by Mohandas K. Gandhi

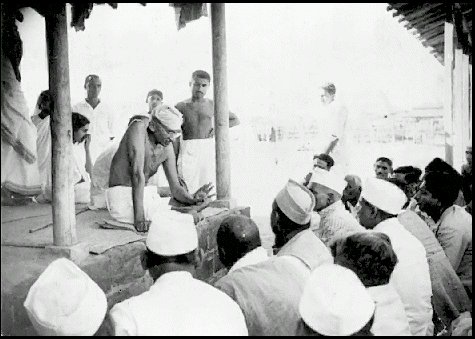

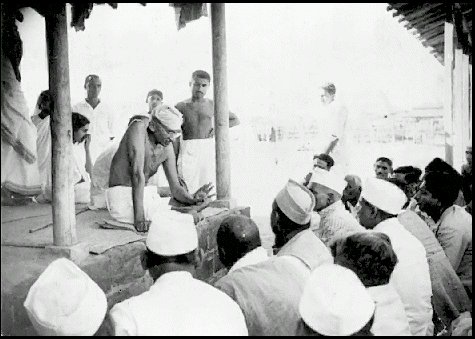

Gandhi teaching his followers; courtesy mkgandhi.org

Editor’s Preface: Gandhi highly valued education as an essential part of his nonviolence program, and insisted it be included in the daily life of the various ashrams that he founded. (1) If regular classes were held for children, adults were also asked to learn spinning, weaving, cloth making, and a host of other skills. It was not until 1909, however, that Gandhi began to systematize his thoughts, in the essay that follows. It is, in fact, Chapter 18 of one of his most important and influential works, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, presented as a series of questions and answers between the fictitious, if sometimes obtuse “Reader”, and answers by a knowing “Editor”, both of whom, needless to say are Gandhi. Hind Swaraj was written in a flurry of work between 13 and 22 November 1909 while Gandhi was on board the Kilnonan Castle sailing back from England to South Africa. Although he continued to write about education in Young India, Indian Opinion, and other of the periodicals he edited, the text that follows is recognized as his first attempt to outline the basics of a curriculum consisting of language, Indian civilization, and ethics. Please consult the notes at the end for further bibliographical information. JG

Reader: In the whole of our discussion, you have not demonstrated the necessity for education; we always complain of its absence among us. We notice a movement for compulsory education in our country. The Maharaja Gaekwar has introduced it in his territories. (2) Every eye is directed towards them. We bless the Maharaja for it. Is all this effort then of no use?

Editor: If we consider our civilization to be the highest, I have regretfully to say that much of the effort you have described is of no use. The motive of the Maharaja and other great leaders who have been working in this direction is perfectly pure. They, therefore, undoubtedly deserve great praise. But we cannot conceal from ourselves the result that is likely to flow from their effort. What is the meaning of education? It simply means knowledge of letters. It is merely an instrument, and an instrument may be well used or abused. The same instrument that may be used to cure a patient may be used to take his life, and so may knowledge of letters. We daily observe that many men abuse it and very few make good use of it; and if this is a correct statement, we have proved that more harm has been done by it than good. (3)

Read the rest of this article »

by Dr. Abhay Bang

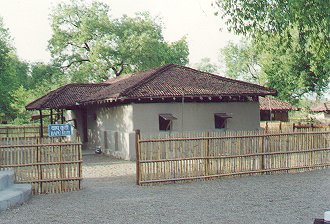

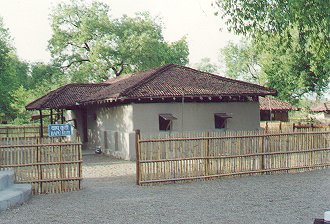

Sevagram Ashram, c. 1960s; courtesy mkgandhi.org

As a child growing up in the 1960s I went to an amazing school. Today, I feel helpless and sad because I’m unable to offer such an education to my son, Anand. “Our childhood was so different. Things have changed beyond recognition,” old timers often moan and groan about the past. Still, my heart is heavy. You may ask what was so different about my school?

From grades four to nine I studied in a school which followed Gandhi’s Basic Education tenets (Nai Taleem), located at Sevagram ashram in Wardha, founded by Gandhi in the 1930s. Education should not be confined within the four walls of the classroom mugging up boring subjects away from Mother Nature. Gandhiji’s Nai Taleem strongly believed that children learnt best by doing socially useful work in the lap of nature. This is how children’s minds would develop and they would imbibe a variety of useful skills. To implement such a system of education, the great poet and Nobel Prize winner, Rabindranath Tagore, at the behest of Gandhiji sent two brilliant teachers to Sevagram. Mr. Aryanakam came all the way from Sri Lanka and Mrs. Asha Devi from Bengal. This duo combined Gandhi’s educational methodology with Tagore’s love for nature and the arts. My parents, followers and friends of Gandhi, were involved with this educational experiment right from the start. The school tried out many novel experiments in education. Here, I will attempt to recall some of these.

Read the rest of this article »

by Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb

Peace mural Shomer Shalom; courtesy shomershalom.org

Author’s Preface: Sami Awad is a Palestinian Christian from Bethlehem, and the nephew of Mubarak Awad, one of the founders of the Palestinian nonviolent movement. [See the interviews we have posted with Mubarak Awad.] When still a boy his uncle gave him the writings of Gandhi, which led to a lifelong commitment to Gandhian nonviolence. Upon finishing his studies in the U.S. he returned to the Palestinian Territories and in 1998 founded The Holy Land Trust, the mission of which is “to create an environment that fosters understanding, healing, transformation, and empowerment of individuals and communities . . . in the Holy Land.” Awad is one of thousands of people in Palestine who resist occupation every day through nonviolent popular resistance. Holy Land Trust works with the Palestinian community at the grassroots and leadership levels in developing nonviolent approaches to Israeli-Palestinian conflict transformation and a future founded on the principles of nonviolence, equality, justice, and peaceful coexistence. Awad has also established the Travel and Encounter Program, which aims to provide tourists and pilgrims with unique religious and political experiences in Palestine, and the Palestine News Network, the first independent press agency in Palestine and a major source of news on life in Palestine today. RLG

Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb: Ahlan wa sahlan, Sami. Nonviolent civilian resistance to foreign occupation has been a way of life in Palestinian society. The words sumud (steadfast) and intifada (shaking off) describe the nature of Palestinian nonviolence. Can you give us a thumbnail sketch of the history of Palestinian nonviolent civilian resistance and the popular struggle?

Read the rest of this article »

by Manmohan Chowdhury

“Nonviolent Political Power”; Jerusalem mural by Banksy; courtesy utne.com

Editor’s Preface: This previously unpublished article, from 1966, continues our re-examination of the influence of Gandhian nonviolence theory on the early European and U.S. peace movements, and is another in our series of rediscovered documents from the War Resisters’ International archive. Please see the notes at the end for further textual and biographical information. Chowdhury is a prescient observer of the political scene and much of what he writes below is as relevant now as when it was written. JG

Political action oriented towards a nonviolent world order should have three objectives: (a) welfare of the masses of the world; (b) elimination of coercion as an instrument of corporate action; that is, as the chief instrument of Government; and (c) drastic revision of the idea of national sovereignty.

Welfare of the people as a whole, even within a single state, is a concept of recent origin in the practice of politics. Traditionally politics has been concerned with struggles for power between powerful individuals and groups who sought power to further their private ends, or interests and objectives that, though not strictly selfish, had little to do with the welfare of the masses. Alexander’s dream of a world empire had a flavour of idealism about it, but the masses were nowhere in the picture.

Read the rest of this article »