German, one quarter Slav and one quarter Italian.” Indeed, the town of Sezana, where he was born on June 29, 1924, is part of Yugoslavia; at the time “administered” by Italy. He began his intellectual life reading not the literature of rebellion and revolution but the classics, including the Koran, the Bhagavad Gita, Confucius and the Tao te Ching. He never read Thoreau and read Gandhi only after a French journalist referred to him as the “Gandhi of Sicily.” His first published book was a book of poetry. He studied architecture for four years in Milan but did not take a degree, stopping short a few weeks before graduation.

Danilo Dolci & Cesar Chavez: Nonviolent Land Reform

Original poster; artist unknown; courtesy of gandhijis-talisman.posterous.com

An extraordinary meeting took place October 7 [1969] in New York City, between Danilo Dolci and Cesar Chavez. That two of the most prominent leaders of the nonviolent land reform and resistance movement should meet might afford a glimpse of not only where the movement was, but in what direction it might conceivably go.

The meeting was attended by only a handful of people: Mrs. Coley, who was handling the arrangements for Dolci’s visit; Mark Silverman, head of the grape boycott in New York State; Anne Israel, a supporter of the boycott in whose apartment Chavez was staying; Dorothy Day; the photographer Bob Fitch, and myself. It was to begin at 6:30 P. M., but as Dolci was coming to the meeting directly from the airport, there was the inevitable delay. Chavez had arrived earlier with several co-workers, New York being the latest stop on their national tour. He walks with a slight limp, the result of a bone disease contracted after a fast. As we waited for Dolci, he told us that the recent grape boycott rally in Washington had been very successful. Spirits were high and there was a real determination to work hard and continue. In talking to some of the other boycotters there that evening one had the same impression. Mr. Ortiz, an organizer from Sacramento who will be helping Mark Silverman in New York, said that progress was slow but that everyone was very hopeful.

The Nonviolence of Health & Healing: The Satyagraha Foundation Interview with Dr. Richard Hoofs

“Grow Healthy,” South Berkeley California mural;

by Youth Spirit Artworks; photo by Ariel Messman-Rucker;

courtesy of Street Spirit.

Satyagraha Foundation (SF): In your book, Prescription for Self-Healing (“Zelfgenezing op doktersrecept”) you refer to the ancient Greek, Hippocratic origins of western medicine and the principle, that “the action of healing must avoid harm.” The Gandhian term for nonviolence, ahimsa, can be translated as, “Do no harm”. Can we also speak of ahimsa as a principle for healing?

Richard Hoofs (HOOFS): Absolutely we can apply ahimsa to healing. The first principle for a doctor or health practitioner is not to harm the patient. Every doctor swears an oath to this. The word heal, in fact, comes from the root to make whole, or to become one again, and by this I mean to reconnect with the source, to the light within. To reconnect with this source and light within is a sacred event. It is healing.